Virtue Ethics from First Principles

January 26, 2025 | 2,689 words | 13min read

I’m unhappy with this article. As such, the text needs to be reworked. Please keep this in mind while reading.

In this article, based on the book Nicomachean Ethics by Aristotle and the companion book from Cambridge, I aim to reconstruct the argument for virtue ethics from first principles, meaning from basic axioms, into a single, cohesive argument structure, which I failed to do so.

The central thesis of this article is that by cultivating virtues, one attains a state of eudaimonia, a deep sense of happiness, which is equivalent to being good.

Is There an Ultimate Goal?

The first step is to establish some definitions that will be used in the argument that follows.

Motivational Observation: Every method of production and every type of inquiry, similarly, every action and purpose, seems to aim at some good.

Definition of “good”: We define “good” as “that which is aimed at”; to be good is to be a goal.

- For example, if I trim my fingernails, my goal is to make the nails shorter and orderly. Thus, the good of trimming my nails is that goal.

- Similarly, if I make myself a coffee, my goal is to prepare a coffee that tastes good and serves the function of waking me up. This goal is the good of making coffee.

Definition of “better”: When X and Y are goals, and X is for the sake of Y, then Y is better than X.

- For instance, a carpenter will build a better house than a non, carpenter. Why? Because while building the house, the carpenter performs actions and movements for the sake of the house. They understand the effects of their actions and choose them accordingly. It is because their actions are guided by the goal of the house that the results are better.

Now we can proceed to the argument structure:

Each discipline has a goal (or good) at which it aims.

- (Explanation: Nothing could be called a discipline unless there were some good it reliably sought.)

The higher the discipline, the better its goal (or good).

- (Explanation: This premise follows from the definition of “better.”)

If there is a highest discipline, then it has a goal (or good), which we call the “highest good.”

- (Explanation: This should be understood as the definition of “highest good,” rather than requiring further proof.)

There is a highest discipline.

- (Explanation: Aristotle argues that the highest discipline is “governing/statecraft/politics,” since it directs all other disciplines.)

Conclusion:

- Thus, there is a best goal (or good).

In other words, if a discipline is performed for the sake of another discipline, we call the second discipline “better.” By following this chain of “better” relationships to its final element, we arrive at the good of this ultimate discipline, which we call the “best” or “highest good.”

Goals and Human Actions

The idea that everything has a goal might initially seem controversial, especially if interpreted in a universal, unchanging, and objective sense. However, from a cognitive perspective, this statement holds significant validity.

All actions we take, including our engagement in disciplines, are carried out and interpreted by us as humans. Fundamentally, humans are goal, seeking agents, as understood in the framework of reinforcement learning. Every action we perform has an underlying goal, no matter how trivial it may seem.

You might think that you do something “randomly” or “without a goal,” but this is, by definition, impossible. Every action, even one performed in protest to disprove this point, would still have the goal of protest.

Even reflexes and habits are not performed without a goal; their goals may simply be less immediate or direct. For example, the fight-or-flight response was shaped by evolution with the ultimate goal of ensuring survival.

With this, we have established that there is some kind of ultimate goal, though we have not yet identified what it is or whether we should pursue it.

Criteria of Goodness

Looking back, we defined the highest good as:

“A kind of thing or activity that is acquired or achieved at intervals, with respect to which everything else that one seeks may reasonably be taken as directed, and which one may, in turn, reasonably regard as not directed to anything beyond it.”

To determine what exactly the ultimate good is, we need criteria that characterize it. From our previous argument regarding the ultimate goal, we can identify the following key properties:

Ultimacy: The highest good is that for the sake of which we seek everything else, and it is not itself sought for anything further.

- We can distinguish between different types of goals:

(i) Goals sought only for the sake of something else.

(ii) Goals sought both for their own sake and for the sake of something else.

(iii) Goals sought only for their own sake and not for the sake of anything else. - Goals of type (iii) are at the top of the “for the sake of” hierarchy, making them the highest and most desirable goals.

- We can distinguish between different types of goals:

Self-sufficiency: The highest good is one that implies no further need.

- The intuitive idea of self-sufficiency includes the notion of rest—a state where no further pursuit is necessary and there is an absence of ongoing dependence, meaning one is not constantly chasing after something else.

The Function Argument

Having established the criteria for the highest good, we can now apply the function argument to identify it.

The function argument consists of four distinct steps:

- Establishing that human beings have a function.

- Identifying the human function as rational activity.

- Qualifying that the function is performed well by a good human being.

- Concluding that the ultimate good of a human being is found in virtuous activity.

It is important to clarify that this argument concerning the highest good applies only to humans who meet the following qualifications:

- Chronologically: The person must have lived a sufficiently long life.

