Losing Control of the Internet: Using the Data Plane to Attack the Control Plane

December 11, 2024 | 1,549 words | 8min read

Paper Title: Losing Control of the Internet: Using the Data Plane to Attack the Control Plane

Link to Paper: https://www-users.cse.umn.edu/~hoppernj/lci-ndss.pdf

Date Published: 04. October 2010

Paper Type: InfoSec, Internet, Cybersecurity, Resilience, Topology

Short Abstract:

The author introduces an attack called CXPST, which is a distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack targeting the control plane of the internet by leveraging the data plane.

1. Introduction

The internet consists of two main components:

- The data plane, which forwards packets to their destination.

- The control plane, which determines the path to the destination.

The control plane is designed to route around local failures, such as when a link is severed or a router fails. However, this resilience also creates a vulnerability: local failures can have a global impact.

The CXPST attack exploits this weakness by causing local failures that lead to global instability. It achieves local disruption by attacking BGP (Border Gateway Protocol) sessions between routers. This is done using a method described by Zhang et al., known as ZMV, which exploits the fact that the control plane and data plane share the same physical medium. By leveraging ZMV, attackers can trick BGP speakers into believing that BGP sessions have failed, triggering global BGP updates.

CXPST carefully selects the location and timing of the attack to overwhelm the computational capacities of routers with excessive BGP updates. Remarkably, it only targets a small number of links, significantly reducing the bandwidth required for such an attack.

Simulations show that a botnet with 250,000 members is sufficient to severely disrupt the internet’s control plane.

2. Background

2.1 BGP

The internet consists of multiple smaller networks called autonomous systems (ASes). ASes vary widely in size and in the number of connections they have to other ASes.

We differentiate between:

- Core ASes, which have a high degree of connectivity to other ASes.

- Fringe ASes, which have a low degree of connectivity to other ASes.

Core ASes agree to transit traffic on behalf of fringe ASes to other ASes.

To determine the best route for a packet, routers exchange messages to communicate which systems they can reach. This is achieved using the path-vector routing algorithm, implemented in the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP). Routers located between two ASes are called border routers.

Each border router maintains its own routing table. When a router updates its routing table due to an event—such as a network cable being severed—it informs all neighboring ASes of the change. Routers within these ASes can then propagate the update even further.

2.2 BGP Stability

Under normal circumstances, the BGP algorithm converges to a stable state, meaning all routers share consistent routing information.

When failures occur, such as hardware malfunctions, routing paths must be recalculated and re-advertised to other routers, which in turn propagate these updates further. This can cause BGP updates to spread globally.

During the time it takes to recalculate routes, packets may still be sent along outdated paths, leading to packet loss.

If a router oscillates between availability and unavailability, this is referred to as route flapping. Such behavior can result from misconfigurations and causes an enormous number of BGP messages to be exchanged, placing significant strain on routers.

To mitigate these issues, several countermeasures exist:

- Minimum route advertisement intervals: Prevents a series of rapid advertisements.

- BGP graceful shutdown: Introduces a grace period after a router becomes available again before it can share routing updates.

2.3 Attacks on BGP Routers

Many attacks target BGP routers. One such attack, proposed by Zhang, Mao, and Wang (ZMV), tricks a pair of routers into disconnecting from each other. An unprivileged attacker interacts with the control plane via the data plane, exploiting the fact that they share the same physical medium.

The BGP protocol uses a hold timer to determine whether two routers are connected. If two routers fail to communicate within the hold timer’s duration, they assume the connection is down.

An adversary can exploit this by flooding the data plane, causing messages from the control plane to be dropped. This results in a “digitally severed” connection between the routers.

3. The CXPST Attack

3.1 Attacker Model

There are existing attacks that exploit BGP speakers to target the control plane. However, in this attack, the authors propose an alternative approach using an unprivileged adversary—i.e., the attacker does not control a BGP speaker.

Specifically, the attacker operates a botnet of a reasonable size, which they use to generate network traffic.

