Identifying the Scan and Attack Infrastructures Behind Amplification DDoS Attacks

December 21, 2024 | 948 words | 5min read

Paper Title: Identifying the Scan and Attack Infrastructures Behind Amplification DDoS Attacks

Link to Paper: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2976749.2978293

Date: 24 October 2016

Paper Type: Internet, InfoSec, Cybersecurity, Attack-Paper, DNS, DDoS, DRDoS

Short Abstract:

Amplification DDoS attacks have become increasingly popular. In this paper, the author introduces a technique to uncover the infrastructure behind these attacks.

1. Introduction

In amplification attacks, an attacker spoofs the source IP address of requests sent to open Internet services like DNS, which then reflect the response packets to the victim. Thus, the attacker needs substantially fewer resources than the total reflected bandwidth.

Because attackers spoof their true identity, it is difficult to determine who they are. This is not the case in attacks like DoS. While IP traceback can be used to trace the origin of packets, this approach does not work in real-time and is very tedious.

The author introduces a new technique to establish the identity of an attacker by linking the reconnaissance phase, where the attacker scans for abusable amplifier services, with the attack phase, where the actual attack takes place. This method leverages the fact that during scanning, the attacker cannot spoof their IP address.

To establish this link, the authors create multiple honeypots that the attacker can abuse and select a subset of these honeypots for every attack, thereby encoding a secret identifier. When an attack is launched, they only need to check which honeypots were used to link the scan with the attack phase.

Importantly, their technique:

- Works in real-time.

- Does not require cooperation between ISPs.

- Provides a probabilistic guarantee and confidence level of accuracy.

2. Threat Model

The goal of an amplification attack is to render a system unusable by flooding the target’s network with a huge amount of traffic. To do this, an attacker uses amplifiers, which are internet-facing servers such as DNS or NTP.

In an attack, the attacker sends requests with a spoofed IP header to the innocent amplifier. The amplifier then amplifies the attack and sends its response toward the victim.

Amplification occurs because, in many cases, the response packet is much larger than the query packet. Many protocols are vulnerable to such attacks, with amplification factors ranging from 5 to 4000.

The attacker first needs to find amplifier servers, which is done via a scanner. While attackers could use botnets, empirical data suggests that most often, these attacks come from a single source.

3. Dataset

Their data was collected using the honeypot AMPPOT, which emulates a server offering UDP-based protocols vulnerable to amplification attacks.

The authors use the following definition for a DDoS attack: 100 consecutive packets from the same source without gaps longer than one hour.

Additionally, they obtained data from the creators of AMPPOT, who deployed honeypots in 2014.

4. Selective Response

Nowadays, it is possible to scan the entire IPv4 address space in a reasonable amount of time from a single machine. Thus, their basic assumption is that the attacker uses one machine for the scanning phase.

The idea is that every scanner will find a different unique subset of the deployed honeypots, which will uniquely identify them.

They achieve this by computing a hash over the source IP address combined with a secret hash. This hash is then used to generate a permutation of the honeypot set. The first \(N \cdot \alpha\) honeypots respond to a request, where \(N\) is the total number of honeypots and \(\alpha\) is the fraction of honeypots that should respond.

5. Attributing Attacks to Scans

5.1 Methodology

For every attack, they inspect the set of honeypots that were used. Empirically, over 95% of attacks use more than 4 honeypots, and 80% use at least 10 honeypots.

From this set of honeypots, they can then derive which scanner was used to detect them. This is done by maintaining an IP list at each honeypot, recording the IPs that discovered them, and then computing the intersection of these sets of IPs.

There are three possible scenarios:

Zero Candidates:

This occurs if an attacker uses data based on multiple scans or if an event is mistakenly identified as an attack.Exactly One Candidate:

They compute a confidence score to assess the likelihood that the identified scanner is responsible for the attack.More Than One Candidate:

This happens if an attacker uses too few honeypots during the attack.

The confidence score is calculated by determining the probability of falsely accusing a scanner of being responsible for an attack.

