Towards LLM-based Software Engineering Agents

September 26, 2024 | 3,990 words | 19min read

I wrote this article back in uni as part of the seminar, “Interactive-Learning”. This seminar was done as a group of two, so not all parts in here are written by me.

1. From LLMs to LLM Agents

The advent of ChatGPT in late 2022 kindled an unprecedented hype in Artificial Intelligence, and specifically Large Language Models (LLMs). Ever since the first version of ChatGPT, which was powered by GPT-3, came out, LLMs have evolved a lot. By 2024, research on LLM agents—LLMs that are enabled to autonomously interact with their environment and perform complex tasks—has emerged as a critical area of investigation. In this report, we want to introduce a special flavor of LLM agents, namely coding agents. Coding agents are, as the name suggests, LLM agents for code generation and software engineering more generally. Analyzing this type of LLM agents is particularly advantageous because the correctness of code can be formally verified. This verifiability simplifies creating high-quality benchmarks.

In this section, we first provide a comprehensive overview of the key developments in LLM research that have led to the current state-of-the-art in coding agents. Next, we will introduce the gold standard benchmark used to evaluate these agents. Finally, we will introduce a few different coding agents and compare and contrast them.

1.1 Large Language Models

Large Language Models are auto-regressive models based on the transformer architecture trained on vast corpora of text data to predict the next token in a sequence. LLMs have demonstrated remarkable zero-shot and few-shot learning capabilities across a wide range of natural language tasks. At their core, LLMs are probabilistic models that estimate \(P(x_t \mid x_1, \dots, x_{t-1})\), where \(x_t\) represents the \(t\)-th token in a sequence. Despite this seemingly simple objective, larger LLMs are said to exhibit emergent behavior, though this remains heavily contested.

The two primary methods for enhancing LLM performance on specific tasks without (fully) retraining are:

- Few-shot prompting / in-context learning: Providing task-specific examples within the context window. This technique leverages the empirically demonstrated ability of LLMs to adapt to new tasks on-the-fly. In the case of few-shot prompting, there is no training necessary at all. This is especially useful when there are not enough computational resources for training of any kind.

- Fine-tuning: Further training the pre-trained model on domain-specific data or particular tasks, often using techniques like PEFT (Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning) to mitigate catastrophic forgetting and reduce computational requirements. This is especially useful as few-shot prompting increases the number of tokens that the attention heads need to attend to, leading to slower inference speed. Thus, fine-tuning is reasonable for minimizing the costs over the long-term.

1.2 Chain-of-Thought

Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting, is a technique that dramatically improves LLMs’ performance on complex reasoning tasks. By prompting the model to articulate intermediate steps, CoT allows the model to reason step-by-step instead of having to directly answer, leading to more accurate final outputs. The underlying reason behind the success of CoT is still unclear.

1.3 Tool Use

While prompting techniques enhance the inherent capabilities of LLMs, integrating external tools expands their functional scope. LLMs famously struggle to do basic arithmetic consistently well, as their training data is natural language, which doesn’t lend itself well to solve mathematical equations. The Toolformer framework, introduced in, demonstrates a straightforward way how LLMs can be trained to use external tools through self-supervised learning. Toolformer employs a two-stage process:

- API-aware data generation: The model is prompted to generate plausible API calls within the text.

- Fine-tuning: The model is trained on this augmented dataset, learning to predict when and how to use tools. This approach allows LLMs to interface with calculators, search engines, file systems, the Python REPL, and other external tools, significantly increasing their problem-solving capabilities and usefulness. An example is depicted in \ref{fig:toolformer}.

1.4 The ReAct Framework

The ReAct (Reason+Act) framework, introduced in, combines reasoning in natural language with decision-making for interactive tasks. ReAct interleaves thought and action steps, where each action returns an observation. This observation is then pasted into the prompt and the process repeats until the LLM believes that it has found an answer. This prompting technique combines tool use and Chain-of-Thought style reasoning in a structured manner.

The ReAct process can be formalized as follows:

- Observation (\(O_t\)): Input from the environment at step \(t\). At \(t=0\), this can be seen as the original Question that the LLM has to answer.

- Thought (\(T_t\)): LLM-generated reasoning based on the observation.

- Action (\(A_t\)): Decision made based on the thought.

- Observation (\(O_{t+1}\)): New input resulting from the action.