- Developmentally: The person must have reached maturity.

With these qualifications in place, we can begin the argument.

Step (i) has already been addressed in the previous section. Aristotle assumes that everything has a function. However, if one remains unconvinced, this idea can also be approached through a cognitive perspective. Humans naturally perceive functions to make sense of the world, for example:

- The function of a plant is to grow.

- The function of a cook is to prepare food.

- The function of a coffee maker is to brew coffee.

Similarly, human beings must also have a function.

For step (ii), we will explore it in the next section of this article.

Step (iii) can be considered through the following argument:

- A good human being—someone who possesses virtues—carries out the human function well.

- To carry out a function well is to achieve what is good for that being.

- Therefore, a good human being attains what is good for them.

In simpler terms, we call something “good” when it performs its function well. For example, a good knife is one that cuts well, whereas a bad knife fails to do so. Similarly, for a person to be good, they must possess the qualities that enable them to fulfill their function effectively.

Parts of the Soul and Virtue

We can now define virtue as follows:

Virtue is that which enables something to perform its function well.

To make this concept more tangible, let’s consider an example. An electric coffee maker has the function of brewing coffee. The virtue of the coffee maker is whatever allows it to brew coffee well. For instance, we might say:

“This excellent coffee maker brews a great cup of coffee because it has the ‘virtue’ one looks for in a coffee maker.”

We can further specify this by analyzing the job of a coffee maker as sending very hot water through ground coffee, which consists of several steps, each of which can be done well or poorly. If the coffee maker performs a particular step very well, such as filtering the water effectively or grinding the coffee beans consistently, then we can say it possesses a virtue related to that step.

However, not every physical part of the coffee maker contributes to its virtue. For example:

- The electrical cord plays no direct role in brewing coffee. A faulty cord does not necessarily make it a bad coffee maker, though it might make it a bad electrical appliance.

- Similarly, if the coffee maker has a scratch or some dust on it, it can still be considered a good coffee maker if it brews coffee well.

Thus, only some parts of the coffee maker contribute to its virtue, while others do not.

Applying This to Humans

We can now apply the same reasoning to humans and ask: What are the relevant parts of a human being for their function?

Upon analysis, we can categorize the human being into three main parts:

- The physical part (the body)

- The higher-level thinking part (rational thought and intellect)

- The lower-level thinking part (instincts, emotions, and desires)

1. The Physical Part

The physical aspects of a human being, while important for survival, do not determine moral goodness. We would not call someone a good person simply because they have a strong heart. For example:

“That crook may be the worst criminal in history, but his heart is as healthy as it can be.”

Similarly, sleeping well at night may contribute to overall well-being, but it does not make someone good in the moral sense.

In other words, the state of the human body does not contribute to the goodness of a human being in a moral or ethical sense.

2. The Higher-Level Thinking Part

The capacity for rational thought—intelligence, logic, and analysis—is another key part of human nature. However, mere intelligence does not determine moral goodness. For example, we can imagine a highly intelligent criminal who uses their intellect for wrongdoing.

Thus, intelligence alone does not equate to being a good person. However, certain aspects of higher-level thinking, such as good judgment, insight, and wisdom, do play a role in moral goodness.

3. The Lower-Level Thinking Part

This aspect of human nature includes emotions, instincts, and impulses. At first glance, we might think that experiencing emotions or having strong instincts does not determine moral goodness. However, the part of our lower nature that listens to and responds to reason is crucial.

For example, imagine a person who lacks self-control—they want to do the right thing but fail to act accordingly. We often describe such situations as if they stem from two conflicting parts within the person. A morally good person should not experience such internal conflict; rather, their desires should align with what they rationally believe to be right.

Overview of Human Parts and Their Corresponding Virtues

Based on this analysis, we can categorize the parts of the human soul and their corresponding virtues as follows:

| Part of the Human Soul | Part of Human Virtue |

|---|---|

| The part that has reason | Thinking-related or ‘‘intellectual’’ virtue |

| The part that lacks reason but can listen and respond to it | Character-related virtue |

| The part that lacks reason and cannot respond to it | Not relevant to moral goodness |

Acquisition of Character-Related Virtue

Now that we know what virtues are, we need to understand how one can acquire them. Aristotle himself did not present the following points as an argument but rather as established facts. I’ve listed them here because I believe they offer interesting insights.

We acquire character-related virtues by performing actions similar to those of people who possess that virtue.

- Just like learning any skill (e.g., playing the guitar), we imitate skilled individuals to learn how to perform effectively. Similarly, we can acquire virtues by observing and mimicking virtuous people.

We acquire character-related virtues not just by performing certain actions, but by performing them in a certain way.

