How to live?

July 13, 2025 | 4,389 words | 21min read

This is an extended version of something I previously wrote. If you’re more interested in the core idea or essence, read Philosophical Ramblings #08: What to Value? instead.

For this article, I used voice dictation and corrected the resulting errors using ChatGPT, so the style may feel a bit different from my other writings.

1. We should only Value Intentions

One central question that has plagued humankind throughout history is: How should we live? What does the best possible life look like; and how must we act to achieve it? In this article, I propose one answer to that question: a way to live the best possible life consistently, without relying on luck, a way of living that is entirely in your control.

There are two caveats I want to note before you read this article.

First, most of the core ideas presented here have already been explored in my previous writings. You can think of this piece more as a synthesis, of them. If something feels underdeveloped or unfamiliar, I encourage you to follow the links throughout the article for deeper context.

Second, when I use the words should or ought, I don’t mean them in the classical moral sense, as something one is obligated to do for its own sake. Instead, I use them in a practical, conditional sense: If one wants to achieve a certain goal, then the action one should take is the action that best fulfills that goal. In this way, should means need. This usage aligns with how Elizabeth Anscombe defines “ought” in her essay Modern Moral Philosophy: as a form of necessity relative to an end goal.

1.1. Meaning and Value Depends on Dasein

The first point is that all meaning and purpose we as humans assign to things is subjective. That means there is no meaning or purpose that is objectively true for all things or for all beings. Instead, meaning, purpose, belief, and value, depends on the concept of Dasein, as formulated by Heidegger.

Dasein refers to the special kind of existence that we human beings have. What is meant by this “special kind” of existence is that we possess certain built-in characteristics that shape how we experience the world.

For example, we humans have two arms, two legs, and move through a three-dimensional space. This bodily structure means that, in general, we assume that when something is in front of us, we can reach out and grab it. That assumption isn’t based on pure logic, it arises from the nature of our embodied existence in the world. So we live in a mode of being where certain beliefs are practically built-in.

For other beings, their mode of existence, their Dasein, is different. A fish, for instance, doesn’t have arms, so it would make no sense for it to “believe” it can reach out and grab something. That belief is simply not available to it, because of its structure and its way of being in the world.

So when I speak of a “mode of existence,” I mean that a being exists in the world with certain physical and experiential structures, and these structures shape what beliefs are even available to it. From this, it follows that what we value and what we find meaningful also stems from this unique mode of being.

1.2. We can change our Beleifs

The second point relates to Doxastic Voluntarism, the view that we can change our beliefs through either direct or indirect means.

Direct belief control refers to moments when we can decide what to believe, especially in cases of uncertainty. For example, if you leave your house in the morning and aren’t sure whether you locked the door, you might simply choose to believe you did, not based on new evidence, but out of practical necessity. In such uncertain situations, belief can sometimes be shaped by will.

However, this kind of control has limits. Try, right now, to believe that the chair you’re sitting on or the floor you’re standing on isn’t real, it seems impossible. In cases like this, we can’t force ourselves to believe differently through direct effort.

But there’s another kind of influence: indirect belief control. This refers to long-term, environmental shaping of belief. For example, if someone changes their social surroundings, their group of friends, the media they consume, the conversations they have, this will often shift their political beliefs over time. A politically neutral person who surrounds themselves with left-leaning influences may gradually adopt left-leaning beliefs.

The same seems to apply to religion. An atheist who starts spending time with religious people, attending church, reading religious books, and listening to spiritual music may gradually become more religious. Whether that change is good or bad is beside the point, the key idea is that beliefs can be shaped through long-term exposure.

“Do not waste time bothering whether you ‘love’ your neighbor; act as if you did. As soon as we do this we find one of the great secrets. When you are behaving as if you loved someone, you will presently come to love him.”

― C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity

This is what is called long-range voluntary control, the idea that we can deliberately change our beliefs by immersing ourselves in specific environments over time. And there’s strong empirical evidence to support this, at least for many kinds of beliefs (though not all).

1.3. The Stoic Principle of Control

The third point comes from the Stoic principle of control, which holds that the only thing entirely within our power is how we respond to things.

Why is this the case? Let’s examine a few external factors.

Take money, for example. To some degree, we can influence how much money we make by pursuing a good career, working hard, or developing certain skills. But now imagine you are born into a poor farming family in a rural region of Africa. In that situation, the chances of acquiring wealth are drastically reduced. In some contexts, achieving financial security may be nearly impossible, regardless of effort.