ReAct has shown particular promise in tasks requiring both language understanding and interaction with external environments, such as multi-hop question-answering.

1.5 LLM Agents

We have previously referred to the concept of an LLM agent without providing a formal definition. Given the novelty of this research area, there is not yet a universally accepted definition of what precisely constitutes an LLM agent. However, in general terms, an LLM agent can be described as an LLM that is enabled in some way to interact with its environment and that continually prompts itself in a loop until a goal is reached or some other stopping criterion is met, like length of the loop. Usually, the interaction with the environment is implemented via tool-use. In an LLM agent setup, the LLM usually decides itself when the goal is reached and the loop can be exited, such that a final answer can be provided.

LLM agents are often used for tasks that require complex reasoning or planning. Strategies that provide some structure to the prompts of the LLM agent, such as ReAct or Reflexion, are often called agent frameworks.

2. SWE-Bench

With the ever-increasing development of LLMs, it is crucial to have a diverse set of benchmarks to accurately assess their real-world performance. Most high-end models that are released nowadays achieve high scores on the commonly used NLP benchmarks. The HumanEval benchmark is of particular interest, as it focuses on simple, mostly self-contained programming tasks, which can usually be solved writing only a few lines of code with little context required. These tasks are also usually well specified.

| Model | MMLU | HumanEval | DROP |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-4o | 88.7 | 90.2 | 83.4 |

| Claude 3.5 | 88.7 | 92.0 | 87.1 |

| Lamma3 400b | 86.1 | 84.1 | 83.5 |

Percentage of solved task for popular LLM’s on common NLP-Benchmarks.

However, the everyday work of a software developer involves more complex tasks. For example, fixing a bug typically requires navigating through the codebase, opening and inspecting various files to locate the problematic section of code. To more accurately reflect this reality, there is a need for more challenging programming benchmarks. SWE-Bench was created to address this need. In SWE-Bench, instead of solving simple programming tasks, LLMs are required to perform more complex software engineering. Specifically, the LLM’s role in SWE-Bench is to write code for Git pull requests that resolve real-life GitHub issues.

2.1 Construction of SWE-Bench and SWE-Bench-Verified

SWE-Bench was created by collecting pull requests from popular GitHub Python projects. These pull requests were filtered to meet two criteria: (1) they resolve a GitHub issue and (2) they include changes to a test file in the repository, indicating that the user likely added a test to verify that the issue was resolved. After filtering, the collected instances were executed to ensure that at least one test changed from failing to passing as a result of applying the pull request. The result is a benchmark with 2,294 problem instances.

OpenAI then further investigated SWE-Bench and identified several problems:

- Unit tests were overly specific or not relevant to the issue.

- Some issue descriptions were poor and underspecified.

- Some instances were difficult to set up reliably.

To address these issues, OpenAI collaborated with human annotators to rate the severity of these problems and selected the 500 instances with the fewest problems. This resulted in the creation of SWE-Bench-Verified, which is supposed to give more meaningful results.

2.2 Functionality of SWE-Bench

The LLM is provided with a description of a GitHub issue and the entire codebase of the associated repository. The model’s task is to modify the codebase to resolve the given GitHub issue. To accomplish this, the LLM must be equipped with tools to read from and write to the codebase.

Once the LLM has made its changes, a git diff is calculated to create a patch. During evaluation, this patch is applied to the codebase, and if all tests pass, the issue is considered resolved. The final metric for evaluation is the percentage of correctly solved tasks.

3. Retrieval-based Methods

One problem instance of SWE-Bench consists of an issue description and the corresponding codebase in which the issue occurs. Given that the length of these codebases far exceeds the context window size of current LLMs, the first challenge is to select the most relevant context to present to the model. Hence, information retrieval in some form is necessary. In the context of LLMs and LLM agents, the addition of information retrieval in the workflow is referred to as Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG). In SWE-Bench, the authors compare sparse retrieval methods of the BM family with oracle retrieval, where the LLM is given the files that were edited to solve the issue. While these approaches do not seem to be successful, they provide insights into the strengths and weaknesses of current LLMs.

3.1 Sparse Retrieval

Sparse retrieval, as opposed to the more commonly used dense retrieval methods, does not utilize semantic similarity, approximated through cosine similarity in the embedding space. Instead, it uses a statistical approach, where similarity is inherently linked to co-appearance. The Best Matching (BM) family of retrieval algorithms constitute one of the most widely used sparse retrieval methods and are, coincidentally, what was used as a baseline in SWE-Bench.