- It is not enough to practice the same easy song over and over in a bad way. If we practice poorly, we will only reinforce bad habits and end up playing the song badly. The same holds true for ethics—if we perform an action poorly, we develop bad habits (vices), but if we perform it well, we cultivate virtue.

Acting well in a given domain initially requires avoiding contrary extremes.

- For example, if one wants to become more courageous, it is unwise to jump into dangerous situations right away. Instead, one should start by avoiding excessive fear or rashness, gradually finding a balanced approach.

There is momentum in action: to the extent that someone acts well or poorly in a given domain, they become more disposed to act in that way.

- If someone lifts heavy weights regularly, they will improve their strength and ability to lift even more. Similarly, by avoiding indulgence, we gradually become more moderate, and once we’ve developed this self-control, it becomes easier to maintain.

When someone regularly performs actions similar to those of people with a particular virtue, and if they genuinely enjoy acting in that way, we can be confident that they possess that virtue.

- The first step in acquiring a virtue is to perform the actions that virtuous people do, according to a set of rules. But the second step is to do so independently of the rules—acting virtuously because one enjoys it, rather than merely following external instructions. When this happens, we can be sure that the virtue has fully developed.

Definition of Character-Related Virtue

We’ve already discussed what virtues are in a general sense, but we haven’t yet provided a formal definition. Let’s remedy that now with a more precise formulation:

Character-related virtue is defined as:

- A state involving deliberative purpose: It is tied to rational decision-making and purposeful action.

- Occupying an intermediate position: Virtue is the balance between extremes, avoiding both excess and deficiency.

- Determined by reason: It is shaped and guided by rational thought.

- As a person with practical wisdom would determine it: The virtuous individual, possessing practical wisdom, determines what is appropriate in any given situation.

Aristotle conceives of a virtue of character in all three of these ways:

- It is a stable trait: Virtue is not a fleeting quality; it is a lasting and dependable characteristic of a person.

- It is developed and established through practice: Like any skill, virtue is built up over time through consistent practice and experience.

- It is analogous to a skill: Just as one practices a skill to improve at it, one develops virtues by repeatedly acting in accordance with them.

The Doctrine of the Mean

The Doctrine of the Mean has two key components:

(i) Each virtue, as a state, is an intermediate position between two vices—one

of excess and one of deficiency.

(ii) Any correctly felt emotion or properly carried out action lies between

those that would go astray due to some excess and those that would go astray due

to some deficiency.

This doctrine can be used both as a classification tool to identify virtues and as a practical rule for guiding behavior.

When understood as a practical rule, it should not be seen as merely a call for moderation. For example, an egregious violation of justice deserves a harsh response, not a moderate one. The Doctrine of the Mean is better understood as offering general advice: it encourages finding balance and avoiding extremes, but it recognizes that some situations may require more than just moderate action.

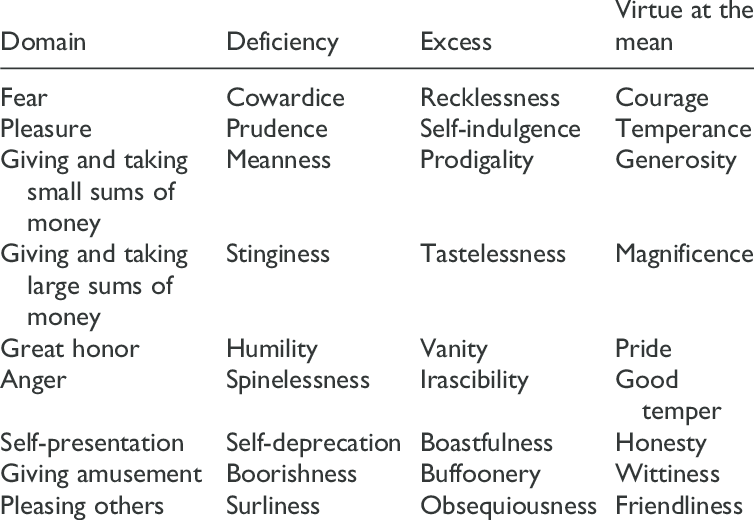

Classification virtues

We can use the Doctrine of the Golden Mean to identify different kinds of virtues, their respective vices, and the “golden mean” between the extremes.

Conclusion

There is much more that is left to be said, but these are some of the essentials of constructing virtue ethics.

One can summarize it as follows:

- Something is good if it fulfills its functions well.

- The properties that make it good are called virtues, and those that make it bad are called vices.

- A human is made up of three parts, each corresponding to different virtues that help the human fulfill its function.

- A human is good if they are virtuous with respect to the identified virtues.

- A good human does good deeds.

- An action is good if it is performed by someone with virtues, follows the practical wisdom required for the situation, adheres to the doctrine of the mean, and is chosen freely.