3.2 CXPST Concept

The attacker uses the ZMV attack to create instability in the control plane. This is achieved by disrupting the data plane, forcing routes to be recalculated and overwhelming the routers.

After disrupting a link, the attacker temporarily halts the attack, allowing BGP routers to communicate again and generate BGP update messages.

The botnet then re-targets the same link, severing the connection once more.

This cycle repeats, causing the link to oscillate between availability and unavailability, thereby inducing route flapping.

While the routers directly connected to the targeted link are most affected, others are impacted as well due to the propagation of BGP updates.

Thus, by creating a few localized failures, the attack achieves a nearly global impact, overwhelming the computational capacity of many routers on the internet.

For this attack to succeed:

- The attacker must select appropriate targets.

- The attacker must direct traffic to these targets.

- The impact of existing defense mechanisms must be minimized.

3.3 Target Selection

To select appropriate targets, the concept of BGP edge betweenness can be used:

where \( path_{st}(e) \) is the number of BGP paths between IP blocks \( s \) and \( t \) that traverse the edge \( e \).

The attacker can approximate this value by performing traceroute from bots in the botnet to other nodes in the network and aggregating the results.

3.4 Addressing Load Balancing

Load balancing can pose a challenge for the CXPST attack. To identify and exclude links with load balancing, the attacker can:

- Perform

traceroutemultiple times. - Check if links in the route change across different attempts.

If changes are observed, the attacker concludes that the link is part of a load-balancing configuration and excludes it from the list of potential targets.

3.5 Attack Traffic Management

Using all bots in the botnet to send traffic to the target could inadvertently overload non-targeted links that transport the traffic, effectively creating additional, unintended DDoS attacks.

To avoid saturating unrelated links, the following measures are employed:

- Ensure that each selected path contains the targeted link.

- Verify that paths do not include other links targeted by other bot sets.

- Send slightly more traffic than necessary as a “safety net” in case some traffic is diverted.

3.6 Selecting Bots for the Attack

To efficiently allocate bots:

- Construct two flow networks based on

traceroute:- In the first network, bots are the sources, and target links are the sinks.

- In the second network, target links are the sources, and the destination network is the sink.

- Run a max-flow algorithm on the first network to determine which bots to use.

- Use the second network to analyze the destinations to which traffic should be directed.

When feasible, traffic can be routed from one bot to another to mimic legitimate traffic. This increases the likelihood of the traffic being perceived as “wanted” by the target.

4. Mitigating Defenses

Existing BGP defense mechanisms are generally ineffective against the CXPST attack:

- Graceful restart and minimum route advertisement intervals were not designed to address this type of attack.

- Route damping can mitigate the attack, but the attacker can periodically check if a link has been dampened and temporarily stop targeting it until it becomes vulnerable again.

5. Simulations

To evaluate the impact of their attack, the authors conducted simulations using empirical datasets that measured parts of the internet’s topology. These datasets were used to model the simulated network.

