Towards Temporal Information Processing – Printed Neuromorphic Circuits with Learnable Filters

September 29, 2025 | 993 words | 5min read

Paper Title: Towards Temporal Information Processing – Printed Neuromorphic Circuits with Learnable Filters

Link to Paper: https://dl.acm.org/doi/fullHtml/10.1145/3611315.3633249

Date: Dec. 2023

Paper Type: printed electronics, neuromorphic computing, temporal information processing, recurrent neural network

Short Abstract: The paper proposes a printed temporal processing block that combines existing printed neuromorphic circuits with learnable filters.

1. Introduction

The number of devices in the Internet of Things (IoT) has grown rapidly, and for next-generation electronics such as smart labels, smart band-aids, and smart packaging, flexible, low-cost, and efficient technology is needed.

Silicon-based electronics made by lithography often consume too much power, are expensive to develop, have high costs, and are not flexible.

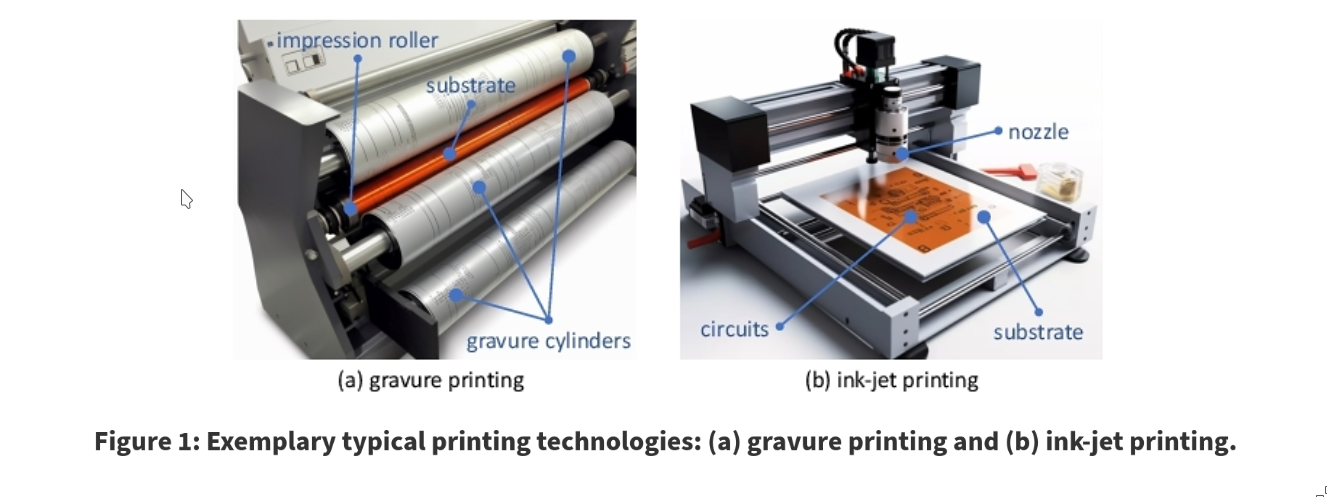

One prominent alternative to lithography is printed electronics (PE), which works similarly to color printing and allows for significantly reduced manufacturing costs, as well as flexibility with materials to achieve properties such as softness or biodegradability. The main disadvantage of PE is that it produces larger feature sizes—for example, printable transistors are larger than those made by lithography.

Furthermore, PE has good synergy with neuromorphic circuits, which compute using analog signals instead of digital. This removes the need for analog-to-digital converters (ADCs), reducing device count and improving power efficiency.

