Introduction to Poetry

December 25, 2023 | 2,851 words | 14min read

Poetry has long been an mystery to me - Never understood why people like it, never understood the need for analyzing them in school and especially never understood why people treat it so highly. It always felt similar to the esoteric behavior displayed by wine snobs about what the perfect wine is. However, as my interest recently shifted to world building. I began to recognize the potential within poetry as story telling tool, realizing it could serve as integral role to craft religions and history of the world. Moreover, when looking into the history of writing and books than its clear that poetry predates modern novels and as such it’s interesting on it own how this came to be.

With all this in mind, I want to introduce in this text some general concepts about poetry, to help me and you to make more sense of poetry.

What is Poetry?

Defining poetry is as challenging as its counterpart, prose. No single definition can fit the entire body of poetry. But we can make some general claims about it. Generally, poetry is characterized by its greater ambiguity compared to prose and its use of specialized language. The most outward sign of poetry is the unconventional formatting, where text lines don’t span the entire width of a page but wrap around to the next line.

Moreover, poetry employs specialized language that may include newly invented words, “incorrect” grammar, and unconventional sentence structure. Structural techniques such as verses, stanzas, metre, imagery, rhetorical devices and sound patterns are also widely used in poetry. No poem incorporates all of these techniques, poetry often rely on them to achieve a specific impact on the reader.

Contrary to popular belief, poetry is not just about exploring universals truths or deeply personal experiences, but also about day to day life and silly nonsense. One of my favorite example of this is the book “Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats”, in which the author shows the life of cats through the medium of poetry. Here’s a glimpse:

The Rum Tum Tugger is a Curious Cat;

\[...\]

If you offer him pheasant he would rather have grouse.

If you put him in a house he would much prefer a flat,

If you put him in a flat then he’d rather have a house.

If you set him on a mouse then he only wants a rat,

If you set him on a rat then he’d rather chase a mouse.

Yes the Rum Tum Tugger is a Curious Cat—

And there isn’t any call for me to shout it:

For he will do

As he do do

And there’s no doing anything about it!“THE RUM TUM TUGGER” by T.S. Eliot

Pinpointing a precise definition of poetry remains difficult. However, for most individuals, the recognition of poetry is rather intuitive - they know it when they see it.

Poetry Techniques

Metre

Metre describes the arrangement of accents and syllables in the text. In everyday speech, we naturally emphasize different parts of the words we articulate - syllables we emphasize are called stressed, while those not emphasized are called not-stressed For Instance the phrase “And how are you this morning?” most people would stress this phrase like this: “And HOW are YOU this MORning?”, but this is not the only possible option on how to stress this sentence, one could also say “And how ARE you this MORning?”. With this you can already see the way sentence are stressed is not unambiguously.

Various metrical patterns exist, including:

- Accentual Metre: Each line has the same number of stressed syllables, with the total number of syllables varying.

- Syllabic Metre: Each line maintains a consistent number of syllables, though the stressed syllables may differ.

- Accentual-Syllabic Metre: Each line contains an equal number of both stressed and unstressed syllables.

- Free Verse: Characterized by an irregular distribution of syllables and stress,

An example for Accentual Metre is the following poem:

Baa, baa, black* sheep, (4)

Have you any wool? (5)

Yes sir, yes sir, (4)

Three bags full; (3)

One for the mas-ter, (5)

And one for the dame, (5)

And one for the lit-tle boy (7)

Who lives down the lane.“Baa Baa Black Sheep”

In this example here the bold represents stressed syllables and the number of syllables is represented by the number after each line. Accentual Metre is often used in nursery rhymes, rap music also uses a similar scheme.

