Nature of God

April 12, 2025 | 5,252 words | 25min read

This article should be read as an intellectual thought experiment, rather than a statement of belief. I think that if one believes in God, non-agentic gods are philosophically less problematic.

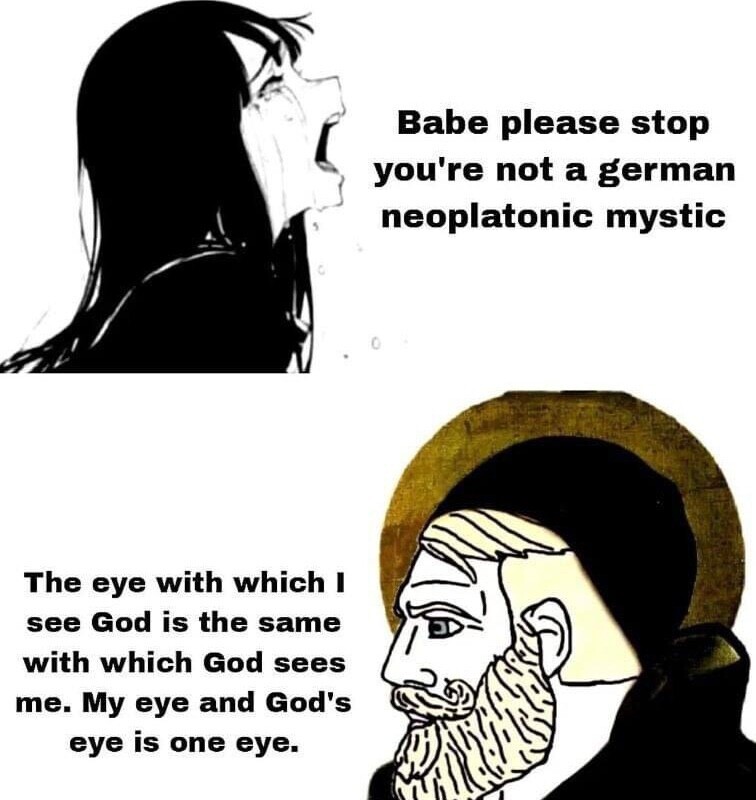

This article is inspired by Neoplatonism, but I have not yet done a deep dive into it. As such, some arguments might be incomplete or could be expressed more elegantly. I will try to revisit this article after I’ve done more reading on the topic.

1. Properties of God

One interesting subfield in both philosophy and theology concerns the ontology of divinity, in other words the essence and the associated characteristics and properties we can ascribe to God.

One common property ascribed to God in most religions, such as Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism, is that of being agentic, i.e. a being that can act upon the world consciously. God has an active role that is not rule-based like a natural law, but instead guided by some form of intelligence.

In addition, theology almost always claims that God is infinitely good, the origin of goodness itself. There are good philosophical reasons for why a god would have these properties, mainly that God is often constructed as the greatest conceivable being, and being the greatest implies the characteristic of being infinitely good. If one subscribes to a telos worldview—where everything has a purpose—then God can be defined as the final, self-justifying cause that everything points to in the causal chain of telos, and thus is what we ultimately desire: the highest good.

Similarly, one can argue for God being omnipotent, able to do anything, and omniscient, aware of everything.

There are more philosophical arguments for thinking that God is goodness itself, but I will leave it at this. Importantly, most modern religions subscribe to this line of thinking.

2. Problems with an Agentic Notion of God

The essence of God being both agentic and boundlessly good presents two issues that need to be accounted for in every theological framework.

2.1 Problem of Evil

The first issue is the problem of evil, which can be casually defined as the question of why evil exists. We can categorize this evil as:

- Moral Evil: Evil that stems from human actions. Examples include murder, theft, and torture.

- Natural Evil: Evil that stems from nature itself. Examples include earthquakes, diseases, and birth defects.

The challenge to the theist is the following: if God is infinitely good, then evil would oppose his very nature. If God is omniscient, he is aware of evil. If God is omnipotent, he has the ability to remedy it. And finally, if God is agentic, he is conscious that evil opposes him and would want in principle to remove that evil. Then why does evil exist?