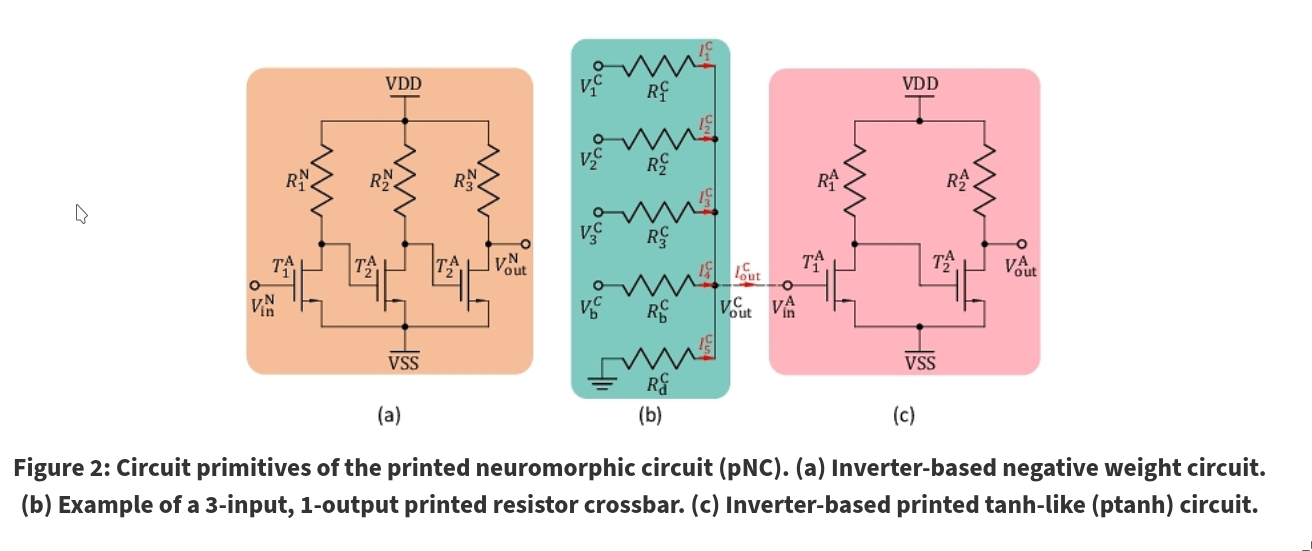

The idea in neuromorphic computing is to design analog circuits that emulate artificial neural networks (ANNs). This is typically achieved by using resistor crossbars for weighted-sum operations and nonlinear transfer circuits for tanh activation functions.