Pure Syllabic Metre is rare in the English language, one famous form though is Haiku, this is poem form that originated from japan. A Haiku consists of three lines the first lines has five syllables, the second line has seven syllables and the last line has five syllables again. A famous example of a haiku is:

I write, erase, rewrite

Erase again, and then

A poppy blooms.“A Poppy Blooms” by Katsushika Hokusai

This poem was originally written in Japanese and got then translated, that’s why the number of syllables is not correct. Also many modern poets don’t hold themselves strictly to the requirements, it’s more important to fulfill the core idea behind it. I made a try myself to write a haiku:

Basking in the sun

Dread, pain and agony gone

Dreamless sleep!

Often poems are described by the number of syllables a line has, so if every line in a poem has fourteen syllables one would call the poem a fourteen-er, example:

Now the gate has been unlatched, headstones pushed aside;

Corpses shift and offer room, a fate you must abide.“The Gravemind” from the Halo Trilogy

Among various metrical systems, the Accentual-Syllabic metre stands as the most widely used. In this system, the arrangement of stressed and unstressed syllables follow a regular pattern, with each unit of this regularity called a foot.

Common metrical patterns within the Accentual-Syllabic system include:

- Iamb(01): Pronounced as “da-DUM”, this metre has a unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllables. (e.g. return)

- Trochee(10): Pronounced as “DUM-da”, this metre has a stressed syllable followed by a unstressed syllables. (e.g. Garden)

- Dactyl(100): Pronounced as “DUM-da-da”, this metre has a stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables. (e.g. basketball)

- Anapaest(001): Pronounced as “da-da-DUM”, this metre has two unstressed syllables folloed by a stressed syllable.(e.g. contradict)

- Spondee(11): Pronounced as “DUM-DUM”, the spondee features two consecutive stressed syllables.(e.g. bookmark)

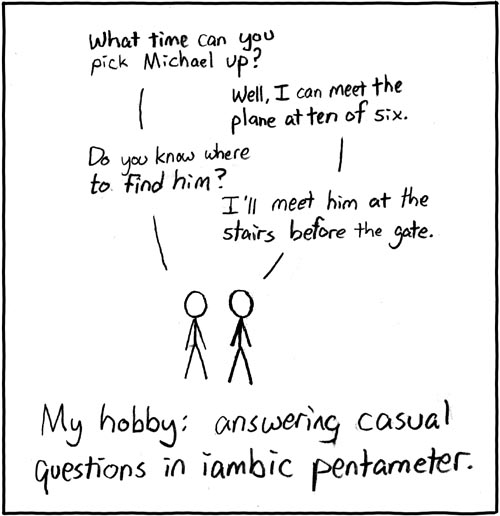

If a poem follows the da-DUM metric pattern we call it iambic, we can combine this property in addition with the number of syllables e.g. a iambic poem with five syllables per line is called iambic pentamter.

The poet Shakespeare, famously often wrote in iambic pattens in his poems.

The Spondee pattern is a pattern that isn’t used throughout the whole poem, but only at certain parts of the poem. This introduced an important facet: metric patterns need not to be the same throughout a poem but can be switched. Using a continuous metre risk monotony and tedium. To counter this poets, often employ a technique called Substitutions, wherein they deliberately alter the metre in the final few syllables of a line. One exmaple if the following iambic poem, the poem introduces trochee and spondee in line 5:

What dire Offence from am’rous Causes springs,

What mighty Contests rise from trivial things,

I sing – this Verse to Caryll, Muse! is due;

This ev’n Belinda may vouchsafe to view:

Slight is the Subject, but not so the Praise,

If She inspire, and He approve my Lays.

(From: Pope, Rape of the Lock, 1-6)

In Line 5, “Slight is” is a trochaic foot that varies from the other monotone iambic pattern. This also indicates to the reader that they should pay extra attention to “Slight”.

Why does this even matter? The significance of metre lies in its ability to evoke specific effects in the reader. For instance, a bouncy metre, can be used to make a poem sound more playful and fun.