The theist now has various moves they can make. They might argue that moral evil is necessary for human freedom; that evil exists so humans are motivated to draw closer to God and become virtuous; or that evil is a sin we inherited from Adam and Eve and must atone for. All of these arguments focus on the will of God: foro interno—his innermost desire—is to destroy evil, but foro externo—in the external world—there are factors that prevent him from doing so.

But all of these moves are problematic and can be rebutted. If evil is necessary for human freedom, why does God, who always acts in perfect goodness, still have free will? Or, in the face of widespread and horrific evil, God’s choice to prioritize human freedom may contradict his being infinitely good. Regarding evil producing virtue, it may be that hardship can lead to good character, but not all evil seems to lead to virtue. Some evil appears pointless. There’s also the issue of scale: it’s true that good character can arise from struggle, but this does not require the most extreme forms of evil—lesser forms would suffice. Finally, the idea of inherited sin is in itself repugnant, comparable to slavery, which humanity rightly abolished. A loving God would not make us atone for the sins of our ancestors.

Naturally, the theist may offer counters to these rebuttals, but I hope you can see that the problem of evil cannot be simply dismissed and demands a great deal of metaphysical complexity to account for.

2.2 Problem of Divine Hiddenness

I want to continue with the second issue, which is the problem of divine hiddenness: why does God make his existence less obvious to people seeking him?

A theist might respond to this question in several ways. One common response from Christians is that some people may have hardened their hearts, preventing them from perceiving God’s presence. This hardening could be a subconscious or conscious rejection of God. The theist may also point out that God wants us to have freedom, and revealing Himself would take away our ability to choose.

Both responses raise complications. First, while it may be true that some people have hardened hearts and reject God, it is sufficient for a single person to exist—earnestly seeking God with an open heart—to not perceive God, to undermines the Christian rebuttal. Second, it is true that if God acted like a helicopter parent, watching over us all the time to make sure we are never hurt, it would take away our choices. But most people are not asking for that. Simply revealing Himself once—making His presence known, would for many be enough.

Just like with the problem of evil, theist responses will be offered to the arguments above. But the point is that some explanation must be given.

3. A Non-Agentic Notion of God

There is another conception of divinity, outside of the Western Christianity tradition, which is influenced by Greek doctrines such as Neoplatonism and Stoicism. (One could argue that the Stoic notion of God is agentic to a certain extent, but it is still impersonal, which aligns more closely with what I mean by a non-agentic divinity.)

What do we mean by a non-agentic divinity? It is more like a force or law of nature, a field that underlies the fabric of our reality, much like a gravity field. Importantly, just because God is non-agentic does not mean that it cannot play an active role in nature or in human lives. However, it differs from an agentic notion in the way it participates in our lives: the divinity would still have an active role, but this involvement might behave more like gravity. Rather than being the action of an intelligent being, it would be a rational principle (logos) that permeates the cosmos.

Many arguments, such as the Cosmological argument or the Ontological argument, still apply. We still conceive of divinity as the greatest imaginable being, and thus it would have all the attributes that, for example, the Christian God is proclaimed to have (besides being personal), such as infinite goodness, omnipotence, omniscience, omnipresence, and much more.

3.1 Problem of Evil

Before I continue, I want to introduce the principle of Identity of Indiscernibles, which states: If two things are completely identical in every respect, then they are not two things, but one and the same thing. Or, in a more formalized framing: \(\forall \ P(P(x) \leftrightarrow P(y)) \implies x = y\), with \(P\) being the properties of an object.

P1: If two objects are distinct, there must be at least one property that one has and not the other. P2: If two objects have all the same properties, then there is no property that distinguishes them. P3: There are no properties by which the two objects differ. C: Therefore, the objects are not distinct; they are one and the same object.

Why do we need this principle?

This principle shows that whatever comes from God, whether created actively or passively, is necessarily different from God Himself. In other words, God cannot create something that is completely identical to Him, because if it were truly identical, it would be God, not something separate. Since God is perfect in every possible way, anything that differs from Him must, by that very difference, fall short of His perfection. Therefore, whatever is created by God is, in some sense, less perfect than God. It follows that all created things are necessarily inferior to their creator.

More formally

Argument 1:

P1: According to the Identity of Indiscernibles, if two things share all the same properties, they are not two things but one and the same thing. C1: If God were to create something that shares all of His properties (i.e., something equally perfect), it would be identical to God.

