My Methaethical Position

December 26, 2024 | 2,382 words | 12min read

The last time I updated this article was on 05.02.2025. Some of the content I no longer fully agree with, but the last section on My Metaethical Position is still accurate.

Update 21.06.2025: My Metaethical Position still holds, but I have expanded it see Philosophical Ramblings #05: Morality and Intentions .

In a recent post, I discussed metaethics: what it is, the various contemporary metaethical positions that exist today, and how one can categorize them. For a short recap, metaethics is a branch of philosophy that grapples with the question What is morality? — i.e., the ontology, or the study of the essence, of morality. Metaethics is distinct from ethics, which addresses the question What ought one to do? or What is the most moral action one can take? Metaethics, on the other hand, seeks to understand what morality is made of.

This brings me to how one can categorize metaethical positions. For a comprehensive explanation, I recommend my aforementioned article. Broadly, we can differentiate between cognitivist positions, which hold that moral statements are matters of truth, and non-cognitivist positions, which argue that moral statements are not about truth but about something else, such as emotions.

We can further subdivide these categories based on whether one believes that moral values are objective—that is, they exist independently of human minds. Such a stance is called realism. Conversely, the belief that moral values are not objective is referred to as non-realism. While there are additional distinctions that can be made, these are the most significant ones.

Constructivism

With all of this out of the way, we can finally discuss my position on metaethics. I believe that moral statements are cognitivist, meaning they are statements of truth. However, I do not think that morality exists outside of individual minds, whether as a natural or non-natural property, which aligns with an anti-realist position. That said, I do not subscribe to total relativism, such as speaker relativism, which holds that the truth of morality depends entirely on the speaker. Instead, I believe that our morality is constructed at different levels, ranging from small structures like families to the broader society as a whole, also called Constructivism.

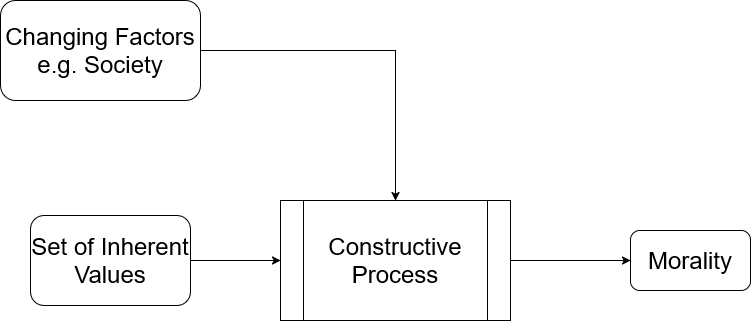

So, what is Constructivism more broadly? Constructivism holds that moral statements are:

- Sentences that are true or false.

- Some statements are true (in contrast with error theory).

- The truth or falsity of the statement arises from a constructive process.

In other words, the correctness of a moral judgment is based on principles determined by a constructive procedure. What this procedure entails varies depending on the specific theory of constructivism one adheres to.

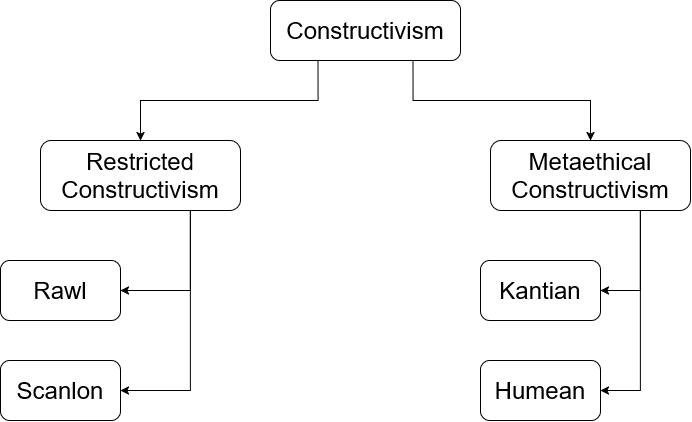

In general, we can differentiate between Restricted constructivists, who argue that only certain aspects of morality are constructed—such as justice. This position can be compatible with various other metaethical positions, including moral realism. On the other hand, we have metaethical constructivism, which argues that morality as a whole is constructed, mostly for practical reasons.