Rhythm

All language uses rhythm, poetry especially takes advantage of rhythm to create meaning. Rhythm, in essence describes how the poem flows throughout the text. Metre is part of Rhythm, but Rhythm is more general, it describes the speed of the poem and is influenced by:

- Pauses

- Elisions and expansions

- Vowel and Consonant Length

There are two types of pauses at the end of a line and within a line.

Pauses at the end of a line

Pauses at the end of a line are naturally created in a poem, by the simple fact that the text doesn’t fill the whole text width of the page. Compare for instance the following poems, one written as prose and one properly formatted like a poem:

The sea is calm to-night. The tide is full, the moon lies fair upon the

straits; on the French coast the light gleams and is gone; the cliffs of

England stand, glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay. Come to

the window, sweet is the night air! Only, from the long line of spray

where the sea meets the moon-blanched land, listen! you hear the

grating roar of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling, at their

return, up the high strand, begin, and cease, and then again begin, with

tremulous cadence slow, and bring the eternal note of sadness in.The sea is calm to-night.

The tide is full, the moon lies fair

Upon the straits; on the French coast the light

Gleams and is gone; the cliffs of England stand,

Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay.

Come to the window, sweet is the night air!

Only, from the long line of spray

Where the sea meets the moon-blanched land,

Listen! you hear the grating roar

Of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling,

At their return, up the high strand,

Begin, and cease, and then again begin,

With tremulous cadence slow, and bring

The eternal note of sadness in.“Dover Beach” by Arnold

The poem without any formatting feels a lot faster, because we are missing the short pauses at the end of lines. Also a lot of the Rhythm is lost.

Additionally, we differentiate between end-stopped-lines which are lines that have at the end some kind of punctuation and run-on-lines without any form of punctuation at the end of line. In End-stopped-lines through the punctuation the pauses are especially pronounced.

The Pekes and the Pollicles, everyone knows,

\[...\]

Arc proud and implacable passionate foes,

It is always the same, wherever one goes.

Continued below

While in run-on-lines the pauses are more soft, there is still a short pause due the reader needing to move his eyes from the end of line to the beginning of the next line.

And the Pugs and the Poms, although most people say

That they do not like fighting, yet once in a way,

They will now and again join in to the fray

And they

Bark bark bark bark

Bark bark bark bark

Until you can hear them all over the Park.“OF THE AWEFULL BATTLE OF THE PEKES AND THE FOLLICLES” by T. S. Eliot

Poets strategically utilize these pauses to direct the reader’s focus toward individual words and sounds. This deliberate control over pacing allows poets to imbue additional layers of meaning into their verses.

Pauses within lines

Pauses can also occur within lines, often times they are created by using “-” between lines. Like pauses at the end of lines, they can be used highlight certain words. Additionally they can also be used to break the monotony of a metric pattern and create some contrast within the line.

The time has come,’ the Walrus said,

‘To talk of many things:

Of shoes – and ships – and sealing-wax

Of cabbages – and kings –

And why the sea is boiling hot –

And whether pigs have wings.’“THE WALRUS AND THE CARPENTER” by LEWIS CARROLL

Ellision and Expansion

There are some cases where syllables which are pronounced unstressed are pronounced stressed to fit the metrical pattern, we call this Ellision.

Vowel Length

The speed of poem can be varied throughout a poem, one way to archive that is though the use of different metrical pattern, but this is not the only aspect that influences the speed of a poem another one is vowel length. Example:

The swift, brisk wind kissed the cliffs.

The slow, mellow wind embraced the cliffs.

In line 1, the short vowels (“swift,” “brisk”) lead to a fast and lively pace. In contrast, line 2, with its long vowels (“slow,” “mellow”), imparts a slow and unhurried feeling.

Rhymes

When two words or more sound really similar we call them rhymes. We differentiate between different rhymes form such as full rhmyes where the consonant preceding the last stressed vowel is different: night/delight, power/flower or the rich rhyme when the consonant before the last stressed vowel is also identical: lap/ clap, stick/ecclesiastic. In additon to that there are a variation of other rhymes forms.