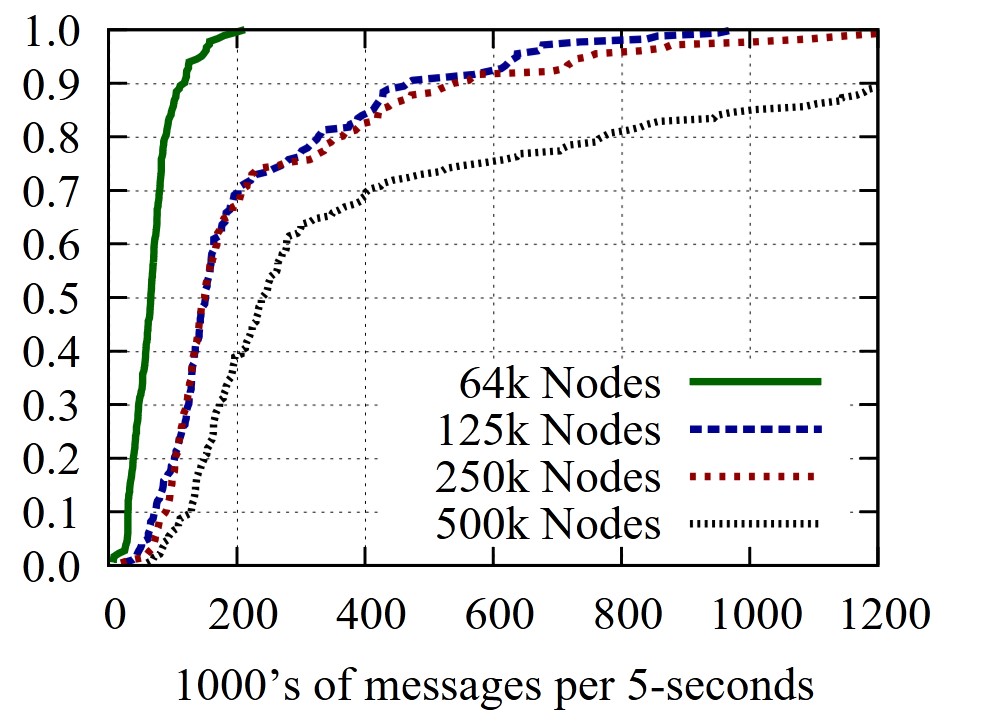

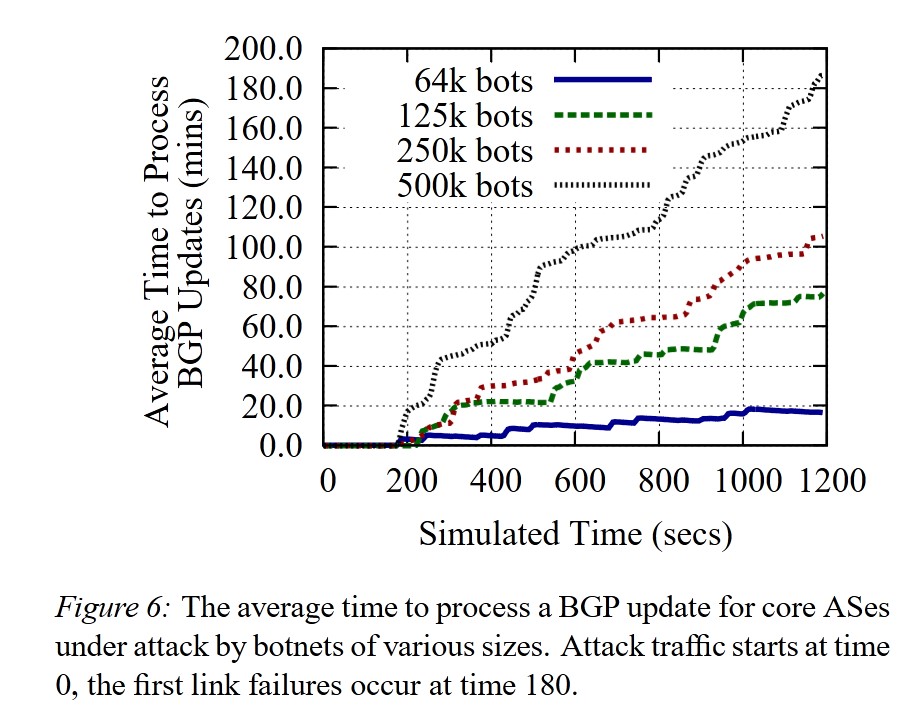

The compromised nodes in the botnet were distributed based on recent research. Botnets of various sizes were tested, including 64,000, 125,000, 250,000, and 500,000 nodes. However, after 250,000 nodes, diminishing returns were observed, making further increases less effective.