Metaethical constructivism further differentiates between Kantian constructivism, which posits that the morality of all humans will converge through the constructive process, independent of factors like birthplace, and Humean constructivism, which believes that humans are born with certain attitudes and that the constructive process brings out morality from these attitudes, influenced by cultural and societal factors. Importantly, Humean constructivists believe that this process is not convergent, meaning multiple sets of morality can exist simultaneously while still being true.

There are two important questions remaining: first, what is the constructive process, and second, what are the arguments in favor of this position?

I want to start with an illustration of the constructive process. Imagine millions of years ago when the first humans began to appear, or even when we were still primates. There are two groups of people: in the first group, everyone acted egoistically—stealing, lying, murdering, and engaging in all the bad things we would now consider immoral in order to gain an advantage. In the second group, however, people followed certain principles; for example, they adhered to the Golden Rule.

In this world, where humans didn’t yet have sophisticated weapons or knowledge of agriculture, which group is more likely to survive?

I would argue that the second group is more likely to survive. In this group, it is possible to hunt large animals, like mammoths, in cooperation without the fear of being murdered by a fellow human. Murder would violate their principles, leading to the punishment of the attacker, thus ensuring cooperation within the group. This cooperation, I argue, is not possible in the first group, where a constant state of mistrust would prevail.

Thus, there is evolutionary pressure (through the Baldwin effect) for human groups to learn behaviors that we would now call morality.

As such, I argue that the first constructive process that led us to develop a core set of moral principles is evolution. This process has led all humans (or humans that evolved in one place) to share the same set of core moral beliefs. However, I believe this core set is relatively small, only including very general and broad statements. Yet, as humans, we have many more specific moral rules. So, where do these additional rules come from?

For this, I argue that there is a second constructive process, which works at the societal level, based on shared practices and culture. The core set of moral beliefs was sufficient when humans lived in small groups and society was simple. However, as societies became more complex and the number of members in a given society grew (think villages, cities, and nations), the core set of morality was no longer enough. More complex moral rules were required. Thus, moral rules developed in each society based on practical reasons—what worked and what didn’t. How exactly this happened, I am not sure.

These metaethical statements have some important implications that need to be addressed. First, the truth of a moral statement is based on its practical value, meaning there is no objective morality out there. Instead, different societies adopt different rules based on what works. This position is, to some extent, relativistic, but I want to make it very clear that this is only the case at the societal level. In other words, two different societies might have different moral rules that are both true, but within a society, only one set of moral rules is true. Second, when I speak about society, I mean a group of people that have developed together—that is, people with shared cultures and history. Third, these moral values do not have to develop entirely independently within each society. If there was communication between societies, morality could also be exchanged, influencing the moral values of other societies.

Next, I want to go over the arguments for why I believe the metaethical framework I have stated is true. I will only address arguments that I find convincing. For a more complete list of arguments for and against a particular metaethical position, you can read my prior article on metaethics.

I think the strongest argument in favor of my position is that there are large differences in moral rules between societies. For example, in Aztec society, human sacrifice was considered a moral duty, which most Western societies would frown upon. Another example is the difference between Eastern societies like China and Japan, and more Western countries. Eastern societies place much more emphasis on collectivism, such as filial piety, while Western societies focus more on individualism, which also reflects in their moralities. Societies in the Middle East tend to place much more focus on honor. Such differences cannot easily be explained by a realist position.

A non-cognitivist explanation also seems unlikely, because when we use moral statements, we treat them as if they are matters of truth. What is the meaning of language, if not how we use it and what we associate with it? The Frege-Geach Problem, which tells us that Modus Ponens doesn’t work in non-cognitivism, is another issue that non-cognitivists face.

Furthermore, the already mentioned Baldwin effect provides a plausible theory of why morality could develop through evolution via a constructivist process.

Thus, I believe that a cognitivist, anti-realist position, like constructivism, is true.

Lastly, I want to counter some arguments against constructivism. One argument that non-cognitivists often use is the following: if you see someone kick an innocent homeless man on the street, most people would think this is wrong. But where is this wrongness? It is not a cognitive process where we assess logical statements to reach a true conclusion; instead, it is more intuitive and emotional. A counter to this is that we have already done the logical reasoning and assessment beforehand about its truth value, internalized it so well that it is now intuitive knowledge for us.