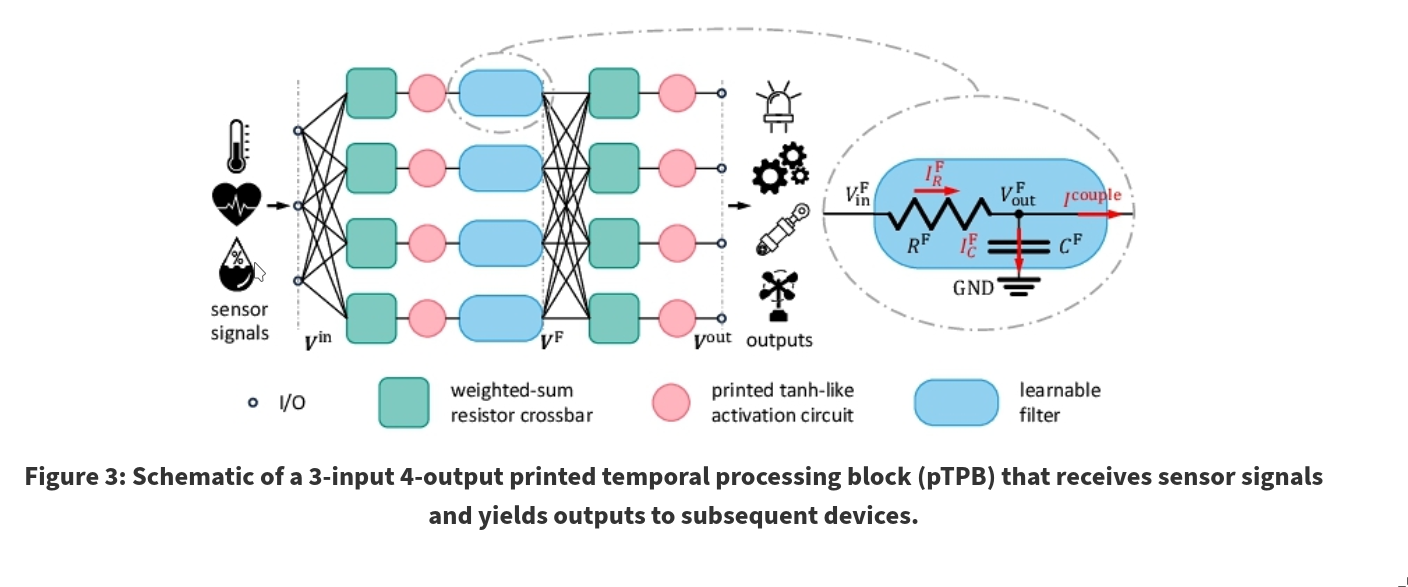

In this paper, the authors propose a learnable and tunable printed temporal processing block (pTPB) by introducing a capacitor capable of memorizing information from previous inputs. Thus, the circuit no longer depends only on the current signal but also on all previous time steps. They then combine the pTPB with printed neuromorphic circuits (pNCs) to create printed temporal processing neuromorphic circuits (pTPNCs), which are capable of processing time-series sensory inputs.

2. Background

2.1 Printed Electronics

Printed electronics (PE) is an additive manufacturing process that works by depositing functional inks onto a substrate. In contrast to lithography, it is lower in cost because the required equipment and process are less complex.

Since PE results in larger feature sizes, it cannot replace silicon-based lithography. Instead, it is used for edge-computing devices such as disposable or wearable electronics—cheap, low-power devices.

Most PE uses P-type transistors, which require a supply voltage above 25V. This is unsuitable for low-power devices, where N-type transistors are needed, as they can operate below 1V.

2.2 Printed Analog Neuromorphic Circuits

Resistor crossbars emulate weighted-sum operations used in ANNs:

$$ V_{out} = \sum \frac{g_i}{G} V_i + \frac{g_i}{G} $$where \(G\) is the sum of conductances in the crossbar and \(g = 1/R\).

By appropriately designing and printing the conductances, desired weights and biases can be achieved. Importantly, weights are limited to being less than 1 and positive because resistances can only be positive. To achieve negative values for weights or biases, inverter-based negative-weight circuits are required.

A printed tanh-like circuit is used as a nonlinear activation function in ANNs:

$$ V_{out} = ptanh(V_{in}) $$2.3 Recurrent Neural Networks

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are primarily used to handle variable-length input sequences, whereas MLPs require fixed input sizes. A general formulation of an RNN is:

$$ h_k = f_1(f_2(h_{k-1} + f_3(x_k))) $$$$ y_k = f_4(h_k) $$The choice of functions \(f_i\) depends on the architecture. For example, \(f_2, f_3\) can be weighted sums, while \(f_1, f_4\) can be tanh operations.

3. Printed Temporal Processing Block

To enable circuits to memorize and process temporal data, the authors introduce printed temporal processing blocks (pTPBs). By stacking multiple pTPBs, more sophisticated functions can be realized.

Depending on the application, different behaviors of the pTPB are needed; therefore, each block has weights that can be learned.

3.1 Modeling of the Temporal Processing Unit

A pTPB consists of multiple Temporal Processing Units (TPUs), represented by the blue boxes in the figure.

They can be modeled as:

$$ V_{out} = \beta V_{out}^{k-1} + (1 - \beta) V_{in}^k $$where \(\beta\) depends on the resistor \(R^F\) and capacitor \(C^F\). By adjusting these, the filtering behavior can be learned—making them the physical representation of weights. These units are referred to as learnable filters.

3.2 Modeling of the Temporal Processing Block

The input voltages are first passed through the resistor crossbar, followed by tanh activation circuits, and then fed into the filters.

