What is morality? An Overview of the Metaethical Landscape

November 30, 2024 | 9,664 words | 46min read

I have only recently started exploring philosophy, so keep in mind that I might have gotten some things wrong. Please take everything written here with a grain of salt.

To Moralize or Not to Moralize: Is That the Question?

There are many theories about what actions are morally right or wrong. For example, utilitarianism prescribes that the moral action is the one that minimizes suffering or maximizes the happiness of all parties involved. Deontology, on the other hand, argues that a set of rules defines what actions are right and wrong. For instance, many Christians fall into this camp through Divine Command Theory. Lastly, I want to mention virtue ethics, arguably one of the oldest moral theories. This approach, represented by ancient Greek philosophers such as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, asserts that an action is moral if it embodies virtues—i.e., a virtuous person performs virtuous actions.

However, these theories (aside from Divine Command Theory) do not address where morality comes from or what morality fundamentally is. Instead, they focus on what one ought to do when faced with a moral question.

While the question of how one ought to act is undoubtedly relevant to our daily lives, it does not provide the complete picture of morality in its divine and infinite form. Only by investigating the origins and nature of morality can one truly appreciate its beauty.

Before I begin, I want to reiterate that the questions How should one act?, What is morality?, and Where does morality come from? are all distinct. Although answers to the latter two questions might inform the first, they remain separate issues.

In this article, I will attempt to provide an overview of the question What is morality?

What the Hell is Metaethics?

I’ve already mentioned the question I aim to answer, but which branch of philosophy does this question belong to?

The question What is morality? is primarily addressed by Metaethics. The term “metaethics” consists of the prefix meta, which comes from Greek and means something like “beyond” or “about,” and the word ethics, meaning “customs.”

This reflects what this branch of philosophy seeks to study. While ethics focuses on what people ought to do or which behaviors are morally right, metaethics examines what this ought means—in other words, the nature of moral judgments.

As a branch of philosophy, metaethics is incredibly broad and encompasses many arguments and frameworks. I couldn’t possibly list all of them here, so I’ll highlight just a few of the most popular ones.

Much of the information in this article comes from the excellent book by Andrew Fisher, Metaethics: An Introduction, which I highly recommend checking out.

On Categorizing Metaethics

Before diving into various metaethical frameworks, it’s helpful to get a rough overview of the kinds of questions that lead to different metaethical approaches.

There is no definitive way to organize these questions into a hierarchical structure that allows one to follow a simple decision tree to arrive at a preferred metaethical framework. Many have tried, but most graphs you find online are either incorrect or incomplete.

One of the challenges in categorizing metaethical frameworks is that they often don’t fit neatly into one category. Advocates of the same idea sometimes even disagree on where their framework should be placed in the broader landscape.

It’s better to think of metaethical frameworks as having various properties that can be associated with different questions. Another disclaimer: these properties are not strictly defined, and there is frequent disagreement about how they should be characterized. Keep this in mind as we proceed.

Properties of Metaethical Frameworks

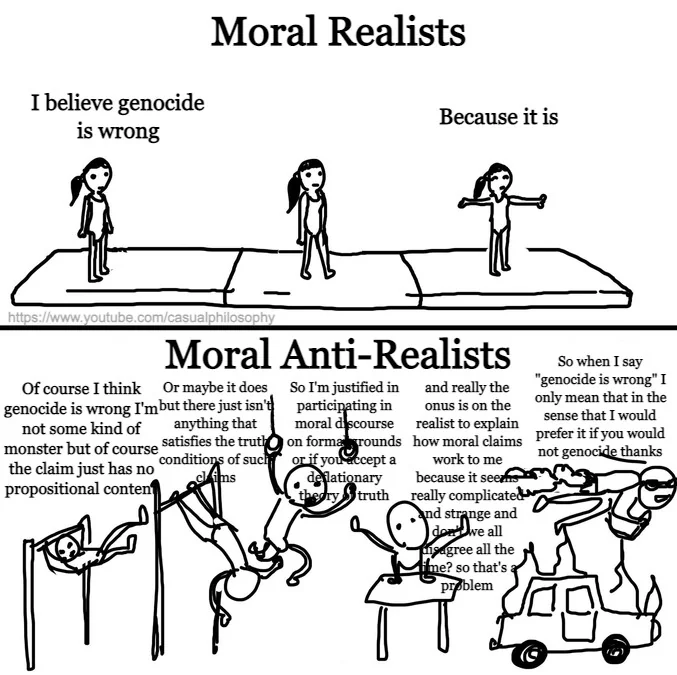

Moral Realism

One of the most fundamental questions one can ask about morality is: Does morality exist independently of people’s judgments? If someone answers “yes” to this question, they are considered a moral realist. Otherwise, they are classified as a moral anti-realist. We can think of these labels as representing the kinds of properties I mentioned earlier. A basic example of this concept is the following: If I steal something from someone and moral realism is correct, we can say that stealing inherently possesses the property of wrongness.

Cognitivism

We label someone a cognitivist if they claim, first, that moral judgments express beliefs, and second, that moral claims are either true or false. If either of these claims does not hold, they are called a non-cognitivist. For example, a cognitivist believes that the statement “torture is wrong” is either true or false.

Moral Naturalism

A moral naturalist argues that the properties of morality, or moral claims in general, can somehow be found in nature. In contrast, a non-naturalist believes that morality cannot be found in nature but exists in something non-natural, such as God.

These are some of the most basic properties a moral framework can have, but there are many more. A few others worth mentioning briefly include:

- Internalism vs. Externalism regarding motivation

- Descriptivism vs. Non-Descriptivism

- Atomic vs. Non-Atomic moral properties

- How is truth defined?

- Epistemological questions, e.g., Can we ever discover truths about morality?