The same is true of power or even health, and many other external things. Health is partially within our control: you can eat well, exercise, and avoid unhealthy habits. But imagine you’re born with a severe genetic disorder, that’s not something you chose, and there may be very little you can do to change it.

In short, external things are always subject to luck. That’s not to say we have no influence over them, just that they aren’t entirely up to us.

Even things like memory are not guaranteed. You might develop Alzheimer’s later in life and lose access to your past. And your past itself is already written, it cannot be changed, no matter how much you wish it could. The future is also beyond your direct control. It either unfolds as it will, or it doesn’t happen at all. Either way, you cannot fully determine it.

“Life is divided into three parts: what was, what is and what shall be. Of these three periods, the present is short, the future is doubtful and the past alone is certain.”

― Seneca, On the Shortness of Life: Life Is Long if You Know How to Use It

So what is fully within our control?

The Stoics would say: our response to any situation. That is, the thoughts, judgments, and actions that arise from our character.

For example, suppose a friend asks to borrow money from you. You may not have the financial ability to help them, that part may be out of your control. But you still have complete control over how you respond: with kindness, with honesty, with frustration, with indifference, that’s your decision. You could say, “I’m really sorry, I can’t help right now,” or “No, I don’t want to,” or even lash out in anger. But that choice belongs to you alone.

1.4. Pulling It All Together

Let’s recap the argument so far:

- From the first point, we learned that value is not objective, we can’t assign absolute meaning or purpose to things. Instead, all value is grounded in subjective experience.

- From the second point, we learned that to some extent, we can change what we value and believe, especially through long-term, deliberate exposure to certain environments.

- From the third point, we learned that the only thing fully under our control is how we react to the world; our intentions, our judgments, and our character.

From this, a conclusion naturally follows:

If I want to live the best possible life, and who wouldn’t, if they understood what that really means, then I should value something that is entirely within my control. That means not wealth, not fame, not health, not even my memories or future outcomes: but my responses, my intentions, my character.

This leads to a deeper implication: the only thing that should be valued is intention, the ethical, conscious will behind our actions. Outcomes are neutral. Actions themselves, in isolation, do not carry value either. Only the intention behind the action, that is the authentic choice, aligned with one’s values, has real worth.

2. From Valuing Intentions to Valuing Virtue

So far, the argument has led us to the conclusion that we should value intentions, the inner motivation behind our actions, rather than external things like money, power, or even outcomes and actions themselves. This inner focus offers us a kind of sovereignty: intentions are the only part of the moral equation fully within our control.

But this alone doesn’t yet tell us how we should form or act on those intentions. After all, simply valuing intentions doesn’t answer whether those intentions should be kind or cruel, generous or selfish, noble or spiteful.

For example, suppose a friend asks to borrow some money. One possible reaction would be to respond virtuously, with kindness, honesty, and generosity. But another response might be selfish or spiteful: for instance, saying, “No, I don’t want to help you. I’m keeping my money because I’m greedy or don’t like you.”

Both responses still involve valuing intentions over outcomes. The greedy person isn’t making a utilitarian calculation about consequences; they’re acting based on an internal disposition, just as much as the generous person is.

So the question becomes: why should we prefer virtuous intentions over vicious ones?

Here’s the next step in the argument.

2.1. Vice is Inseparable from External Valuation

The first reason to prefer virtue over vice: it’s nearly impossible to be vicious without also valuing external outcomes, which contradicts our earlier conclusion that only intentions should be valued.

Let’s revisit the example where a friend asks to borrow money, and you say, “No, I don’t want to, I’m a selfish person.” On the surface, this seems like an intentional act, but it’s tied to valuing something external, in this case, the money. You’re keeping the money because you view it as more important than helping your friend. That means you’re not just valuing intention; you’re implicitly placing value on an outcome, namely the possession of wealth.

The same goes for other forms of vice. Suppose someone refuses to help their grandmother move groceries because they’re “lazy” or “don’t feel like it.” Again, even that reaction is based on valuing something external, comfort, time, or personal mood. All of these are outcomes, not intentions in the pure sense.

Hence, vice depends on valuing outcomes, which contradicts our foundational claim that only intentions should be valued. So if we want to consistently value only what is within our control, that is our intentions, then we must also shape those intentions toward virtue rather than vice.