Argument 2:

P1: God is perfect, possessing all perfections to the maximum possible degree. P2: Anything created by God is distinct from God (otherwise it would not be created but God Himself). C1: Therefore, anything created by God must lack at least one property that God has—or possess it to a lesser degree. C2: Therefore, all created things are less perfect than God.

With this framework, we can now answer the question: What is evil?

Evil is the distance between created things and God—between the imperfect and the Perfect. In other words, when God creates anything, it is necessarily less good than God Himself, who is pure and infinite Goodness. This gap, this “less than”, between created goodness and divine goodness is what we call evil.

So, when someone asks, “If God is infinitely good, kind, and loving, why does He allow evil?”—they misunderstand what evil is.

Evil is not something God permits arbitrarily; it is a necessary result of anything being created that is not God. Since nothing created can be identical to God, all creation is necessarily less perfect, and thus contains evil (this assumes that perfect goodness implies perfection in all other properties). It’s also important to note that this has a side effect: humans have free will. Without evil, humans would be forced to act exactly as God does, because every action different from God’s would be less than perfect goodness and thus contain some form of evil. In other words, to eliminate evil, we would need to always act in the most perfect way, which would leave no room for freedom of choice.

The question of evil is thus a closed question. If you understand that goodness is identical to God, then you recognize that anything distinct from God must fall short of it, and that shortfall, which is evil, is a necessary consequence.

To use a metaphor: God is like the peak of a perfect mountain, the highest point of being and goodness. The moment we were created, we were no longer at the top of this mountain. Every action we take leads away from this top. To then ask, “Why am I not at the peak?” while walking downward is to misunderstand the direction entirely.

So, evil is not a mystery to be solved, but a natural consequence of being something other than God. The question “Why is there evil?” is based on a misunderstanding of what evil fundamentally is.

3.2 Problem of Divine Hiddenness

Being non-agentic (not a personal being or an active agent), God’s relationship to the world changes fundamentally. This helps us address the problem of the hardened heart and offers an answer to the question of divine hiddenness.

Since God is impersonal, more like a force of nature than a personal deity, it doesn’t make sense to expect God to reveal Himself to us in a personal, direct way, as is sometimes suggested in religious texts like the Bible. God is not a being who acts with intention or chooses to reveal Himself in personal encounters.

Instead, God reveals Himself through the goodness we encounter in life. Every time you experience beauty—whether it’s hearing a beautiful song, reading a masterfully written story, or tasting something delicious—God is present. These experiences contain the manifestations of God as the ultimate source of all goodness. In this way, we see God’s presence not through personal revelation, but through the beauty and goodness that exist in the world.

Thus, God is not hidden; He is there in everyday life in beauty. People just need to realize that beauty, goodness, and God are one. This is not as controversial as it seems. In the worldview I present, God is imagined more like a force of nature, similar to gravity, and thus we can think of God as the underlying thing behind everything that is beautiful and good (similar to Plato’s Theory of Forms, but with a dynamic form).

3.3 Problem with Non-Agentic Notion of God

There are still some philosophical problems that a non-agentic God brings with Him that need to be further explored.

3.3.1 Passive vs Active Evil

A common objection to the idea of evil as a distance from God is that many forms of evil don’t feel passive or abstract at all. Evils such as extreme pain, torture, or injustice feel intensely real, active, and deeply harmful. If evil is merely a lack or privation of goodness, why does it so often feel like an active force that causes real suffering?

The answer has two parts. First, as previously discussed, the distance between humanity and the divine is what makes free will possible. It is through this free will that moral evil enters the world—because human beings, no longer perfectly aligned with the divine will, often act contrary to what is truly good. So, while defining evil as a “lack of goodness” might seem too passive to account for horrors like torture or rape, these are, in fact, direct consequences of moral imperfection. They are what happens when beings endowed with free will misuse it due to their distance from perfect goodness.