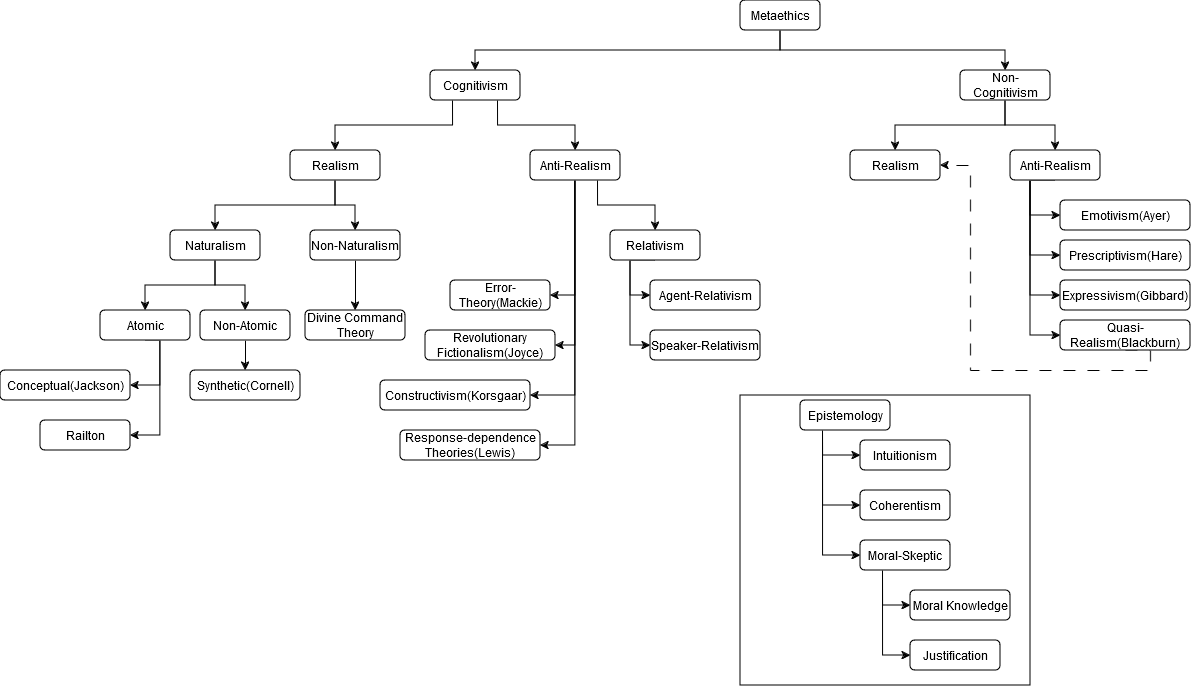

An Overview of Metaethics

Although I don’t think flowcharts provide the most accurate picture of the metaethical landscape, I’ve included one below because it helps to give a rough overview of what’s out there.

The chart might seem intimidating at first, but you already know some of the properties and the questions they are associated with. Once you’ve read the rest of this article, the chart should make a lot more sense.

Here’s how I plan to structure the rest of the article: In the following sections, I will explain the metaethical positions shown in the chart. Additionally, I will provide links to arguments that support and challenge these positions. Please note that I won’t list every possible argument here, but rather a selection of key ones. Also keep in mind that arguments against a realism position, strengthens non-realism approaches, but I wont list them there explicitly, this goes for other positions aswell.

By the end, you can reflect on which position makes the most sense to you and proudly declare your metaethical framework of choice!

Metaethical Positions

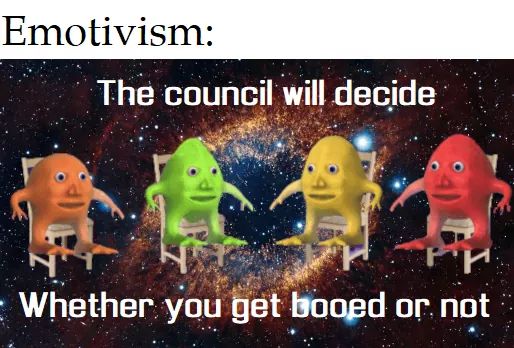

Emotivism

Overview

Emotivism (originating from A.J. Ayer) is the belief that when we make a moral judgment, we express a non-cognitive state. But what is a non-cognitive state? An example would be emotions. According to this view, when we say things like “stealing is wrong” or “killing is wrong,” we are not making a factual statement about the world. Instead, we are expressing an emotion. For example, saying “stealing is wrong” is equivalent to expressing “stealing, boo!” with a tone of disapproval or horror.

It’s important to emphasize that this does not mean we are describing an emotional state (e.g., “I feel angry about stealing”). Describing an emotion would make it a cognitive claim. Instead, in emotivism, we are expressing an emotional reaction.

Moral Truth and Disagreements

For Ayer, moral judgments do not have truth values. This means there is no such thing as a “true” or “false” moral judgment. Ayer puts it like this:

“If a sentence makes no statement at all, then there is no sense in asking whether what it says is true or false.”

But what about moral disagreements? People clearly argue about moral issues, such as animal suffering or gun control. How does emotivism account for this? According to Ayer, these disagreements are not about moral truths but about non-moral facts. For example, when debating gun ownership, the actual disagreement may center on whether gun ownership reduces or increases deaths, which is a factual question rather than a moral one.

Emotivism and Relativism

Emotivism is often confused with subjectivism, but they are distinct. Subjectivism holds that moral judgments like “murder is wrong” mean “I disapprove of murder.” In this view, moral claims describe the speaker’s mental state and are therefore cognitive.

Emotivism, by contrast, asserts that moral judgments do not describe anything. Instead, they express an emotional reaction. Consequently, questions about the truth or falsity of moral claims are irrelevant in emotivism.

For example, in relativism, one person might say, “Murder is wrong,” and another might say, “Murder is right,” and both could be correct within their respective frameworks. Under emotivism, however, these statements are not about truth or correctness at all—they are simply expressions of opposing emotions.

Arguments

Pro:

- Emotivism OQA Approach via Open Question Argument (OQA)

- Motivation Argument

- Morality Location Challenge

Contra:

- Emotions and Motivation of Others

- Severity of Moral Claims

- Convergence of Morality

- Moral Claims and Logic in Non-Cognitivism

- The Frege-Geach Problem

Error Theory

Error theory, developed by J.L. Mackie, makes two core claims:

- Moral judgments express beliefs and have truth values (cognitivism).

- There are no objective moral values (anti-realism).

From these premises, Mackie concludes:

“All moral judgments are systematically and uniformly false.”

Understanding the Position

An error theorist asserts that all moral statements are false. This includes statements like:

- “Torturing innocent children is morally wrong.”

- “Shooting random people in the street is morally wrong.”

- “Providing famine relief for starving children is morally good.”

Why does error theory hold that all these statements are false? The reasoning lies in its rejection of objective moral values. Mackie argues that there is no such thing as “objective moral value” in the world. Thus, asking “Is X morally right?” is akin to asking, “Does this water bottle have a brain and two hands?” In both cases, the answer is “no” because the objects in question lack the properties being attributed to them. Similarly, Mackie claims that no action or object has the property of “moral wrongness” or “moral goodness.”

Why Be Moral, Then?

If all moral claims are false, does that mean we should abandon morality? Not necessarily. Mackie suggests that moral practice is still pragmatically justified. Morality serves important purposes, such as:

- Maintaining social harmony.

- Facilitating interpersonal relationships.

In this view, the usefulness of morality—not its truthfulness—justifies its continued practice. While moral judgments may be false in a literal sense, their functional role in society makes them valuable.

Arguments

Pro:

- Challenge to the Queerness Argument 1 as response to The Queerness Argument

Contra:

For more see my newest paper summary on it.

Moral Realism and Naturalism

Overview

To be a moral realist is to believe that moral properties are real and exist in some sense independent of what people think.

At first, the idea that moral properties exist may seem strange—after all, they don’t exist in the same way that chairs, oranges, or clothes do. However, we often accept the existence of abstract or less tangible concepts, such as:

- Love

- Society

- Numbers

- Atoms

- Time

If we agree that these concepts exist, despite their abstract nature, why shouldn’t moral properties also exist?

Naturalism

Within moral realism, naturalism holds that moral properties are part of the natural world and can be understood through empirical or conceptual analysis. There are two main approaches to argue for naturalism:

- Frank Jackson’s conceptual analysis.