2.2 Virtue as Part of Human Nature

Before we can present the second argument for why virtue is preferable to vice, we need to establish a few premises.

2.2.1 Why Value Consistency?

The first guiding intuition is this: it’s better to value in a consistent and stable way rather than in a chaotic and constantly shifting manner. That is, instead of valuing generosity one day and stinginess the next, one should adopt a stable orientation.

To clarify: this doesn’t mean one should never change their mind. Some environmental factors justify changing one’s response, say if your friend asks you for money to buy food versus money to buy a gun to harm others. But all things being equal, if the situation is functionally the same, our values should not shift randomly.

Why adopt this principle of consistency?

- Simplicity: Occam’s Razor suggests that, all else equal, we should prefer simpler systems. It’s easier to adopt a clear, static rule than a complex, dynamic one that changes with every situation.

- Habit formation: Humans are creatures of habit. If we consistently act on a stable principle, we develop habits and habits make moral behavior exponentially easier. Just as a bodybuilder gets better results by repeating a solid routine rather than reinventing the workout every day, so too do we become more virtuous by applying a stable ethical orientation.

2.2.2 Virtue as a Characteristic of Every Action

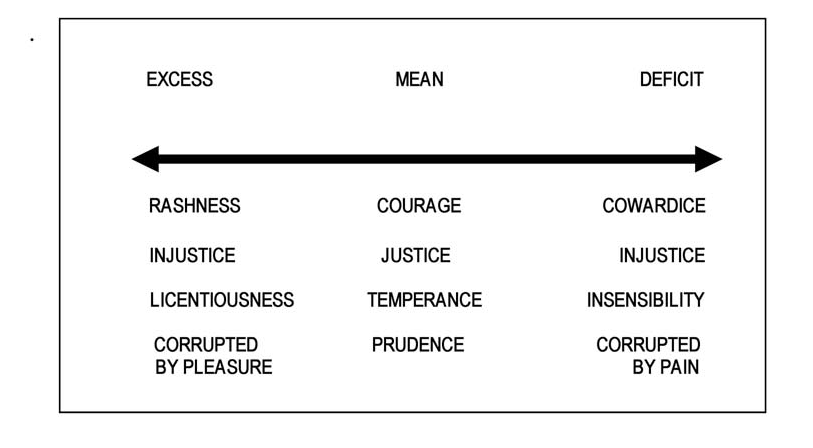

The next point is definitional: every action and reaction we perform lies somewhere on a scale between virtue and vice. This is because virtue, by classical definitions such as Aristotle’s, is the golden mean between two extremes, and vice lies at the extremes.

For instance, suppose a friend asks to borrow money. Your options lie on a spectrum: stinginess on one end, reckless extravagance on the other. Virtue lies in the balanced middle, in choosing wisely based on reason and context. Similarly, if someone asks you afterward how you felt about helping your friend, you again have a spectrum: you might brag about your generosity (pride), downplay it with self-pity, or respond truthfully with modesty. You cannot escape this scale, every reaction lies somewhere on it.

The exact names or labels for virtues and vices may differ across cultures and people, but the structural reality remains: we always act within a spectrum where extremes tend to become vice, and the mean approximates virtue.

2.2.3 Choosing the Golden Mean

With the two previous points in mind, that (1) every action lies on a scale of virtue/vice and (2) consistent habits are easier to maintain, we now face the question: Where on this scale should we position ourselves?

The obvious answer might seem to be: “choose the virtuous mean,” since we tend to associate virtue with goodness. But we can’t just accept this at face value, the entire article has been about building from first principles, not presupposed conclusions.

So why choose the virtuous middle and not one of the extremes?

In short: because virtue is more in line with human nature, or as Heidegger might say, with our mode of being. Practicing virtue aligns with our nature and requires less existential friction than pursuing extremes of vice, which demand more internal conflict and are less sustainable.

A clarification: just because something goes “against” human nature doesn’t make it morally wrong (e.g., opening a beer with a knife instead of a bottle opener isn’t “immoral,” just inefficient). But since we’ve already chosen to value intentions and since that valuation is free for us to define, we should value in such a way that makes practising the intentions the most easiest for us, that is by aligning them with our being.