5.2 Results

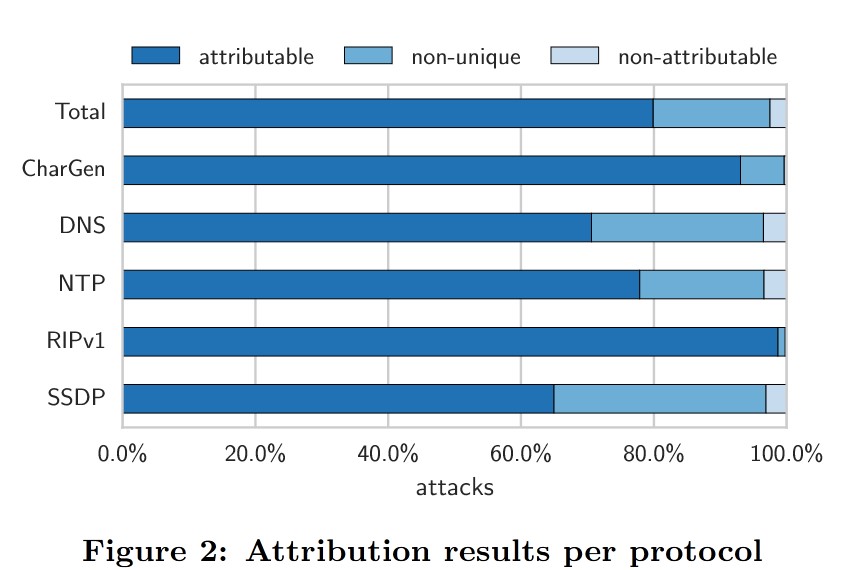

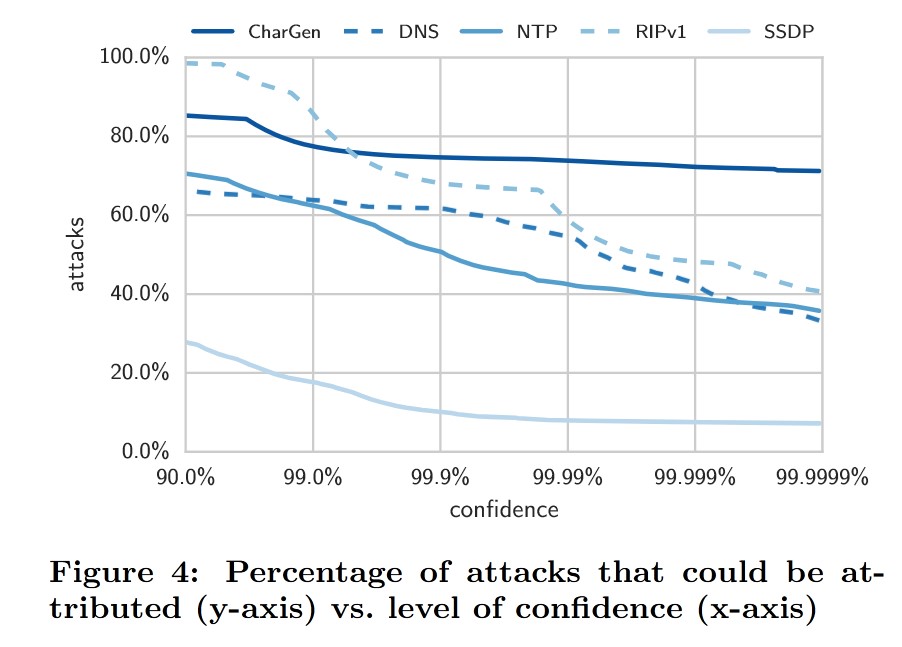

Out of 1,351,852 recorded attacks, 58% could be attributed with a confidence level of 99.9% or higher, and 47% could be attributed with a confidence level of 99.999% or higher.

6. Mapping Scan Infrastructure to Attacker Infrastructure

The main question: Are the systems used to perform scans also used to carry out subsequent attacks? Do attackers reuse their scanning infrastructure to launch attacks?

6.1 Methodology

Because of the spoofed IP addresses, it is difficult to determine the original packet source in amplification attacks.

To address this, the authors use the time-to-live (TTL) field in packet headers. The TTL is initially set to a high value when the packet is sent and is decremented with each hop. Thus, the difference between the initial TTL and the received TTL can be used to estimate the route length between the sender and receiver.

However, the authors do not have access to the sender’s initial TTL value. Instead, they observe packet traffic from multiple points in the network using their honeypots. This allows them to measure the path length between the honeypots and the packet origin. By hypothesizing that packets from the same source will have similar hop distances, they can approximate the packet origin.

7. Conclusion

Use this against, script kiddos!