Mathematically, a pTPB can be described as:

$$ \mathbf{V}*k^{\mathrm{F}} = \beta' \odot \mathbf{V}*{k-1}^{\mathrm{F}} + (1 - \beta') \odot \mathrm{ptanh}(\mathbf{W}_1 \mathbf{V}_k^{\mathrm{in}} + \mathbf{b}_1), $$$$ \mathbf{V}_k^{\mathrm{out}} = \mathrm{ptanh}(\mathbf{W}_2 \mathbf{V}_k^{\mathrm{F}} + \mathbf{b}_2), $$This circuit represents an instance of an RNN, where \(f_1, f_2\) are identity functions, and \(f_3, f_4\) are weighted-sum operations followed by activation functions.

Notably, a pTPNC may consist of multiple pTPBs connected successively to accomplish more complex computational tasks.

3.3 Training of pTPNCs

The cross-entropy loss \(L(\cdot)\) can be minimized with respect to the crossbar conductances \(g\) to reduce the mismatch between the label \(y\) and the circuit prediction \(\hat{y}(g, x)\) for an input \(x\), thus improving classification accuracy.

4. Evaluation

4.1 Experimental Setup

Dataset:

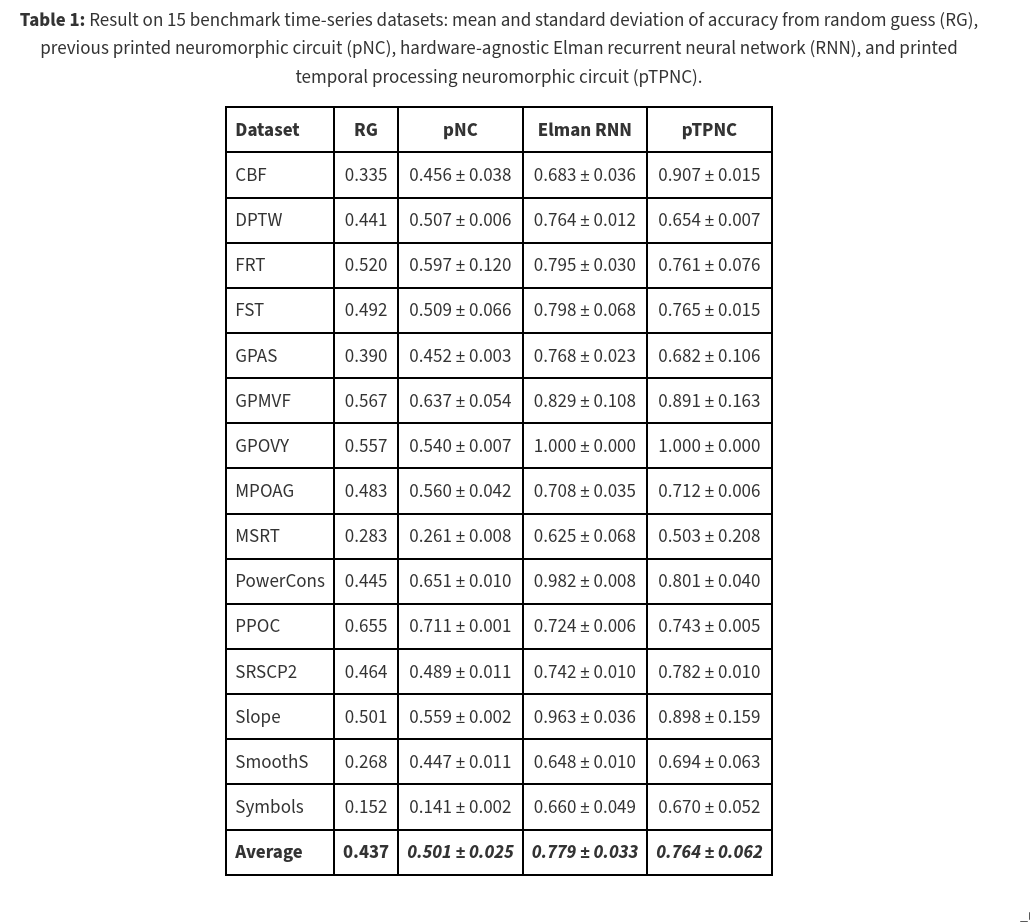

- Datasets from the UCR time-series classification archive

- Filtered based on complexity

- Only datasets with \(N_{in}\) and \(N_{out}\) below 10 were kept

- Preprocessed by resizing all series lengths to 128

- Normalized to the range [−1, 1]