2.2.4 Human Nature and the Core of Morality

When I say virtue aligns with our mode of existence, I mean that just by being thrown in the world as humans (Geworfenheit): as beings who live, speak and act in the world, certain moral intuitions are built into our condition. Think of what philosopher Donald Davidson called a network of beliefs: we exist embedded in shared language, practices, and expectations. Whether morality was “invented” or not is irrelevant, it is disclosed to us through our being-in-the-world.

C.S. Lewis makes this point vividly:

“Think of a country where people were admired for running away in battle, or where a man felt proud of double-crossing those who were kindest to him… You might just as well try to imagine a country where two and two made five… They have always agreed that you ought not to put yourself first.” — Mere Christianity

Now, I am not claiming there’s an eternal moral law floating in the cosmos, nor that morality is just a cultural invention. Rather, I believe that certain core moral propositions arise naturally from our mode of being. These are not immutable laws, but deeply embedded conditions of human existence, like existing in time or needing communication.

This morality exists in layers, like a matryoshka doll:

- Innermost core: basic moral intuitions we cannot shake off just by being conscious, social creatures.

- Next layer: the specific shape those morals take for humans.

- Next: social and cultural interpretations.

- Outermost: our individual, subjective experience.

This layered view helps us understand why morality can evolve without becoming meaningless, and how different societies can have genuinely different, yet valid moral frameworks, all arising from different ways of being-in-the-world.

Now, consider how we actually change our values or beliefs. As we discussed earlier, long-range voluntary belief change is possible: we can slowly reshape what we believe or value by deliberately exposing ourselves to certain ideas, communities, or habits. However, this doesn’t work for all beliefs. Some are nearly impossible to adopt if they contradict how we are fundamentally structured as human beings.

For instance, you likely can’t make yourself believe the floor beneath you doesn’t exist, no matter how hard you try. Your sensory experience and bodily structure make such a belief unsustainable.

The same seems true for values. It’s far easier to train ourselves to value virtue than to value vice. Why?

Because society, language, and shared practice already reinforce virtue. Traits like honesty, kindness, courage, and fairness are consistently admired. Vice, on the other hand, is more often discouraged, and harder to sustain without conflict, shame, or isolation.

So if we want a value system that is sustainable, and resilient, then virtue aligns better with our human condition, or our “mode of existence,” as Heidegger might say. Vice doesn’t. You can try to train yourself into valuing cruelty, betrayal, or greed, but it will be an uphill battle, one that goes against our embedded moral intuitions and social nature.

Thus, the more deeply a value harmonizes with our existential structure, the easier it is to believe, embody, and sustain over time. This gives virtue not only moral weight but practical viability.

2.3 An Honest Subjective Leap

This entire argument, from valuing intention to valuing virtuous intention, remains a subjective leap. It is not logically necessary; rather, it is an existential choice. One could imagine a person who is consistently malevolent, someone who finds it “easier” to act in selfish or destructive ways. But even then, I would urge such a person to make the leap: to deliberately train themselves toward virtue, as one might train the tastebuds to enjoy spinach despite disliking it.

We choose virtue, not because it is metaphysically mandated, but because it is more deeply human.

3. Objections and Responses

3.1 Clarifying the Role of Externals

One potential confusion must be cleared up. Earlier, I said we should value intentions because they’re independent of external things. But now I seem to say that depending on environmental factors, like your friend’s motivations, might change how we react. Isn’t that relying on externals again?

No. The difference lies in how the external world is used.

When we value external goods like money, success, or power, our happiness becomes unstable, we may or may not acquire these goods, and so our well-being is constantly threatened. But when we value intentions, we retain sovereignty. External factors merely provide the context in which we act, not the source of value.

For instance:

One day, your friend asks for money to pay rent — you judge lending it as virtuous.

Another day, he wants money to buy a gun and commit harm — you judge withholding it as virtuous.

In both cases, you are practicing virtue. You are not reacting based on what you get from the world, but on how you choose to respond to it, based on a stable ethical orientation.

3.2. How can we speak about control in a fully deterministic world?

One clarification I want to make is about what I mean when I say that virtue is “in our control.”

I don’t mean control in the classical metaphysical sense, as in being free to choose otherwise in a given moment. I personally believe the world is fully deterministic: every reaction we have is the result of our prior experiences, our current state, and our knowledge. Given the same inputs, we would always act the same way.