- Cornell realism’s posteriori analysis.

Conceptual Analysis (Frank Jackson)

Frank Jackson argues that moral properties are natural facts that can be identified through conceptual reasoning, independent of experience. He employs the Ramsey–Lewis method, a technique used to define theoretical entities by “telling a story” about them.

Example: Explaining an Electron

How might we define an electron, proton, or neutron without relying on the technical language of physics? By describing their roles and interactions:

“There is one kind of thing, and another, and yet another.

Instances of the first kind orbit a clump of instances of the second and third kinds.

The first and second kinds attract each other, but instances of the same kind repel each other.

The third kind exhibits no attraction or repulsion to others of its kind, yet some force keeps the second kind together in a clump despite their mutual repulsion.”

This “story” provides a definition without directly naming concepts like electrons or protons. When we observe phenomena in the real world that fit this description, we identify them as electrons, protons, and neutrons.

Applying the Method to Morality

Jackson proposes using a similar method to define morality:

Collect Consensus Statements

Identify moral discussions where consensus has been reached.List Associated Truths

Write down all the truths associated with moral terms in these debates.Abstract Moral Properties

Replace moral terms (e.g., “wrong,” “right”) with variables like \(a_w\) (for wrongness), \(a_r\) (for rightness), or \(a_g\) (for goodness).

For example, such a list might look like this:

- Something cannot possess both \(a_w\) (wrongness) and \(a_r\) (rightness) simultaneously.

- If someone claims \(X\) has \(a_w\) and another claims it doesn’t, one of them must be mistaken.

- If we judge \(X\) to have \(a_w\), we are motivated to avoid \(X\).

By analyzing this list, Jackson argues that we can identify moral properties as whatever satisfies these conditions in the real world.

For this method to succeed, the “story” about morality must be precise enough to uniquely identify one thing—moral properties—in the natural world. If it fails to do so, the definition risks ambiguity or irrelevance.

Synthetic Moral Realism (Cornell, Railton)

Synthetic moralists argue that the existence of morality and moral properties provides the best explanation for certain phenomena. By postulating that moral properties are real and exist in the natural world, they claim to improve our understanding, much like the atomic model in science—while it may not represent ultimate truth, it remains our best explanatory framework.

Cornell realists hold that if natural moral properties offer the best explanatory account of morality, then moral properties are real, and moral realism is correct.

Their primary argument can be summarized as follows:

- Why do we believe that a wrongful murder is morally wrong?

- The best explanation, according to Cornell realists, is that moral properties like “wrongness” actually exist and are part of the natural world.

This explanatory role of moral properties supports their claim that moral realism is not just plausible but the most reasonable model we currently have.

Atomicness and Explanatory Power

Cornell realists and Railton differ on two key aspects:

Explanatory Role of Moral Properties

- Cornell realists: Moral properties having explanatory power is sufficient to affirm their reality.

- Railton: Explanatory power is merely necessary but not enough by itself (see necessary and sufficient conditions).

Atomic vs. Non-Atomic Morality

- Railton: Morality is non-atomic and reducible—moral properties like “goodness” can be defined through hypotheses, trial, and error.

- Cornell realists: Morality is atomic and irreducible—it cannot be broken down into simpler components.

Jackson offers a contrasting viewpoint by arguing that moral properties can only be defined a priori (independent of evidence), emphasizing conceptual rather than empirical analysis.

Arguments

Pro:

- Severity of Moral Claims

- Convergence of Morality

- Truth of Morality

- Supervenience Argument for Naturalism

Contra:

- Observed ‘Relativism’ Argument

- The Queerness Argument

- Epistemological Queerness

- Conceptual Analysis Counter but can be countered.

- Conceptual Analysis and OQA

- Counter-Supervenience Arguments

- Motivation and Natural Properties

Non-Naturalism

A moral non-naturalist would argue that “killing is wrong” is true because killing possesses the non-natural property of wrongness.

What is meant by a non-natural property? A non-natural property is one that cannot be directly observed in nature; instead, it exists in “another plane of existence.” Examples of non-natural properties include:

- Plato’s Theory of Forms

- Religious concepts, such as the idea of God in Christianity

- The astral plane

- Folklore about ghosts

Why would anyone hold such a position? The motivations and arguments for moral realism still apply, but in addition, there are arguments supporting non-naturalism.

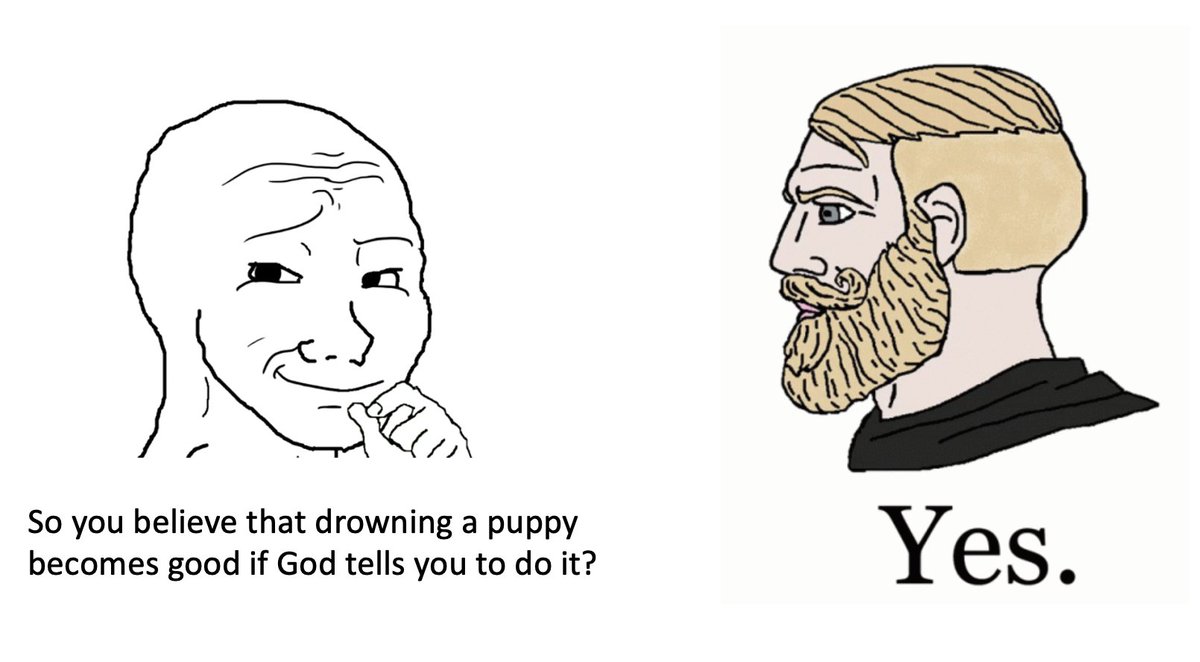

Divine Command Theory

The underlying assumption of this theory is that God exists. This does not mean that simply believing in God necessitates accepting this theory. For example, the Christian philosopher Thomas Aquinas favored natural law theory instead.