Second, both moral evil and, to an extent, natural evil can still be understood as distortions or absences of the good. This aligns with the classical conception of evil as a deprivation rather than a substance in itself, evil is not its own independent force, but a corruption or failure of something that was meant to be good.

$$ \begin{array}{|c|c|} \hline \textbf{Evil} & \textbf{Distortion or Lack of Good} \\ \hline \text{Illness} & \text{A breakdown of physical or mental well-being} \\ \text{Cruelty} & \text{A distortion of love and compassion} \\ \text{Pain} & \text{The absence or disruption of health and comfort} \\ \text{Injustice} & \text{The absence of fairness or moral order} \\ \text{Alienation} & \text{A lack of connection, unity, or belonging} \\ \hline \end{array} $$This framework also helps us make sense of natural evils—tsunamis, earthquakes, genetic disorders, and so on. These too often feel active and malevolent, even though no human will is involved. But just as humanity was created with the capacity to fall short of perfect goodness, so too was nature created in a state of imperfection. Its flaws and dangers are a consequence of its separation from divine perfection.

3.3.2 Scale and Non-Uniformity of Suffering

Another thing we might question is why evil seems to appear at such a scale and with such non-uniformity. Why does a particular land get hit with an earthquake, or why does a certain child get a horrifying genetic disease while another does not?

This can be explained by first realizing that humans have free will and different levels of capacity for goodness and evil, which are influenced by their experiences, society, and circumstances—factors that are all influenced by the actions of their peers and the humans that came before them. This is then escalated by historical factors and social structures, which are a direct consequence of the free decisions of humans. For example, a population in societies with more unjust government structures can experience more evil. It’s like a chaotic system with humans as the input variables, but their decisions make the system chaotic, so that it is impossible to trace back why or how the current configuration of the distribution of evil is achieved.

A more interesting philosophical question that results from this is why the input variables were decided in such a way in the first place. Why did the “first” humans have evil, as in distance from God, distributed unevenly? I want to address this in the next section.

Before we continue, there’s one last issue to address regarding the uneven and seemingly unfair distribution of evil in the world: Why does it often seem that virtuous people—those closer to God and goodness—experience more suffering than those who are distant from God?

First, it’s important to understand that being close to God does not grant immunity from natural evil, such as earthquakes or disease, nor does it shield one from the harmful actions of others. These external forms of suffering, what we might call external evils, can affect anyone, regardless of their moral or spiritual standing. However, what closeness to God does change is one’s susceptibility to spiritual evil, that is the internal corruption of the will through selfishness, malice, and hatred.

A virtuous person may still endure external suffering, but they are increasingly free from internal torment. This can be interpreted as a soul that is calm, in harmony, and at peace with itself: a deep satisfaction or spiritual tranquility. Their suffering, then, is not a sign of distance from God, but rather a participation in the brokenness of the world.

Imagine a doctor in a war zone. They are surrounded by death, disease, and destruction—immersed in physical evil. Yet morally, they are close to God through compassion, service, and sacrifice. The external situation is evil, but their internal state remains good.

At this point, one might raise the example of a psychopath—someone who can commit horrifying acts and yet appear completely at peace. Doesn’t that undermine the idea that spiritual closeness to God leads to inner peace?

The response to this lies in distinguishing between psychological and spiritual peace. A psychopath may exhibit psychological calm, but this is not the same as spiritual peace. Psychological peace can be thought of as a surface-level ease or emotional stillness, while spiritual peace is deeper, rooted in wisdom, love, and alignment with the divine. The former may lack empathy or moral awareness; the latter cannot exist without them.

We should also remember how we defined evil, not merely as an action, but as a state of being, a condition of separation from God. Actions are manifestations of that inner state; an evil act arises from a soul already turned away from the good. In this light, the true mark of a person’s closeness to God is not whether they suffer, but whether they themselves become a source of suffering for others.

So, just because someone walks with God does not mean they will experience less evil inflicted upon them. Rather, it means they are far less likely to inflict evil on others. Their moral compass, aligned with the divine, prevents them from becoming agents of harm, even if they remain vulnerable to the brokenness of the world around them.

3.3.3 Why Do Things Exist? And Why Are They the Way They Are?

Another question we can ask ourselves is: Why does anything exist at all? Why did God create things, especially when, as we’ve learned so far, everything created necessarily contains some amount of evil? Wouldn’t it be better, more good, if God had not created anything at all?

This kind of explanation is also needed for a theistic picture with an agentic and personal God. In such a worldview, the typical explanation is that God valued our autonomy and free will so much that He was willing to allow a bit of evil in order to provide us with that freedom.