So when I say that we are “in control” of virtue, I mean something more specific, control in the sense that philosopher Harry Frankfurt describes it through the concept of second-order volitions. To illustrate: imagine someone wants to assassinate the president, but unbeknownst to them, a chip is implanted in their brain that would force them to kill the president if they ever decided not to. If this person kills the president because they want to, and not because they are forced, then this reflects their true will. According to Frankfurt, this kind of control, where our higher-order desires align with our actions, is the control I mean. This kind of definition of will or control is explicitly what Heidegger means by Authenticity: the degree to which a person’s actions are congruent with their values and desires, despite external pressures toward social conformity.

Similarly, if someone truly understands the argument I’ve laid out in this article, that intentions (how we react) are the only thing fully within our sphere, and everything external (outcomes, wealth, success) depends partly on luck, then this understanding becomes part of the causal structure shaping their reactions. In other words, knowing this deeply, leads one to live virtuously.

But if instead, you value external things like outcomes or material success, no amount of knowledge can help you consistently achieve your ideal life, because those external things depend on luck and circumstances beyond your sphere of being.

So, when I say virtue is in our control, I mean this: virtue depends entirely on how we react to things, and if we understand this clearly, the life we live depends entirely on ourselves. That is what true control means in this context.

3.3. A Response to the Utilitarian Objection

One objection to the position, of virtue as “life’s goal”, might come from a utilitarian. They might argue: “But acting virtuously often leads to better outcomes! Doesn’t that make outcomes still important?”

My answer is: not necessarily. Virtue is not about the result, it’s about the integrity of the intentions behind an action. Let’s use an example to illustrate this.

Imagine a situation where a button sits in front of a person. If they press the button, 500 people will live. If they do not press it, 500 people will die.

According to utilitarian logic, pressing the button is the clearly better action, more lives saved means more utility. But now, imagine that the person in question has no hands and is bound to a bed. They literally can’t press the button. The outcome, those 500 people dying, still happens.

So: has something “bad” happened to this person?

To a utilitarian: yes, because they value outcomes, even if they’re outside the person’s control. The fact that the person couldn’t press the button doesn’t matter to the utilitarian’s system. Something bad still happened, even though the person had no agency.

But to someone who follows the framework I’ve laid out, where only intentions and reactions are valued, nothing bad has happened. Since the event was outside of their control, and since they had no intention of letting harm occur, their own life and value aren’t diminished. They stayed consistent with valuing only what’s in their power: their intentions.

This is the core flaw in utilitarianism: it ties our value and happiness to external things we cannot fully control. And that makes it a fragile foundation for living a good life.

The Blessed One said, “When touched with a feeling of pain, the uninstructed run-of-the-mill person sorrows, grieves [..] and becomes distraught. So he feels two pains, physical & mental. Just as if they were to shoot a man with an arrow and, right afterward, were to shoot him with another one, so that he would feel the pains of two arrows; in the same way, when touched with a feeling of pain, the uninstructed run-of-the-mill person sorrows [..]

Now, the well-instructed disciple of the noble ones, when touched with a feeling of pain, does not sorrow […] or become distraught. So he feels one pain: physical, but not mental. Just as if they were to shoot a man with an arrow and, right afterward, did not shoot him with another one, so that he would feel the pain of only one arrow.

This is the difference, this the distinction, this the distinguishing factor between the well-instructed disciple of the noble ones and the uninstructed run-of-the-mill person

― Sallatha Sutta: The Arrow, SN 36.6

4. Conclusion: From First Principles to Practice

I didn’t start out saying “external things are bad” or “virtue is good.” Instead, I started from first principles, asking:

“If someone wants to live the best possible life, a life that is consistent, stable, and fully within their own control, then what should they value?”

Again, by “should,” I don’t mean some kind of external moral rule. I mean: given this goal, what is the best strategy to achieve it?

From that question, three core premises followed:

- Value is not objective, it is subjective, and based on our existence as Dasein (Heidegger).

- We can change our beliefs and values, especially over time and through indirect, environmental means (Doxastic Voluntarism).

- Only our intentions are fully under our control, while everything else, outcomes, external things, memories, even our own bodies, are not (Stoicism).

From these three premises, the most consistent way to live a good life is to value only intentions, and to shape those intentions in the direction of virtue, because:

- Virtuous values are easier to adopt and maintain in human society.

- Virtue does not require us to value external things.

- Vice inevitably draws us back into valuing external outcomes, which are fragile and uncontrollable.