Rhymes can appear at different position in a poem. In end-rhyme words at the ends of a line rhyme.

We can also have lines within a line, these are called internal-rhymes. As particular form of this is the leonine rhyme where the middle word rhymes with the word at the end of the line.

Rhymes can be arranged according to different patterns. Some popular rhyme schemes are:

| Name | Form |

|---|---|

| alternate rhyme | abab cdcd … |

| rhyming couplet | aa bb cc … |

| chain rhyme | aba bcb cdc … |

| tail rhyme | aab ccb … |

The same letter are marks for one rhyme. One Example for a alternate rhyme is:

Bid me to weep, and I will weep A

While I have eyes to see B

And having none, yet I will keep A

A heart to weep for thee B

“To Anthea, who may Command him Anything”, by Robert Herrick

Miscellaneous

There are many more techniques poets can employ in their poems, which I don’t and can’t name them all. But a few noteworthy are:

- Alliteration: Is the repetition of the same sound

- The Grumpy Gray Gazelle

- Firefrorefiddle, the Fiend of the Fell.

- Onomatopoeia: words that are associated with a sound

- Boom

- Crash

- Clink

Structure of poems

In this last section I want to take a look at some different popular Poem structures, to be precise the different forms of stanza, which is a sequence of line which form a unit in the poem.

Haiku

The Haiku is a short form poetry that originates from Japan. Traditional Haikus consists out of three lines where the first and the last line have 5 syllables and the middle one has 7 syllables. Besides that Haiku’s are known for having themes about Nature or the Seasons and employing a so called cutting word. Haiku’s don’t use rhyme nor metre, they rely strongly on imagery.

An old silent pond…

A frog jumps into the pond,

splash! Silence again.

by Matsuo Bashō

Limerick

The Limerick is a traditional English verse form. It is often used for humorous poems about nonsense or obscenity. The limerick is written in five-lines, mostly uses anapestic metre and a strict rhyme scheme of AABBAA.

The limerick packs laughs anatomical

Into space that is quite economical.

But the good ones I’ve seen

So seldom are clean

And the clean ones so seldom are comical

by Unknown

Blank Verse

Blank Verse is has a rather simple poem structure written in unrhymed but metered lines, almost always in iambic pentameters.

My lord?

A grave.

He shall not live.

Enough.

by Shakespeare

Ballad

Ballad are often narrative poems, with lines of iambic tetrameter alternated with trimeter. The rhyme scheme is usually abcb.

Down dropped the breeze, the sails dropped down,

‘Twas sad as sad could be;

And we did speak only to break

The silence of the sea!All in a hot and copper sky,

The bloody Sun, at noon,

Right up above the mast did stand,

No bigger than the Moon.

“The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” by Coleridge

Shakespeare Sonnet

Sonnet is a poetic form that originated from Italy. It is lyrical poem of usually fourteen lines in iambic pentameter. The Shakespearean Sonnet usually uses a rhyme pattern of abab cdcd efef gg.

Since brass, nor stone, nor earth, nor boundless sea

But sad mortality o’er-sways their power,

How with this rage shall beauty hold a plea,

Whose action is no stronger than a flower?

O, how shall summer’s honey breath hold out

Against the wreckful siege of battering days,

When rocks impregnable are not so stout,

Nor gates of steel so strong, but Time decays?

O fearful meditation! where, alack,

Shall Time’s best jewel from Time’s chest lie hid?

Or what strong hand can hold his swift foot back?

Or who his spoil of beauty can forbid?

O, none, unless, this miracle have might

That in black ink my love may still shine bright.

“Sonnet 65” by Shakespeare

Conclusion

In this article I gave a short overview about poetry, what poetry is, what techniques it uses and different poem structures. I hope this article helped bring some of you closer to poetry.

References:

- This article is based on a script from Stefanie Lethbridge and Jarmila Mildorf at the university of Tübingen.