The problem with this line of reasoning is that we imagine God as being infinitely good. If God creates something, He also creates it with some distance from Him, which is evil. So how can something infinitely good create something that contains evil? One counter-argument is that because evil exists, we not only have regular good, but also the good of overcoming evil. For example, death and grief allow us to overcome them, creating a unique form of good. But let’s consider another concrete example: chemotherapy for cancer treatment. Would we really say that it would be better, as in producing more good, for people to go through chemotherapy to beat cancer, rather than cancer not having existed at all? A personal agentic God raises many such questions.

In comparison, there is reasoning for a non-agentic God that is metaphysically much cleaner and more compact. This is the thought of creation emanating outward from God, thus creating our world as we know it. We can also compare it to a sun that naturally radiates outward light.

And all beings, so long as they persist, necessarily, due to the power present in them, produce from their own substantiality a real, though dependent, existent around themselves.

Fire produces the heat that comes from it, and snow does not only hold its coldness inside itself. Perfumes especially witness to this, for so long as they exist, something flows from them around them, the existence of which a bystander enjoys.

Further, all things, as soon as they are perfected, generate. That which is always perfect always generates something everlasting, and it generates something inferior to itself.

~ Enneads 5.1(10)§5.1.6.

Why is that the case?

We can borrow the same argument structure used for the Ontological Argument (which is not uncontroversial). If God were not able to produce goodness, then we could conceive of a being that has all the same attributes as God, but with the additional property of being able to produce goodness. This being would then be greater in this property, but this cannot be the case because we defined God as the greatest of all beings in all properties. Alternatively, one can take the following as an axiom—a statement of fact, a priori: “That which is perfect and full tends to overflow.”

More formally

Let \( G \) be a being of maximal intrinsic goodness—i.e., a being than which no greater can be conceived.

For a being to be maximally good, it must possess all qualities that contribute to or embody intrinsic goodness.

Suppose \( G \) does not produce any additional goodness beyond itself.

Then we can conceive of a being \( G′ \), identical to \( G \) in intrinsic qualities, but which also produces additional goodness (e.g., creates good things).

The capacity to produce goodness is itself a form of intrinsic excellence, thus \( G′ \) is intrinsically greater than \( G \).

But this contradicts the definition of \( G \) as the greatest conceivable being.

Therefore, \( G \) must include within its intrinsic nature the property of being a producer of goodness.

So, the answer to the question of why things exist is that God is so full of goodness that He overflows, like a barrel full of water pressing out water at the top, and this overflowing of goodness creates the world.

As a Response To Critique on Plato

The concept of God emanating outward and producing our world comes from Neoplatonism. It can also be seen as a response to critiques of Plato’s theory of forms.

Plato’s theory of forms tells us that there are universals and particulars. Universals are abstractions from particulars—patterns or archetypes. One can imagine this with an analogy: making Christmas cookies. To make them, we take a cookie cutter and press it into dough. This gives us dough in a specific shape, and we then only need to bake it to get our cookie. In this analogy, the cookie cutter is the universal, while the many cookies we produce with it are the particulars. The universal determines the form, shape, and properties of each particular.

So, for all objects in the world—for example, the many different apples, we have one universal “Form of Apple,” which is unchanging and eternal, representing the perfect essence of what an apple is. Similarly, there are Forms of Goodness, Beauty, Chairs, Trees, Humans, and so on. This position is also called Platonic realism, which stands in contrast to nominalism.

One problem for the realist is this: we now have all these forms, but where are they? Why do they exist? Where did they come from?

Neoplatonism offers a solution to the realist’s problem: where the Forms come from and why they exist. It begins with the One, the ultimate source beyond being and thought. From the One emanates the Intellect (or Nous), which contains all the Forms—eternal archetypes of all things.

The process continues as the Intellect overflows, producing the Soul and, eventually, the material world. Everything: apples, trees, humans—derives from this chain of emanation. Each thing in the world reflects the Forms within the Intellect, which in turn reflect the unity of the One.

Thus, Neoplatonism explains the origin and presence of universals(also called “Ideas”) as part of a structured, hierarchical reality that flows from the divine source.

Often he calls Being and the Intellect “Idea”, which shows that Plato understood that the Intellect comes from the Good, and the Soul comes from the Intellect.

~ Enneads 5.1(10)§5.1.8

You might be confused when you remember back to a prior section where I used the act of creation as a criticism towards a personal God, arguing that an all-loving God would not create things knowing that this would produce evil. Since the non-agentic God is still defined as the greatest being, He too should be all-loving and be effected by the same criticism. Importantly, this criticism does not work for a non-agentic God, as this is impersonal, more like a force of nature. It doesn’t consciously create creation because it chooses to do so; instead, creation happens as a natural process of overflowing.