- Split into training (60%), validation (20%), and test (20%) sets

- Used 2-layer RNNs as baseline models

Training setup:

- Each dataset used a 2-layer pTPNC (two stacked pTPBs)

- Objective minimized using the Adam optimizer with default parameters

- Initial learning rate: 0.1, halved after 100-epoch patience

- Training repeated 10 times with random seeds 0–9

Baselines:

- Compared against 2-layer pNCs without pTPBs

- Compared against RNNs, which pTPNCs aim to mimic

Evaluation:

- Selected the top 3 models (from different seeds) for each dataset

- Evaluated on test sets

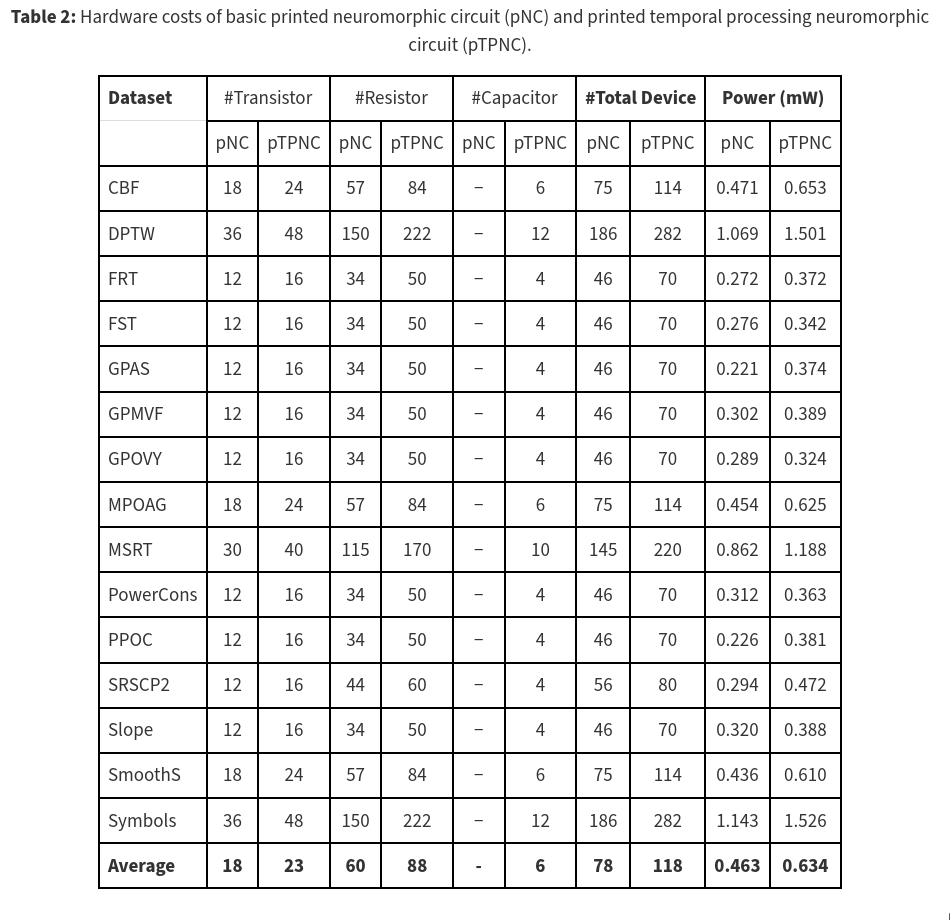

- Measured additional hardware resources required by the new circuit design

- Collected device counts and total power consumption compared to pNCs

4.2 Results

5. Conclusion

By incorporating temporal information into the neural network, pTPNCs can handle time-series data while requiring only 1.5× more devices and consuming 1.3× more power compared to basic pNCs.