6. Results

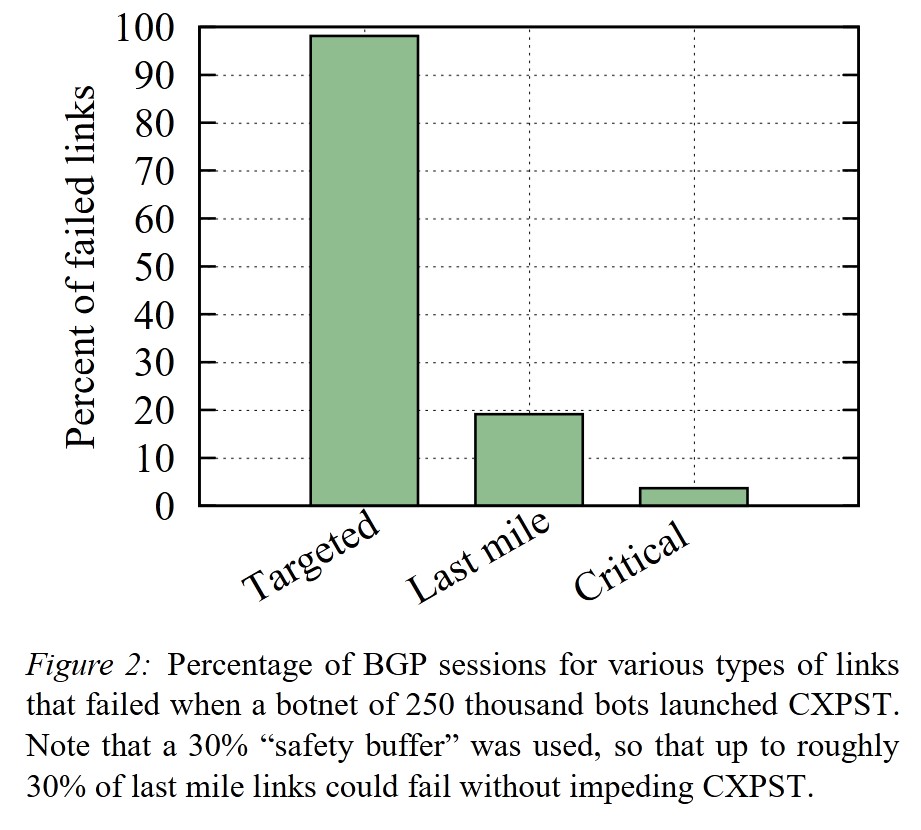

The authors categorized links into the following types:

- Targeted links: Links directly attacked by the botnet.

- Last mile: Links not directly targeted, connecting fringe ASes to the network.

- Transit: All other links.

Using a botnet of 250,000 nodes, 98% of the targeted links were successfully disrupted, while only 19% of non-targeted links experienced disruption.