I want to take one point from the prior section that connects neatly with the question, “Why are things the way they are and not different?” That point is: Why were the first things in creation created with different levels of distance from God?

First, we already acknowledged that we can treat creation or the universe as a chaotic system, whose current state is highly dependent on the conditions at the start of the system. Second, the process of emanation does not necessitate uniformity or symmetry. Third, even from very simple, basic rules, near randomness can be achieved. My favorite example of this is that we can simulate random walks using very basic rules in cellular automata.

3.3.4 Desire to Return to God

Another thing that can be criticized is the desire to return to God. If God is the ultimate good, why do so many people not seem to desire to move closer to Him?

This kind of criticism is very effective against personal gods like the Christian God, but to a far lesser extent against to the impersonal God, I have described so far. Goodness is very closely linked with the concepts of love and beauty. We can imagine love as the human desire to attain goodness and happiness, and this goodness and happiness is outwardly represented by beauty.

Thus the answer, to the question at the beginning of this section, is very similar to the answer in the previous section on the problem of divine hiddenness. The desire to return to God, and with that, to goodness itself, is present in every human being but expresses itself differently. Some people access this desire through art, some through music, others through nature, and some through virtue. This is possible because what we perceive as beauty is, in reality, an expression of the goodness in all these activities. Our desire to get lost in these activities represents our desire to return to the ultimate goodness. However, the beauty in our world is imperfect, and that is why we are never fully satisfied with beauty; we always want to see, hear, and experience more.

3.3.5 Omnipotence

One last thing I want to mention is the concept of omnipotence, the property that God can do anything. A question that arises regarding the problem of evil is this: If evil emerges not because God directly creates it, but because the farther something is from the One (or the source of all being), the less it reflects the perfect goodness and unity of the divine source. Then this means that God cannot create a world entirely without evil, because creation necessitates some degree of imperfection. Wouldn’t this dispute God’s omnipotence?

One way to reconcile this is by denying God’s omnipotence. Strictly speaking, the God constructed so far only needs to be infinite goodness for the philosophical arguments to work. However, in addition to this, God must possess all qualities that contribute to or embody intrinsic goodness. Whether omnipotence is one of these qualities is now a matter of debate. Though the idea of a God who is not omnipotent might seem strange at first, it’s not as far-fetched as it may appear. Remember, we conceptualize God as a force of nature, more akin to a gravitational field that unconsciously influences the world, rather than a personal God who consciously acts. In this view, it makes sense that one force cannot do everything.

There’s also another way to think about omnipotence. Instead of imagining it as being able to do anything possible, it may be more accurate to define omnipotence as the ability to do all things that are logically possible. In other words, God can create the world, but He cannot create a rock so heavy that He cannot lift it. Similarly, evil is a logical necessity, and therefore, cannot be avoided in the process of creation.

However, there is a problem with this view. The concept of God is so philosophically appealing because it allows us to ground all of metaphysics in Him as the end of a causal chain, preventing an infinite regress. But if it’s impossible for God to create certain things, it seems that something exists outside of God’s purview. In this case, logic would seem to be stronger than God. This raises the question: If logic is more foundational than God, then this undermines the idea of God itself.

A common rebuttal to the idea that God is bound by logic misunderstands the relationship between God and logic. Instead, logic is not something created by God through conscious decision, but rather something that emanates naturally from His goodness. God’s nature is the source of all logic, and logic flows from Him as a necessary aspect of His perfection. To say God could change logic implies a change in His essence, which is impossible since God is immutable.

Asking whether logic applies to God is a category mistake, much like asking if the number two is blue. Logic, as a human construct, doesn’t apply to God in the same way it applies to the created world. God is the necessary condition for logic’s existence, not constrained by it. Therefore, God is beyond logic, and the question itself misapplies human concepts to the divine.

4. Conclusion

There is alot that I have left out; any arguments that I provided in this article have numerous citicism and numerous rebuttals to them, and then rebuttals of the rebtuals and so on. But I hope I’ve made it clear that there is another way of thinking about god besides the agentic and personnel that is so familiar to us.