The basic premise of Divine Command Theory is that what is moral is what is commanded by God.

There are several distinctions that can be made within this theory:

- Should one follow God’s will, or His commands?

- Do God’s commands make something right, or are God’s commands identical with what is right?

Arguments

Pro:

- Severity of Moral Claims

- Counter to the Arbitrariness of Morality Argument see contra.

- Russ Shafer-Landau’s Argument

Contra:

Quasi-Realism

After G.E. Moore popularized the Open Question Argument (OQA), cognitivism lost favor, and non-cognitivism became more popular. However, later an argument emerged that left non-cognitivism in a difficult position: the Frege-Geach Problem.

The main proponent of quasi-realism is Simon Blackburn. Importantly, quasi-realism is not another moral framework, but rather an explanation for why our moral practices appear to be realist, even though realism is actually false.

Do not be confused: this is still a non-cognitivist position. Blackburn argues only that we should give more respect to the realist position.

Arguments

Pro:

- Severity of Moral Claims

- Blackburn’s Counter to the Frege-Geach Problem via The Frege-Geach Problem

- Why Realism When Non-Cognitivism Is True?

- Why Non-Cognitivism Instead of Realism

Contra:

- Quasi-Realism Dilemma: either quasi-realism cannot be identifies with non-cognitivism, or it can be identified with non-cognitivism, but it cannot capture all features of morality.

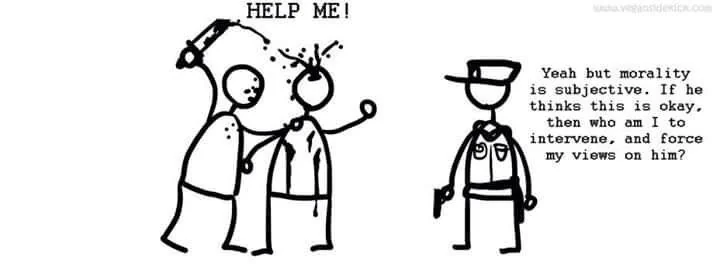

Agent-Relativism

The basic premise of agent-relativism is that something is right or wrong depending on the moral framework of the agent. For example, someone protesting against stealing is right if and only if it is prescribed by their moral framework. This does not mean that what is right is simply whatever we want it to be, as it could still be forbidden by our moral framework.

Agent-relativism makes two important claims:

- There is no shared universal moral framework between agents.

- It makes no sense to say that one moral framework is “more correct” than another.

Why agent-relativism? We can look at different actions by non-humans to understand the motivation behind it:

- Do we think a tiger is morally wrong for eating humans?

- Do we think a hurricane is morally wrong for killing humans?

Most people would probably not say that the tiger or the hurricane has any kind of moral responsibility. What about people with severe mental illness? Can they do something wrong, i.e., be morally responsible?

What agent-relativism allows us to say is that moral responsibility depends on the mental capacities of the agent.

It is important to note that such a position would lead to the conclusion that, if Hitler was exterminating the Jews while following his own moral framework, we could not say he was morally wrong.

Another motivation for agent-relativism is that, given there are many moral frameworks and no standard to judge which one is right or wrong, we should simply accept relativism.

Arguments

Pro:

Contra:

Speaker-Relativism

Some non-moral claims are relative. For example, “Is a car fast?” is relative. Is a car fast compared to someone walking? Yes. Is a car fast compared to a rocket? No.

Can we apply the same idea to moral claims?

If we say “killing is wrong,” is this true for all species, all societies, and all times, or is it relative to different moral frameworks? A speaker-relativist would argue that it is relative.

How does speaker-relativism differ from agent-relativism? Let’s imagine a scenario where a man is throwing puppies off a bridge. In an agent-relativist framework, what matters is the moral framework of the person doing the throwing. In comparison, in speaker-relativism, we would also be interested in the moral framework of the person saying that throwing puppies off the bridge is wrong.

Arguments

Pro:

Contra:

Fictionalism

There are two main branches of fictionalism: hermeneutic fictionalism and revolutionary fictionalism. Hermeneutic fictionalism is a descriptive theory that explains what moral practice is like, while revolutionary fictionalism is a prescriptive theory that explains what morals should be like.

Hermeneutic Fictionalism

Our moral practice is based on make-believe. For example, when we say “giving money to charity is right,” we do not literally believe that giving money to charity is right, but rather we engage in a kind of make-believe about it.

We can compare this to playing a game. When playing a game, one might ask, “What is the best path forward?” Certain things in the game are also true or false. These fictional claims are true within the context of the game, but not literally true.

Thus, hermeneutic fictionalism allows for claims like:

- a) Moral claims can be true according to the moral fiction, which allows us to reject error theory.

- b) Moral claims can be true even if there are no moral properties or facts, allowing us to avoid ontological debates about what moral properties are.

The major challenge to hermeneutic fictionalism arises when we say things like “racism is wrong.” It does not feel like fiction. Even more so, when making decisions about life and death, it does not feel like fiction.

A hermeneutic fictionalist would rebut by saying that we are so familiar with moral language that we do not realize we use it like fiction, much the same way we sometimes use metaphors without realizing it.

But if this is true, how can we differentiate between reality and make-believe? Why isn’t math, science, love, or time also fiction by the same argument? Especially because studies have shown that most people can differentiate between fiction and non-fiction.

Revolutionary Fictionalism

Revolutionary fictionalism believes that our moral judgments are systematically and uniformly false and that making false claims is not as beneficial as starting to engage in moral fiction. Imagine a history teacher teaching about hobbits as though they were historical fact—this would be wrong. Revolutionary fictionalism argues that we do something similar when making moral claims.

Thus, we believe what we say, but it is wrong, which leads fictionalists to two options:

- a) Eliminativism: abandon moral talk altogether.

- b) Revolutionary fictionalism: agree that moral talk is systematically false, stop believing what we say, and start pretending.

For revolutionary fictionalism, the challenge is to show that (b) is better than (a)—that it is more beneficial to engage with fiction and give up reality.

Arguments

Pro:

Contra:

Non-Descriptive Expressivism

So far, we have assumed that if a moral judgment expresses a belief, then this judgment can be thought of as a description of some kind.

Horgan and Timmons argue that this is a mistake. Instead, we should think of moral judgments as non-descriptive.

For example, the claim “murder is wrong” expresses a belief, but it does not have the property of wrongness.

This view supports cognitivism and rejects realism, while not adhering to error theory. Beliefs do not describe the world as having any moral properties or facts. Instead, they are separated into two categories:

- Is-commitments: non-moral beliefs.

- Ought-commitments: moral beliefs.

Constructivism/Response-dependence Theory

Moral Skepticism

Moral skepticism is an epistemological claim, meaning it pertains to the process of acquiring moral truths.

One can be skeptical about various aspects of moral knowledge. For example, one could deny the possibility of acquiring moral knowledge, or one could deny that there is justification for morality.

It asserts that we cannot know:

- Whether testing suffocating gas on political prisoners is morally right or wrong.

- Whether the Holocaust is morally right or wrong.

- Whether producing artificial famine is morally right or wrong.