BM25, the most widely used variant of the BM family, works by estimating the relevance of a document to a query by combining the term frequency (TF) of each term in the query and the inverse document frequency (IDF) of each term across the entire collection of documents. It adjusts for the length of the document, assuming that longer documents may naturally contain more instances of any term. This method allows for efficient and effective retrieval in situations where the context size is large, and a dense, semantic similarity-based approach might be computationally prohibitive or less effective due to domain-specific language, such as programming code.

3.2 Oracle Retrieval

As the ability of an LLM to patch an issue is dependent on the information retrieval to provide the right files that need to be edited, any system that tries to solve SWE-Bench tasks is bottlenecked by the power of the retrieval algorithm. This is problematic as it does not allow for an independent probing of coding ability. To mitigate this, the authors of SWE-Bench also tried an oracle retrieval approach. As the name suggests, the oracle retrieval acts as a perfect retrieval algorithm, providing the code of exactly those files that were edited to solve the issue in the real world. The authors of SWE-Bench note that LLMs with a 27k context window retrieve none of the files from the oracle context almost half the time. This suggests that the localization of the bug is a great source of errors for coding agents.

Naturally, the oracle scenario is much less realistic, as a software engineer does not know a priori which files need to be changed to fix a bug. Hence, one could be lead to believe that the results of the oracle retrieval show the extent to which information retrieval is the bottleneck, or equivalently, how good the LLM is at fixing bugs, when given the code that contains the bug. Instead, in real world scenarios, software engineers have to build up a bigger context. They look at a superset of the oracle retrieved code to be able to reason about how to change the code to not only fix the bug, but also maintain the other functionality that the codebase provides. It is thus unclear whether oracle retrieval is really the upper limit for the information retrieval part of fixing bugs.

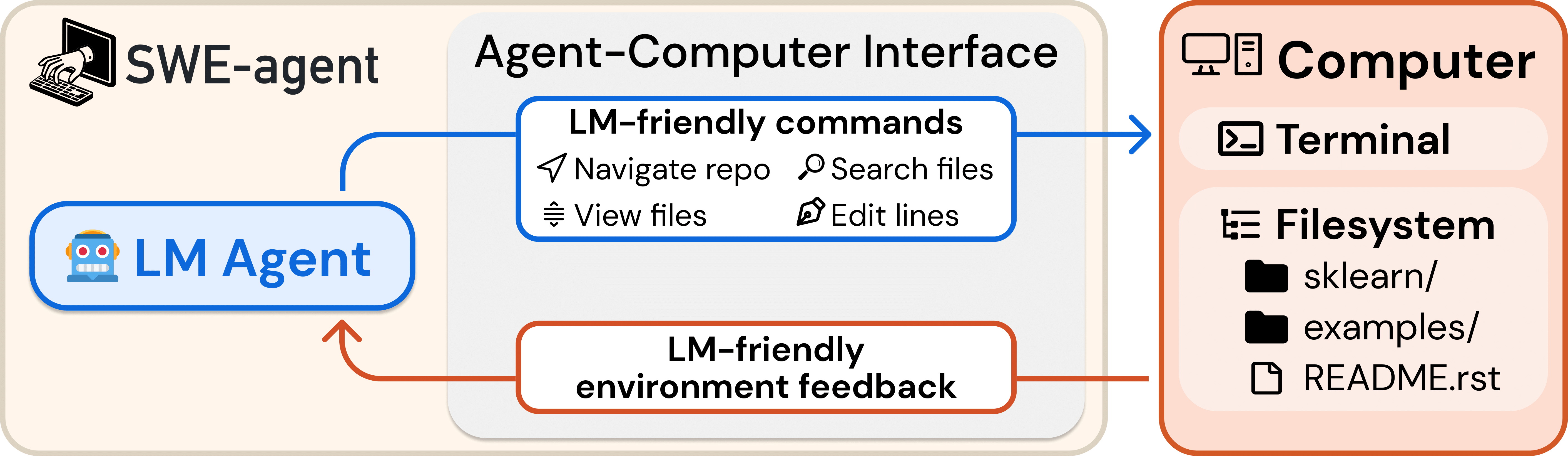

3.3 SWE-Agent

SWE-Agent was the first attempt at solving the SWE-Bench benchmark using an agent. Essentially, it operates within the ReAct framework, interleaving Thought and Action. A key innovation introduced by SWE-Agent is the Agent-Computer Interface (ACI), a dedicated layer that manages all interactions between the agent and the computer. Rather than directly accessing the file system or code, SWE-Agent communicates its actions and intentions using a domain-specific language. This communication is processed by the ACI, which decides whether to execute or deny the agent’s requests based on permission constraints or the correct interpretation of the command.