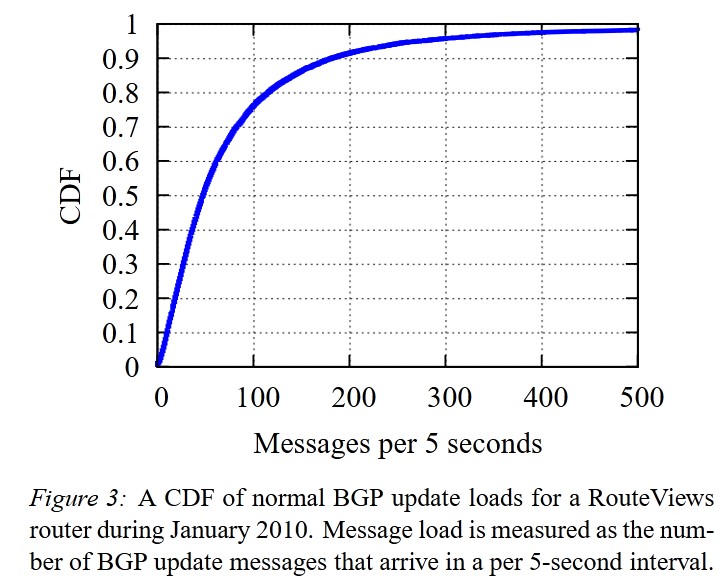

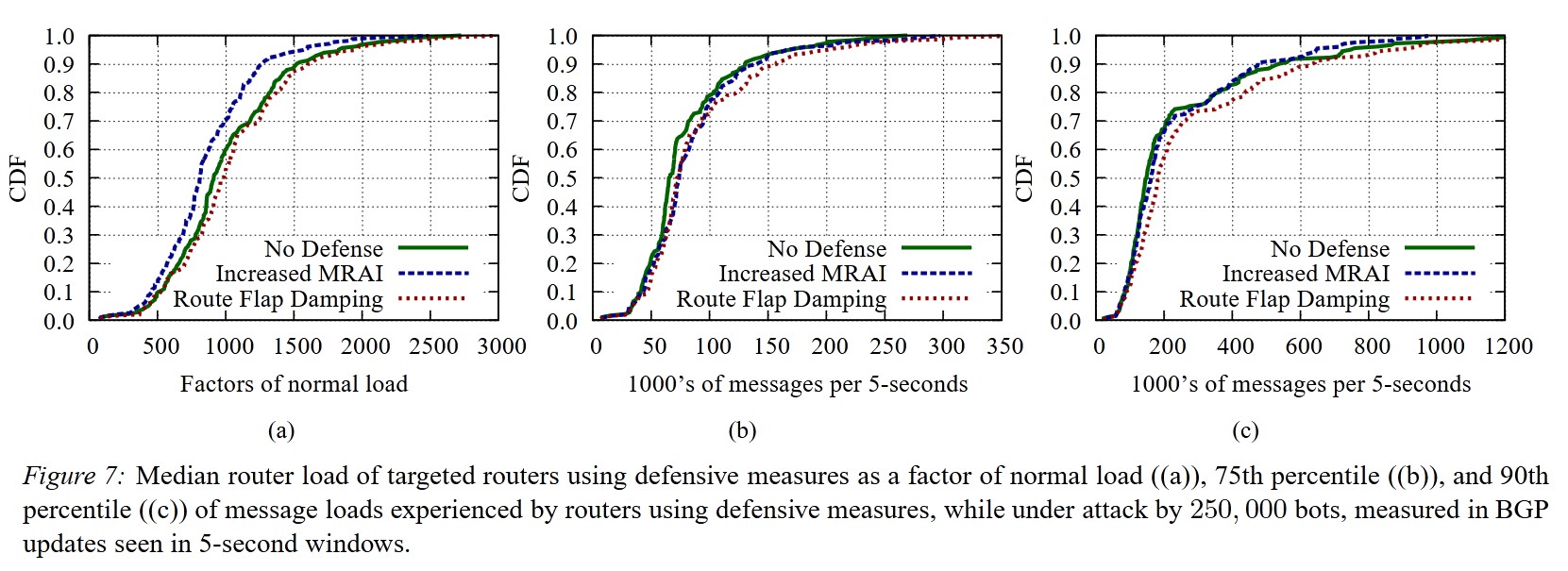

The simulations demonstrated that the attack successfully generated bursts of BGP update messages. For example, during normal operation, the 90th percentile load was 182 messages every 5 seconds. During the attack, this load dramatically increased for the targeted routers.

After 10 minutes of attack using 250,000 nodes, the backlog of BGP updates became large enough to delay processing for 45 minutes.

As previously mentioned, existing defense mechanisms had minimal impact on mitigating the attack’s effectiveness.

6. Attack Prevention

The attack can be effectively mitigated by disabling the mechanisms that enable it. One simple approach is to disable the hold timer functionality in routers.

By doing this, BGP sessions will not terminate due to high traffic levels in the data plane. The authors estimate that if 50% of ASes implemented this change, it would be sufficient to completely stop the CXPST attack.