Arguments

Pro:

Contra:

Intuitionism

Intuitionism holds that epistemological moral progress stops with moral beliefs that are justified through non-inferential means.

So, how do we justify these claims? An intuitionist answer is prior reflection: Some moral beliefs are self-evident, and from there, we can make inferences.

Arguments

Pro:

Coherentism

The premise is that moral knowledge is possible. The basic idea is that moral beliefs are justified if they form a coherent set of beliefs.

This idea might seem a bit circular, similar to how a Christian might argue that God is justified because of the Bible, and the Bible is justified because of God. However, there is an important difference: the Bible and God example relies on a linear form of justification. Coherentism, on the other hand, relies on a holistic account of justification. That is, a raft stays afloat not because of any one particular plank, but because of the combined structure of all the planks together.

Thus, the belief that giving money to charity is right is correct if it is part of a coherent set of beliefs.

The last thing we need to explain is: what does “coherent” mean? We say something is coherent if it fulfills the following criteria:

- Logical consistency: The set cannot contain a belief and its negation.

- Evidential consistency: The weight of beliefs needs to be balanced.

- Connectedness: The set of beliefs cannot be completely unrelated (e.g., “humans have two arms” and “monkeys are beautiful”).

- If we have two sets of beliefs, the one that has more beliefs and is coherent is considered more coherent.

The biggest criticism of coherentism is that the coherent argument does not take truthfulness into account. This means that we may have a coherent set of beliefs that is actually false.

Arguments

Pro:

Arguments

Open Question Argument (OQA)

Introduction

The Open Question Argument (OQA) (although controversial, as not everyone agrees it’s valid) by G.E. Moore suggests that “good” can’t be defined through any natural property in the world but can only be understood as “good” in itself. This creates a gap: if the descriptive facts of the world don’t tell us what “good” is, then what does?

The Argument

Questions like “Does a triangle have three sides?” or “Did a virgin have sex?” or “Does a chessboard have four corners?” seem strange because the answer to these questions is already contained within the question itself. We know a triangle has three sides because it is a triangle. We know a chessboard has four corners because it’s a square. Moore calls such questions, where the answer is obvious from the question, closed.

He compares them to open questions, where the answer is not clear from the question itself, such as “Who is the prettiest person alive?” or “Should everyone have a gun for self-protection?” These questions are open because terms like “prettiest” and “should” make the answers unclear.

We can use this distinction to interrogate definitions of things. If I ask the question “Is X the same as Y?” and the question is open, we know that X is not defined as Y.

We can now apply this to the concept of “good” in an attempt to define it. We might ask:

- “Is good pleasure?”

- A sadist might get pleasure from inflicting harm upon someone. Does this make it good?

- Understanding “good” and “pleasure” does not settle the matter.

- “Is good what makes us happy?”

- I might have planned a lazy evening relaxing on the couch, but when my parents call me to help them, I may be unhappy. Does this mean it’s not good because of that?

- How is “happy” defined?

- “Is good what makes the gods smile?”

- Would this mean it’s good to sacrifice our child if the gods want it?

- What do terms like “sacrifice” and “wants to” mean in this case?

Moore believes we can raise these types of objections to every possible definition of “good,” making it an open question. Thus, “good” is indefinable and can only be understood through itself.

The Implications

If “good” can’t be defined through anything besides itself, it can’t be defined through any properties, whether natural or non-natural.

In a way, this is similar to Hume’s Law, which asserts that we can’t derive ethical statements from descriptive statements—meaning, you can’t get an “ought” from an “is.”

This led to non-cognitivism becoming popular after G.E. Moore for two reasons. Non-cognitivism suggests that “good” is an expression of attitude, which aligns with Moore’s implication that moral values can’t be derived from natural facts.

One OQA Counter

The first counter to the OQA is the following: if a person believes that “that which is good is what we desire,” then the OQA is not an argument against it, but rather an assertion that the given definition is wrong.

Moore would argue against this by saying that when defining moral statements, popular opinion is much more important than in fields like mathematics, where we can simply say that the person is confused. Thus, if people think that the question “What is good?” is open, this could be a good reason to think that it is truly open.

Motivation Argument

One counter to cognitivism and in favor of non-cognitivism, such as emotivism, is the motivational aspect of moral judgment.

If morality is a fact—whether natural or non-natural—why are we motivated to follow it?

For example, if you genuinely believe that vegetarianism is morally correct but then ask, “What does this have to do with me?” one might think that the person didn’t really understand what morally correct means.

Thus, it seems that moral judgments have something built into them that motivates us to act on the fact and do something with it.

Emotivists do not have this problem. If moral judgments are emotions, it makes much more sense why one would act on them. For instance, one might think hitting a dog is wrong, but if it were just a fact, it wouldn’t motivate us. However, if morality were an emotion, it would motivate one to stop someone from hitting the dog.

Morality Location Challenge

Imagine you see a man on top of a bridge, throwing puppies from the bridge into the water to kill them. If we now take an empiricist approach, where can we sense the moral wrongness of this? We can see the puppies, we can perhaps hear them cry, and maybe feel their tears. We might even build a device to read their brain activity, and we could detect that the man is gleeful and fully aware of his actions. But again, where is the moral wrongness?

To see the moral wrongness, we need to look within ourselves. There it is. This speaks to non-cognitivist theories and challenges moral realism.

Instinctual Emotions Argument

Imagine you are outside wandering the streets and see an innocent, weak homeless man getting beaten. You would say, “This is wrong.” As we established previously (see Morality Location Argument), this wrongness is not in the situation but within yourself. If you observe your thought pattern during this exchange, you will notice that you do not think about the situation analytically (e.g., “If P then Q, and P is true, so Q”). Instead, the wrongness you feel is more instinctual, i.e., emotional.

Emotivism OQA Approach

If the OQA is true, then moral judgments are not describing something natural; thus, they must describe something non-natural. But this means they are not empirically verifiable; they would be something metaphysical, and metaphysics is often regarded as speaking nonsense (see Ayer’s paper “Claims of Philosophy”). Therefore, moral judgments cannot be described by non-naturalism either.

Thus, we should reject cognitivism and accept non-cognitivism, specifically emotivism. Emotivism does not need to explain what moral properties are, because they do not exist (this is the non-cognitivist view).

Emotions and Motivation of Others

If moral judgments are really just emotions, so that when I utter “Torturing is morally wrong,” I am simply expressing my feelings, why should anyone besides me be motivated to act against the injustice? Or why should anyone pay attention to me when I am expressing my feelings, especially if they do not care about them?

If one utters a moral statement, do we not think that this is universally motivating—not only for me but also for others—even if they do not particularly care for me?

Observed ‘Relativism’ Argument

If there are objective moral theories, why do different societies not have the same moral judgments? For example, the Aztecs thought sacrificing humans was acceptable, and indigenous tribes in the Amazon left behind those who were too old to keep up. Even if both parties are fully informed—e.g., two people who are fully informed on the abortion debate—they might still have different views on it.