3.3.1 ACI

The ACI consists of multiple components. These are:

- Search and Navigation Tools: The agent uses specialized commands like

find_file,search_file, andsearch_dirto navigate and search within codebases. These commands are designed to return concise summaries and suppress verbose output to avoid overwhelming the agent with unnecessary details. - File Viewer: Once a file of interest is identified, the agent can utilize the file viewer, which displays up to 100 lines of the file at a time. The agent can scroll through the file using commands such as

scroll_downandscroll_upor directly access a specific line with thegotocommand. This functionality helps the agent efficiently locate and analyze specific sections of code. - File Editor: The file editor allows the agent to make modifications to the code by replacing specified lines. The agent needs to specify the line numbers where a change should be made. The authors of SWE-Agent note that this is one of the most common points of failure, as LLMs really struggle with counting. After editing, the updated content is immediately displayed to the agent, ensuring that changes can be reviewed in real-time. As LLMs struggle with editing files in such a way that the resulting file contains syntactically valid python code, a code linter is utilized to provide feedback on any mistakes detected during the editing process.

- Context Management: To maintain a concise and relevant context, SWE-Agent employs various strategies, such as informative prompts, error messages, and context trimming. The agent is guided to generate both a thought and an action at each step, and any malformed commands trigger error responses that prompt the agent to retry until a valid action is generated.

The design of the ACI is informed by principles derived from human-computer interaction (HCI) studies, emphasizing simplicity, efficiency, and informative feedback to enhance the agent’s performance. For example, commands are kept simple and concise to prevent pollution of the context window, operations are consolidated to minimize the number of actions needed, and feedback is concise yet sufficiently informative to guide the agent effectively. Additionally, guardrails such as syntax checkers are implemented to prevent error propagation and assist the agent in quickly recovering from mistakes. Analysis and ablation studies of SWE-Agent demonstrate that these principles significantly improve performance across various tasks, highlighting the importance of designing ACIs tailored to the unique strengths and limitations of LLM agents.

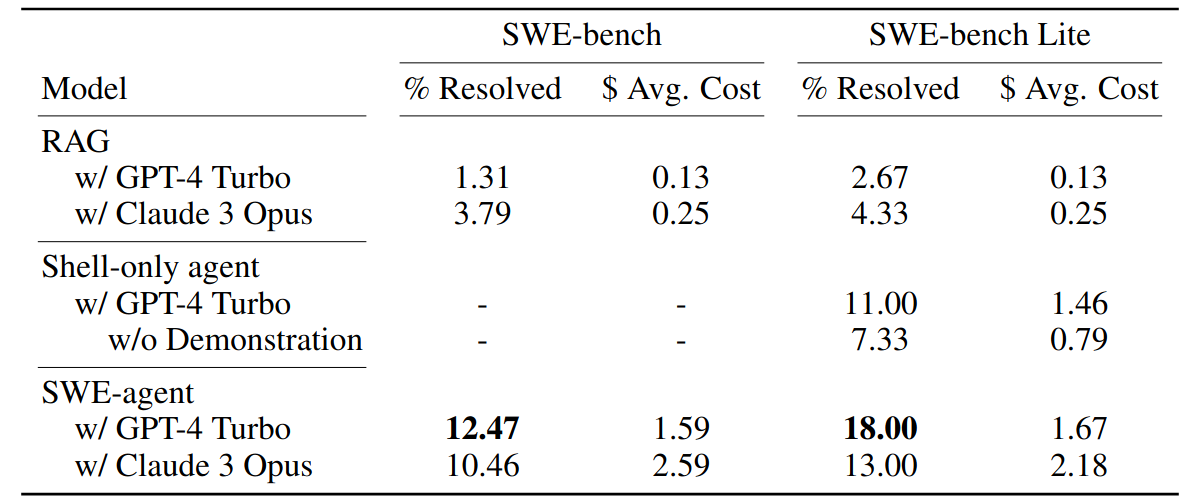

3.3.2 Results

Clearly, it can be seen that SWE-Agent greatly outperforms the retrieval-based methods. The improved results come at a cost, quite literally, as the average cost of one run on one problem instance of the dataset are tenfold compared to the retrieval-based approach. The reason for this is that the retrieval does not occur through some heuristic. Instead, the agent browses different files and makes decisions based on the contexts of the files and the agent’s internal monologue. Thus, there are great inefficiencies whenever a file or even a part of a file is loaded into the context window that the LLM has to look through to judge whether it is needed to solve the issue.