Another problematic point for constructivism is how to handle disagreements between societies. If there are truly multiple sets of moralities that are all true, how do we resolve conflicts that arise from them? My answer is that we resolve them by showing that your moral system works in practice better than the other. If another society adopts your moral system, you can then work within the same framework and engage in moral arguments. How would one show that one moral system is superior to another? I think a good example of this is how Western liberalism, especially in America, tries to spread democracy around the world by showing other nations the benefits of adopting it.

More on Constructivism

In my previous section, I made the observation: “Different groups have different moral systems.” From this, I concluded that morality cannot be objective. I want to expand on that idea further. A common response to this line of thinking is to assert that morality is not relative, but rather that one group is wrong and another is right. The argument goes that just because two groups have different moral systems, it does not necessarily mean that morality is relative.

I want to counter this. In the prior section, I already mentioned that we can observe societies with radically different moral systems. The radical part is crucial here. If morality were objective, the question arises: how could two groups of people arrive at radically different ideas of what morality is? If there were some “meta-morality” rule underlying these differences, it might explain the divergence, but moral systems vary so widely that this seems implausible. The existence of radical differences suggests a relative moral system. If morality were objective and real, we would expect it to have some observable impact on the world. And if it did, morality should, to some extent, converge over time. Claiming morality is objective while also asserting that it remains non-convergent feels like a contradiction.

One could also claim that morality is objective but has no impact on the world whatsoever. However, this seems even stranger. What is an objective property that has no effect on anything? The idea itself appears contradictory.

Another argument that strongly supports an anti-realist position is the argument from queerness. This argument posits that if morality were a real property, it would be very strange. Morality would need to be a property that intrinsically motivates us to act, independent of our state of mind. Furthermore, if morality were a property of things, we would need some organ or sense to detect it. Since traditional senses like sight or hearing do not detect morality, what would this mysterious organ be?

Fictionalism

Broadly speaking, moral fictionalism is the theory that morality is an invented fiction, akin to the rules of a game or the narrative of a book. When we make moral statements, we can regard them as “true” within the context of this fiction. For example, in the game Risk, every player must take turns in sequence. Is this rule “true”? No, it is an invented fiction for the purpose of the game.

Morality is similar. When we say, “Murder is wrong,” this is an assertion with truth value only within the context of the fiction of morality.

There are many branches of fictionalism. For instance, meta-fictionalism is the thesis that, when making moral statements, the speaker is essentially asserting that, according to a particular fiction, the statement is true.

For example, “Murder is wrong” means, for a meta-fictionalist, something like: “According to the morality fiction, murder is wrong.”

This theory raises several questions, the first being: what is this fiction? Here, constructivist claims about morality fit neatly. Morality, as a fiction, is developed through a constructive process, shaped by mechanisms such as evolution. Why would such a fiction develop? As argued earlier in this article, morality aids group survival by fostering improved cooperation.

One objection to this theory is that it seems absurd to claim that morality is just a fiction. A counterargument is that there is evolutionary and societal pressure to enforce the belief that moral statements are objectively true. If people believed morality was merely a fiction, they might act immorally. Therefore, it is in society’s best interest to pressure individuals into believing morality is objective and real.

My Metaethical Position

I believe that when someone says, “Murder is wrong,” they genuinely believe murder is wrong. However, I argue that what morality actually refers to is a fiction. This fiction was created through a constructive process and is reinforced by societal pressure to ensure people perceive morality as objective and real. This enforcement helps maintain adherence to the moral fiction.

Central to why I believe this is that when we speak about morality, we speak about “What do I owe other people?” But where should this owe come from? Why do I owe you not to kill you? Owing implies having some kind of debt toward another, but where should this debt originate? For theists, the answer is easier—God creates us with this debt. But if you are not a theist, then this explanation doesn’t work.

One way this owe could arise is if we, as a society, agree to have rules imposed upon us—morality as a social contract. In this case, we say, “I owe you not to kill you because we made a contract in which I promised not to kill you.” In this sense, morality is a fiction, just like laws—something we created to ensure societal flourishing and our own survival.

Resources:

- “Fictionalism” Stanford Encylopedia