The Queerness Argument

What is morality? It should be independent from our beliefs. Just because many people think something is wrong or right doesn’t make it right or wrong; it should be accessible to us, meaning there needs to be a way through which we can determine whether actions are right or wrong. Lastly, it needs to give us a reason to act, irrespective of our desires—i.e., just because I want to steal doesn’t mean I should.

The argument against realism now is that, if “objective moral values exist, they would be utterly different from anything in the universe.” Why? We might say that a coffee machine fulfills all our prior defined properties: it exists independently from our mind, is accessible to us, and gives us a reason to act. However, this reason to act is not independent of us—it depends on our psychological state, namely, our desire for coffee. But if moral values existed, they would give us a reason to act irrespective of our psychology. For example, we would know “stealing is wrong” regardless of our current desires.

Epistemological Queerness

If we accept that morality is “utterly different from anything else in this world,” wouldn’t it naturally follow that we would need an “utterly different way to access it”?

Meaning, morality would become inaccessible by normal means.

Insensitivity of Psychology

A friend promises to meet you at the pub, but he becomes depressed. Should he still go to the pub? Error theorists would say that if keeping a promise is good, then he should go, because “good” is irrespective of psychology. But many people might not agree and would argue that if he’s depressed, he doesn’t have to keep his promise. This suggests that morality is not insensitive to people’s psychology.

Challenge to the Queerness Argument 1

Error theories and other theories that assume naturalism—how would they argue against a Platonist who believes that the form of “god” exists? The Queerness argument that “morality is utterly different from anything else” is only as strong as the defense of naturalism.

Moorean Shift

This argument is called the Moorean Shift. G.E. Moore first deployed it against skepticism:

- I know I have two hands and the sun is in the sky.

- If the skeptic is correct, then I cannot know that I have two hands and that the sun is in the sky. Therefore: 3. There is a problem with the skeptic’s argument.

You can apply the same logic to moral claims:

- “Torturing children is wrong” is true.

- If error theory is correct, then “Torturing children is wrong” is false. Therefore: 3. Error theory is wrong.

For this argument to work, one needs to know at least that some moral claims are true.

Severity of Moral Claims

When deciding where to eat, if you and your friend disagree, you might flip a coin to decide.

However, this would not be sufficient for moral decisions, such as “Is the death penalty moral or not?”

It seems to us that moral judgments are more than simple preferences.

One possible explanation for this is that moral statements point to something true that exists in the world, as moral natural realists claim.

Convergence of Morality

If we were to put individuals from around the world in a room and ask them to draft the ten most important moral rules, would we expect the rules they create to be relatively similar? Or not?

If we think they would be similar, doesn’t this suggest some objectivity, and with it, some form of moral realism?

Truth of Morality

If one person thinks late-stage abortion is wrong and another thinks it’s okay, and realism is false, meaning we can both be correct, then it’s hard to explain why we cannot accept that both are right.

Another thing that points in the same direction is the concept of moral progress:

- Women are allowed to vote.

- We abolished slavery.

- Children no longer need to work.

If we do have moral progress, then this would suggest we are moving toward something, and this “something” would be objective. Thus, this points toward realism.

Conceptual Analysis Counter

Jackson used the Lewis-Ramsey method to define what goodness is, but crucially, he only defined what it is; he didn’t claim that it existed.

If I compare this to math, the Ramsey-Lewis method just gives a definition in the appropriate language, but it does not provide proof that something with this definition exists.

One could use the same method to define unicorns, by telling a story about them.

Counter to the Counter

Jackson would argue that the difference between a unicorn and morality, as described using this method, is that there is no proof for a unicorn. But there is proof for morality, since we use it regularly.

Conceptual Analysis and OQA

OQA can possibly be used against Jackson. After we have defined morality using a story, we can ask whether the question of whether morality is defined over the story is open or closed.

Jackson would argue that whoever thinks that morality, as defined in his story, is an open question and not a closed one, isn’t part of the mature folk who have discussed morality. In other words, they either didn’t understand it or are too ignorant.

Supervenience Argument for Naturalism

We say that \(X\) supervenes on \(Y\) if, in any two situations (\(X\), \(Y\)), \(Y\) can only be different if \(X\) is also different.

An example of this would be the following: only when the molecules of a table are different can the table itself be different.

From this, we can establish the so-called counterfactual test. For instance, if your friend starts drinking and you think it’s because his wife beats him, a good test to see if you’re right would be to ask yourself: would your friend stop drinking if his wife stopped beating him?

We can then apply this test to understand why we think a wrongful murder is wrong. Would we still judge the murderer’s action as wrong if, as a matter of fact, the action was not wrong? The intuitive answer to the question is “no.” If the action were not wrong, we wouldn’t think it was wrong.

This means that, if the counterfactual test is valid, then synthetic realism is correct, because the wrongness depends on the action, and asserting that the property of wrongness exists has a genuine explanatory role.

Counter-Supervenience Arguments

If non-realists are right, there are no moral properties. Thus, asking how our belief would change if we removed the morality property doesn’t make sense.

Counter to the Counter

If the synthetic-realist moral theory is true, then needless suffering has the property of moral wrongness.

Because of supervenience, if an action did not have the property of being wrong, then it would not bring needless suffering. Why? Because the action supervenes on morality.

In other words, if an action is right or wrong, then the moral property associated with it also needs to change.

We can rewrite the counterfactual test as follows: imagine a case where a murder didn’t involve needless suffering, and after being murdered, the victim jumped up and asked for more. Would this action then be wrong? Intuitively, we would say “no.”

This means that, if the counterfactual test is valid, and if the moral theory is correct (i.e., needless suffering is morally wrong), then it seems that moral properties do have an explanatory role.

Motivation and Natural Properties

When we use words like “ought” or “should,” we label them as normative, in contrast to descriptive. These words are used to persuade people to act in a certain way. Normativity allows us to talk about actions being blameworthy or praiseworthy.

If realism is correct and moral properties exist, they would need to guide us toward action. It would be implausible to say that moral properties exist but do not move us in any way. Therefore, if normative properties exist, they must be intrinsically motivating.

For example, if I lie to a friend and this action has the property of wrongness, then this wrongness should motivate me to refrain from lying. This is different from natural properties. If my bike is dirty, I might choose to clean it—or I might not. Moral properties, however, should motivate action regardless of one’s psychological state.

Counter

Moral properties do not necessarily have to be intrinsically motivating. Instead, the motivation could come from within us. For example, through evolutionary psychology, humans have evolved to respond to certain moral properties because such responses promote survival.

Epistemological Divine Command Argument

If something is right or wrong if and only if God commands or forbids it, then it cannot be discovered through natural means because God is outside the universe and independent of the natural world.

Arbitrariness of Morality Argument

This argument is often used against utilitarianism but can also be applied to divine command theory.

Because God is sovereign, He could theoretically command actions like child sacrifice, and in that case, child sacrifice would be considered moral. But if we say that anything can be deemed immoral, wouldn’t child sacrifice fall under this category?

Thus, we are left with two options:

- We must either abandon divine command theory, or

- We must accept that certain things (like child sacrifice) are always immoral, regardless of God’s commands.

