- Groundhog Day (1993)

Cute Movie. 7/10

- Decay

- Confessions (Augustine)

This is basically the first ever written autobiography. Written by Saint Augustine around 400 AD, it follows his life from birth through his teenage years into adulthood, while also tracing his spiritual journey. Beginning as someone educated in Greek literature, moving through the heretical Christian sect of Manichaeism, and finally culminating in his conversion to Christianity.

The book is beautifully written. It is especially impressive how he interweaves his own reflections with quotations from the Bible, which appear throughout the text. I would say Book 8 is the most beautiful, while the last two books are the most philosophical, dealing with the nature of time and offering an interpretation of Genesis. It is also striking how many times I thought, “Wow, this question is still relevant today.” For example, Augustine’s struggle with the nature of time could easily come straight out of philosophical papers from the 1980s.

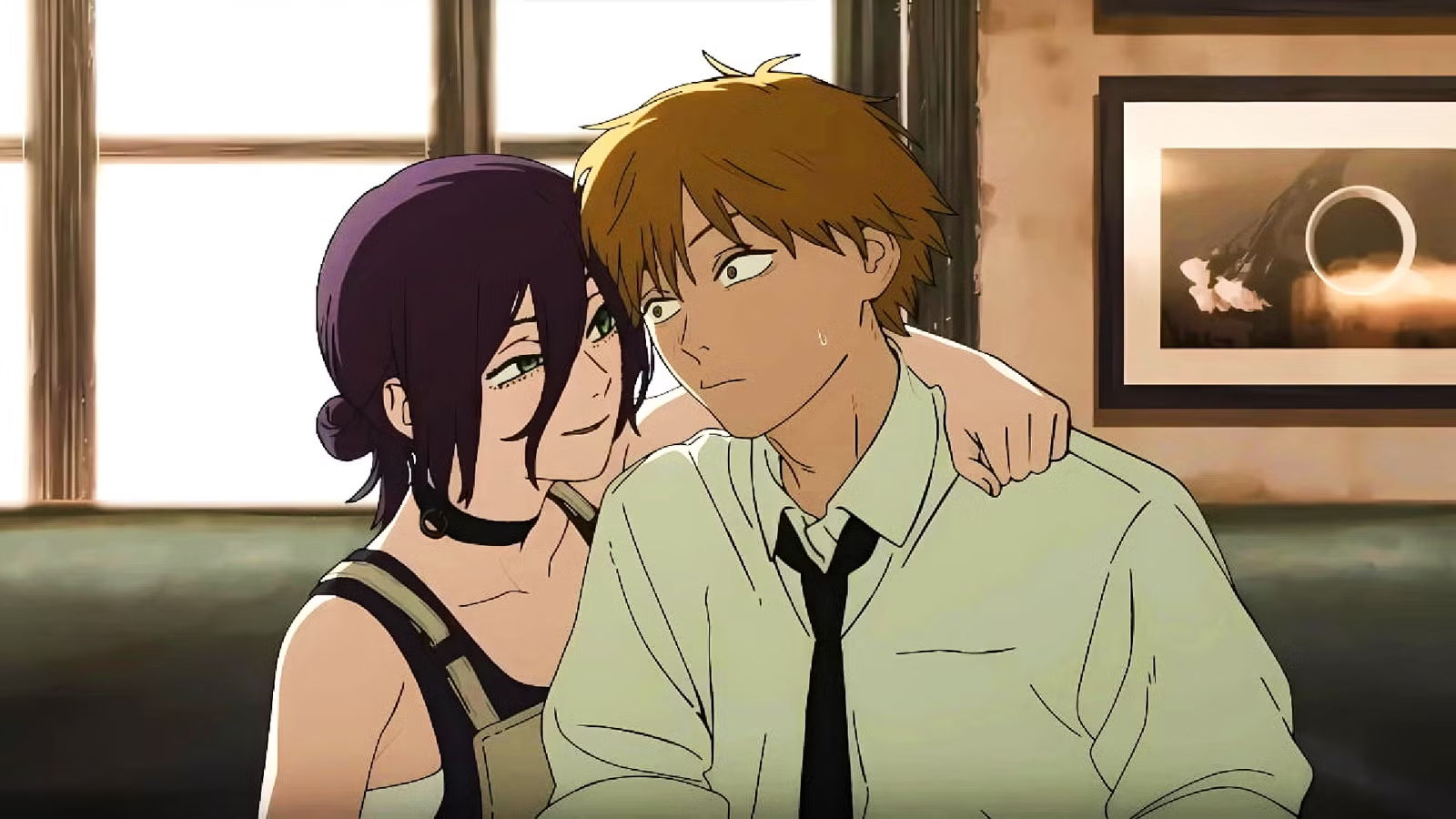

- Chainsaw Man - Reze Arc (2025)

Absolutely gorgeous movie. So pretty, every frame a painting. Very impressive action scenes too. I was also slightly disappointed that we saw so little of Power.

There is one critique I have: I think the arc works really well in the anime, where you’re already familiar with the characters. Because the beginning of the movie is rather slice-of-life, the hook is missing. This works better in the anime, where you already know the characters and just like seeing them interact. However, I think it would have been better if there had been a stronger hook at the beginning. Though I have to admit, I’m not sure how that could have been done without giving away what is later revealed.

I loved the post-credit scene. Power forever. 8/10

- Augustine on what was before God

See how full of old errors are those who say to us: ‘What was God doing before he made heaven and earth? If he was unoccupied’, they say, ‘and doing nothing, why does he not always remain the same for ever, just as before creation he abstained from work? […]

This is my reply to anyone who asks: ‘What was God doing before he made heaven and earth?’ […] I say that you, our God, are the Creator of every created being, and assuming that by ‘heaven and earth’ is meant every created thing I boldly declare: Before God made heaven and earth, he was not making anything. […]

If, however, someone’s mind is flitting and wandering over images of past times, and is astonished that you, all powerful, all creating, and all sustaining God, artificer of heaven and earth, abstained for unnumbered ages from this work before you actually made it, he should wake up and take note that his surprise rests on a mistake. […]

You have made time itself. Time could not elapse before you made time. […]

It is not in time that you precede times. Otherwise you would not precede all times. In the sublimity of an eternity which is always in the present, you are before all things past and transcend all things future, because they are still to come, and when they have come they are past. ‘But you are the same and your years do not fail’ (Ps. 101: 28). Your ‘years’ neither go nor come. Ours come and go so that all may come in succession. All your ‘years’ subsist in simultaneity, because they do not change; those going away are not thrust out by those coming in. But the years which are ours will not all be until all years have ceased to be. Your ‘years’ are ‘one day’ (Ps. 89: 4; 2 Pet. 3: 8), and your ‘day’ is not any and every day but Today, because your Today does not yield to a tomorrow, nor did it follow on a yesterday. Your Today is eternity. So you begat one coeternal with you, to whom you said: ‘Today I have begotten you’ (Ps. 2: 7; Heb. 5: 5). You created all times and you exist before all times. Nor was there any time when time did not exist.

There was therefore no time when you had not made something, because you made time itself. No times are coeternal with you since you are permanent. If they were permanent, they would not be times.

~ Confession, XI (12, 14-17)

I2P

I2P