3.4 AutoCodeRover

AutoCodeRover is another automated approach designed to autonomously solve GitHub issues. Unlike other methods, such as SWE-Agent, which treats the codebase as a collection of files, AutoCodeRover represents the codebase using an abstract syntax tree. This structural representation allows for more efficient code search during the iterative process, thereby enhancing the LLM’s understanding of the codebase.

Additionally, AutoCodeRover employs spectrum-based fault localization to improve the LLM’s contextual understanding when tests are available. The authors’ experiments demonstrate that this method successfully solves 19% of the issues in SWE-Bench-Lite, marking an improvement compared to SWE-Agent.

Spectrum-based fault localization aims to identify faulty code segments by analyzing control-flow differences between successful and unsuccessful test cases and assigning a suspiciousness score to the likely problematic areas.

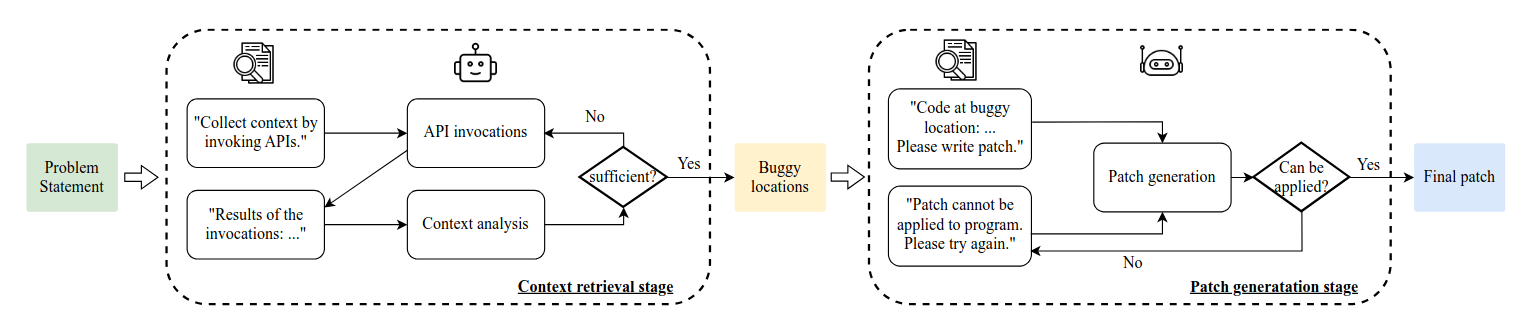

3.4.1 Method

AutoCodeRover takes as input a problem and a codebase. The problem consists of a title and a description in natural language. The codebase must be available offline on the disk. AutoCodeRover operates in two phases: the context-retrieval stage and the patch generation stage.

In the context-retrieval stage, the agent uses various code search tools, to navigate through the codebase and identify sections relevant to the problem. This phase is iterative; at the end of each iteration, the model evaluates whether it has gathered sufficient context or if additional information is needed. If the model determines that it has enough context, it proceeds to the patch generation stage. Otherwise, it remains in the context-retrieval stage and performs another iteration.

A single iteration of the context-retrieval stage operates as follows: First, the model selects a set of tools it wishes to use. These tools are then executed, and their output is returned to the agent. For the evaluation, the agent receives not only the context collected during the context-retrieval stage but also code snippets identified by Spectrum-based Fault Localization, which are likely to contain faulty code. In the patch generation stage, the agent uses the previously retrieved context to generate a software patch in a specific format intended to resolve the issue. If the agent is unable to generate a patch in the correct format, it enters a retry loop, where it attempts a predefined number of times to create a software patch. If after the predefined number of times no patch was created, AutoCodeRover fails the instance.