Counter to the Arbitrariness of Morality Argument

In the arbitrariness argument, we posited that God could theoretically command us to do anything, and it would be moral, even if we felt it was immoral. For example:

a) Some actions, such as genocide, are always morally wrong.

b) God could command any action, including genocide.

c) If divine command theory is true, then genocide could be morally right.

We are left with two options:

- One could reject (a) and argue that moral intuitions are arbitrary.

- Or one could reject (b) and claim that God only commands actions that are good because God’s character is infinitely good.

Russ Shafer-Landau Argument

Russ Shafer-Landau argues that moral properties exist and are non-natural.

He defines a non-natural property as one that would be eliminated once we have perfected science, meaning that only natural properties would remain in a perfected science.

For example:

- If perfected physics requires quarks to exist, then quarks are natural properties.

- If perfected chemistry requires sodium to exist, then sodium is a natural property.

Shafer-Landau argues that morality is a property that would be eliminated, and thus it is non-natural. He believes this because ethics is not a natural or social science.

The distinction between natural sciences and ethics is that natural sciences discover their principles or axioms posterior—meaning through evidence and experimentation. In contrast, ethics discovers moral truths a priori, meaning without relying on empirical experimentation but through reasoning.

Why Shafer-Landau believes ethical truths are discovered a priori:

Multiple Realizability: Any mental state can be realized in an indefinite number of ways. For instance, if an alien winced, we would say they are in pain, regardless of how their biology functions.

- Shafer-Landau argues that this applies to moral properties as well. An action can be wrong even though it may have many different properties (e.g., it might cause pain or pleasure, it might be legal or illegal, etc.).

- Because there is no set of properties with which we can define morality, this leads him to think that morality is irreducible.

Property Dualism: Philosophers who argue that mental states cannot be reduced to physical ones either follow Descartes, claiming the mind is a separate substance from the body (Substance Dualism), or follow Jackson, claiming that mental properties are distinct from physical ones (Property Dualism).

- Shafer-Landau’s non-naturalist moral realism follows the Jackson route. He believes that non-natural moral properties are properties of natural substances, as opposed to divine command theory, which argues that non-natural properties are properties of non-natural substances.

- This means that Shafer-Landau’s approach does not require the existence of non-natural substances, which would raise questions about their ontology (i.e., what they are).

In contrast to the natural sciences, philosophy does not rely on empirical results to make claims. A metaphysician does not need grant money to purchase lab equipment, for example. This supports the idea that philosophical claims are not dependent on empirical discoveries, further reinforcing Shafer-Landau’s belief that moral properties are non-natural rather than natural.

Moral Claims and Logic in Non-Cognitivism

If moral statements really express a non-cognitive state, such as emotions in emotivism, then statements like “stealing is wrong” would be translated to “stealing, boo!” or “boo!” expressing disapproval.

However, this raises a question: how can we make sense of such statements in logical contexts?

For example, consider the statement “Killing is wrong or lying is wrong.” Under emotivism, this would translate to “Killing, boo! or lying, boo!” This seems just as nonsensical as saying “WOW or Ugh!"—a combination of emotional exclamations that do not form a coherent logical proposition.

It’s like trying to make logical arguments but replacing the statements with gibberish. In a logical framework, the use of emotive expressions in place of actual propositions doesn’t seem to preserve meaningful reasoning or coherence.

The Frege-Geach Problem

If non-cognitivism is true, then the meaning of moral claims should vary depending on whether they are asserted or not. However, in practice, we don’t usually think this way.

We can make moral claims by uttering a statement such as “Killing is wrong,” but we can also make moral claims using other features of language, such as conditionals and disjunctions.

For example, consider a conditional: “If child sacrifice is wrong, then Abraham was wrong in attempting to sacrifice Isaac.” Importantly, in this case, we are not asserting that child sacrifice is wrong; we’re just considering the consequences of the claim.

Another example is a disjunction: “Child sacrifice is wrong or lying is wrong.” Here again, we are not asserting that either of these actions is wrong, merely stating a possibility.

Non-cognitivists claim that when we make a moral claim, we are expressing a non-cognitive state. However, when we do not make a moral claim (as in a conditional or disjunction), we are not expressing a non-cognitive state.

This means that when we say “Child sacrifice is wrong,” we are expressing a non-cognitive state. But when we say “If child sacrifice is wrong, then Abraham was wrong in attempting to sacrifice Isaac,” we are not expressing a non-cognitive state, even though we still refer to a moral claim.

Thus, the meaning of moral claims seems to change depending on the context. In one case, when we make a direct moral statement, we express a non-cognitive state. In another, when we use a conditional or disjunction, we don’t. This creates a problem because the meaning of moral claims should ideally be consistent, regardless of how we express them.

To make this clearer:

- “Killing is wrong” is a moral statement, so it expresses a non-cognitive state.

- “If killing is wrong, then soldiers should not kill” is not a moral assertion; here, “killing is wrong” takes on a different meaning.

The problem arises because it seems illogical that the meaning of moral claims should change depending on the literary device we use to express them. This inconsistency leads to issues when applying logical reasoning.

Let’s consider modus ponens, a common form of argument:

- A

- If A, then B Therefore,

- B

For non-cognitivists, in (1) A is asserted, but in (2) A is not asserted. In other words, A changes between (1) and (2), making it unclear whether (3) logically follows.

For example:

- Torture is wrong

- If torture is wrong, then I am wrong when I torture children. Therefore,

- Torturing children is wrong.

This seems to make sense. But when we apply the non-cognitivist framework, it gets translated as:

- Torture is boo!

- If torture is wrong, then I am wrong when I torture children. Therefore,

- Torturing children is wrong.

Most notably, only (1) is translated into an emotive expression (“boo!”), while (2) remains unchanged as a conditional. This is because only (1) is an assertion, while (2) is a conditional.

This causes a breakdown in the argument because for modus ponens to work, the statement \( A \) in (1) and (2) must be the same. But under non-cognitivism, they are not, leading to a failure in the logical structure.

Thus, under a non-cognitivist view, one of the most important rules of logic no longer works for moral claims. This problem does not arise for cognitivist positions, where moral claims retain their logical consistency across different forms of expression.

Blackburn Counter to the Frege-Geach Problem

Blackburn offers a solution to the Frege-Geach problem by introducing the notion of sensibility. He defines sensibility as a set of properties that shape how one reacts to a given situation.

For instance, some people may become angrier at injustice than others, while others may have a disposition to cry at acts of cruelty.

People, in general, do not prefer certain sensibilities over others, but they tend to favor sensibilities that lead to consistent behavior rather than erratic or unpredictable responses.

With this in mind, Blackburn is now in a position to preserve modus ponens without relying on discussions of validity or truth.

Let’s revisit the example:

- Torture is wrong.

- If torture is wrong, then I am wrong when I torture children. Therefore,

- Torturing children is wrong.

In this context, we can interpret (1) as expressing an attitude of disapproval toward torture. Meanwhile, (2) conveys an attitude toward moral sensibility, meaning it expresses disapproval toward people whose moral sensibility includes both a disapproval of torture and a lack of approval of the speaker torturing children.