3.4.2 Evaluation

Experiment Setup The authors evaluate AutoCodeRover on SWE-Bench and SWE-Bench-Lite, which contain 2,294 and 300 GitHub issues, respectively. Additionally, they use Devin and SWE-Agent as baselines to compare their performance with AutoCodeRover. Each experiment is repeated three times to mitigate the randomness inherent to LLMs. The LLM model used is GPT-4, which is responsible both for searching the codebase and generating the final software patch. AutoCodeRover concludes either when a patch is successfully generated or after ten attempts if no patch can be produced.

Results AutoCodeRover achieves an accuracy of 17.60% on the full SWE-Bench with a single pass and 17.96% when running three passes per instance. In comparison, SWE-Agent resolves 12.47% of all GitHub issues in the full SWE-Bench. On SWE-Bench-Lite, the accuracy of AutoCodeRover increases to 19.00% for a single pass per instance, which is expected since SWE-Bench-Lite includes many of the easier instances. This is compared to SWE-Agent, which resolves 18.00% of all instances.

3.5 Agentless

Most methods used to solve SWE-Bench rely on an agent-based approach, including systems like AutoCodeRover and SWE-Agent. These agents perform tasks such as reading and editing files, navigating the codebase and observing feedback. The agent makes multiple attempts, with each attempt consisting of several actions, such as using tools, with each action depending on the previous one.

This approach introduces several challenges:

- Complex and difficult-to-use tools: Tool usage often requires the LLM-generated response to follow a precise format, which can be challenging for an LLM to achieve consistently, especially if the LLM is not fine-tuned on the tool-use.

- Lack of control in planning: In an agent-based approach, the agent autonomously decides the next action based on feedback from the previous one. However, due to the large action space, the LLM can easily become confused.

- Limited ability to self-reflect: LLMs often struggle to differentiate between useful feedback and misleading information, which can lead them down the wrong path.

Agentless addresses these issues by removing the agent-based approach altogether. Instead, it operates in two straightforward phases: identifying the buggy code and repairing it. Specifically, it follows these steps:

- The process begins by taking the existing project codebase and issue description as input.

- The codebase is then transformed into a tree-like structure.

- The LLM ranks the top $N$ most suspicious files that likely require editing to resolve the issue.

- For each of these selected files, the LLM receives a list of class and function declarations and selects those that appear suspicious.

- The full code for the identified suspicious classes and functions is provided to the LLM.

- Using these full code snippets, the LLM makes edits to address the issue. This step is repeated to generate multiple software patches.

- The generated patches are filtered to eliminate syntax errors and test failures.

- Finally, the patches are ranked by the LLM, and the top-ranked patch is chosen as the solution.

None of the techniques used by Agentless in isolation are unique or new. Instead, it cleverly combines them into a simple pipeline for autonomous software engineering, avoiding many of the pitfalls encountered by agent-based approaches through this simplicity.

This methodology allows Agentless to outperform other agent-based techniques, achieving a solve rate of 27.33% on SWE-Bench, compared to 18.00% for SWE-Agent, and 19.00% for AutoCodeRover.

4. Outlook

In this report, we introduced the concept of LLM Agents and specifically talk about their application in a Software Engineering setup. As benchmarks for coding are rather oversaturated and do not depict the depth of software engineering, we introduced SWE-Bench, a benchmark that aims to mitigate the issues that other coding benchmarks are plagued with. We then systematically introduced different LLM Agents that were conceived to solve SWE-Bench specifically and software engineering more broadly. We started with retrieval based methods that are not LLM Agents as they are commonly understood. We saw that they are almost completely incapable of solving SWE Bench. Then, we introduced SWE-Agent and AutoCodeRover, which are truly agentic approaches, that set a new standard for SWE-Bench respectively. Lastly, we took a look at Agentless, a non-agentic approach that provides more structure and is reminiscent of the retrieval-based methods, which currently ranks among the best systems to solve SWE-Bench and is, more specifically, much cheaper than the other approaches.

It remains to be seen whether the future of LLM-based Coding agents will be dominated by more agentic approaches that give the LLM more freedom in decision making or in less agentic approaches that greatly limit the flexibility of the LLM and provide a structure that the LLM is forced to follow. As the capabilities of LLM agents is largely a function of the capabilities of the underlying LLMs, it is expected that LLM agents will get better on their own, without having to change the agent framework. It indicates that, without improved agent frameworks, good results on SWE-Bench will be limited to huge, closed-source LLMs. Research into LLM capability enhancement for software engineering will, thus, be of great importance for companies and users that value data ownership and model sovereignty.