The key point here is that moral sensibility must be consistent. If we were to deny (3), our sensibilities would be inconsistent because we would be condoning an act (torturing children) that contradicts the disapproval expressed in (1) and (2).

Thus, the validity of modus ponens is preserved in Blackburn’s framework by maintaining a consistent moral sensibility. Rather than focusing on the truth or validity of statements in the traditional logical sense, the consistency of one’s moral reactions is what ensures the coherence of the argument.

Why Realism When Non-Cognitivism Is True?

Imagine a world with no moral truths, where moral language only expresses emotions like “booh!” (disapproval) or “hurray!” (approval). In such a world, we could not engage in more sophisticated moral discussions about what is right or wrong, because moral claims would just express feelings rather than facts.

To have meaningful moral debates, we’d need a framework where moral statements can be true or false—something akin to moral realism. Without moral truths, our moral discourse would be limited to simple emotional expressions, making complex moral reasoning difficult. Thus, even in a non-cognitivist world, moral language might evolve toward realism to support deeper moral discussions.

Why Non-Cognitivism Instead of Realism

Blackburn presents three arguments against moral realism in favor of non-cognitivism:

Economical:

Non-cognitivism is more economical, requiring only the natural world and people’s states. Realism, on the other hand, is more complex and requires the existence of moral facts, making it less economical. This argument rests on the idea that simpler theories are often more accurate.Moral Psychology:

Blackburn argues that moral judgments must motivate action, and this motivation stems from desires, not beliefs. According to Humean internalism, beliefs and desires are distinct, so moral judgments cannot be beliefs. This undermines cognitivism, which treats moral judgments as beliefs that do not inherently motivate action.Supervenience:

Supervenience suggests that identical natural properties imply identical moral properties. Blackburn argues that it’s implausible to “read off” moral properties simply by understanding natural ones. For instance, we can’t just observe pain to conclude it’s wrong without a moral framework. If moral theories merely rest on natural facts, they become redundant and fail to guide decision-making.

Together, these arguments suggest that non-cognitivism is a more viable theory than realism.

Normative Reason and Agent Relativism

Imagine a hot spring in front of you. Wanting to jump in and bathe represents a motivating reason. However, if the water is scalding hot and you would die, the reason not to jump in is a normative reason. Normative reasons are those that suggest what one should do, independent of their current motivation.

If an agent has a reason to act in a certain way, but is not motivated to do so, this challenges agent relativism. For example, a shy person who accidentally ends up at a party may have a reason to participate (a normative reason), even though they lack the motivation to do so. This scenario illustrates external reasons — reasons not tied to an agent’s internal desires or motivations.

If external reasons exist, this suggests that moral judgments, like condemning Hitler, can be independent of one’s moral framework, challenging agent relativism.

Speaker Relativism and Universality of Moral Claims

When people make moral claims, they typically present them as universal (“Murder is wrong”), rather than caveating them with “only for me.” This implies that, according to speaker relativism, when people assert moral claims, they may not be speaking the truth in an absolute sense, since the truth would be relative.

This leads to error theory — the view that all moral claims are false because their truth is relative. A counter-argument for speaker relativists could be that moral truth is relative even if our language does not explicitly convey this relativity.

Disagreements in Relativism

In moral disagreements, a moral realist would say one party is objectively wrong. A relativist, however, would claim that each person is simply operating within their own moral framework, meaning they are not mistaken but are instead having a faultless disagreement. If people share the same framework, they might agree on moral issues.

A critique of this view is that if “abortion is wrong” only means “abortion is wrong for me,” then disagreements about moral claims become meaningless, as they no longer express shared values but rather individual perspectives.

Epistemological Regression Argument

To know something, we need to be justified in believing it. For example, to know that a cat is in the garden, we need to see or hear it. However, this leads to an infinite regress:

- I know the cat is in the garden because I see it.

- But why do I believe I see it?

- Because my eyes are open.

- Why do I believe my eyes are open?

- And so on…

There are several ways to address this problem, which correspond to different epistemological positions:

- a) Infinite regress in beliefs: Accept that belief justification requires an infinite regress.

- b) Skepticism: The regress stops, but beliefs are not justified.

- c) Intuitionism: The regress stops, but some beliefs are justified non-inferentially (directly known).

- d) Coherentism: The regress stops because some beliefs are justified as part of a coherent system of beliefs.

b)Skepticism

A skeptic would argue that although we may feel certain that something is morally right or wrong, we shouldn’t trust those feelings as evidence for knowing the truth. Feelings and experiences can be manipulated, and thus cannot serve as reliable foundations for knowledge.

The skeptic critiques other positions:

- Intuitionism: The idea that we know something is right (e.g., giving money to charity) because we simply believe it seems unconvincing. Belief alone doesn’t justify knowledge.

- Coherentism: If a belief is justified only because it fits into a coherent system, the skeptic asks, “Where does the justification come from?”

The skeptic’s argument is that moral beliefs are often inferred from other beliefs, but at the end of these inferences, there’s no further justification for the final belief. This lack of ultimate justification leaves moral beliefs “floating free” and unanchored.

If moral skepticism is correct, then we cannot know that actions like killing have the property of “wrongness,” making moral realism (the idea that moral facts exist independently of our beliefs) less attractive.

Revolutionary Fictionalism Already Happened?

Imagine a society adopts the framework of revolutionary fictionalism, where parents teach their children that moral beliefs are just fictional constructs. After generations of passing down this theory, could people eventually begin to see these fictions as truths?

If this is the case, how do we know that the revolution desired by revolutionary fictionalists hasn’t already occurred? Could it be that we already believe in morality as a fiction, but mistake it for truth?

A fictionalist might respond by saying that, unlike the proposed scenario, we don’t “pretend” to believe in morality—we actually believe in it. But this raises the question: what’s the difference between truly believing that “killing is wrong” and merely making-believe that “killing is wrong”?

Moral Fiction as a Pragmatic Choice

Now, consider a scenario where we discover that “Mars” is a fabrication, due to faulty equipment and calculations. Over time, society would likely stop talking about Mars, but few proponents of error theory would advocate for eliminating morality altogether. Most would argue that even if we recognize it as a fiction, we still gain something from maintaining moral beliefs.

One reason to entertain the fiction of morality is for coordinating actions. Terms like “ought” and “should” make it easier to coordinate behavior. Believing in morality might be more effective than eliminating it, as it helps people work together.

Another benefit of maintaining a moral fiction, rather than embracing eliminativism, can be seen in real-world examples. For instance, doctors report that more people are surviving gunshot wounds today, and one explanation is that people react to wounds as they’ve seen superheroes do in movies. This make-believe helps them believe they can survive more than they really can, which increases their chances of survival.

Similarly, when someone is trying to get fit, it’s more effective to frame their exercise regimen as an authoritative rule, like “I must run 10km every day.” This kind of make-believe can help them stay motivated and on track, even though they don’t have to run that distance. By treating certain actions as “right” or “wrong,” people can increase self-control and benefit from the structure that the moral fiction provides. This may be more effective than abandoning morality altogether.

References: