The Cynic Philosophers: From Diogenes to Julian

June 9, 2025

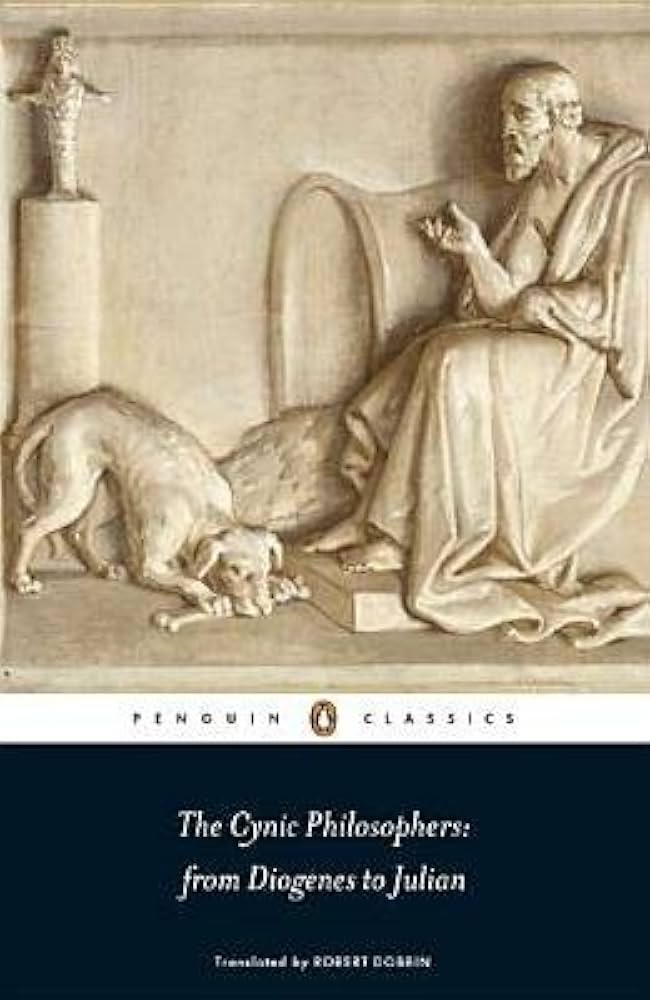

The book The Cynic Philosophers: From Diogenes to Julian is a collection of writings by various Cynic thinkers, starting in ancient Greece with Diogenes and ending in the imperial Roman period with Emperor Julian. You can think of it as a compilation of short essays and fragments—no single chapter or text takes more than 30 minutes to read. This makes it perfect for picking up occasionally, reading a passage, and setting it down again. Perhaps due to it being a Penguin translation, it’s also very readable and accessible.

It should be clarified that when I refer to Cynicism, I mean the original philosophical doctrine, not the modern sense of the word, which implies pessimism or distrust. The ancient Cynics can be thought of as a more extreme form of Stoicism. The Stoics taught that we should be indifferent to anything outside our control—such as wealth, fame, or power. This meant that we shouldn’t reject such things if they come to us, but we also shouldn’t actively pursue them.

The Cynics were more radical. They believed that the only truly good thing is virtue—something fully within our control—and that everything else is bad or distracting. As a result, they rejected all forms of wealth and worldly power. They lived on the streets and, following the example of their founder Diogenes, adopted his iconic image: a simple cloak and a walking stick. They were famous for their public displays of defiance against social norms—such as defecating and masturbating in public—and, like Socrates, they roamed the city provoking people to reflect on their lives.

The reasoning behind these outrageous public acts was twofold. First, they aimed to provoke people into questioning commonly accepted values, much like how Plato’s dialogues often end in aporia, a state of philosophical puzzlement. Second, their acts had a performative aspect: by doing something shocking, they intended to act as beacons for others—if they could challenge societal norms so radically, maybe you could change a few small things in your own life. Only by truly understanding the rules can breaking them be meaningful. The Cynics didn’t reject social convention out of laziness or rebellion for its own sake; they were deliberate and principled in their actions.

Because Cynicism was deeply rooted in Greek mythological and philosophical traditions (with Heracles being an ideal figure), it eventually faded with the death of Emperor Julian, the last pagan emperor of Rome. Even during his time, Julian criticized the Cynics for having strayed from their original path and becoming diluted. That said, one could argue that Cynicism and its spirit of asceticism were adopted by Christianity—first through figures like Jesus (who may or may not have had direct exposure to Cynicism) advocating a life of poverty in service to God, and later through Christian hermits like the Stylites.

If I have one criticism of the Cynics, it’s that they seem to have traded the philosophical rigor of their counterparts—the Stoics, and even Socrates—for a more witty, performative approach. The book is full of clever one-liners describing how Cynics reacted to various situations, but it lacks in-depth philosophical argument. However, this can be explained by the fact that Cynics replaced theoretical rigor with a philosophy of action. If the philosopher’s task is to know oneself, then for the Cynics, that meant acting in accordance with virtue rather than engaging in abstract metaphysics. They preferred to embody their values directly in the world.

Accordingly we must go back to the divisions of the Cynic philosophy. For the Cynics also seem to have thought that there were two branches of philosophy, as did Aristotle and Plato, namely speculative and practical, evidently because they had observed and understood that man is by nature suited both to action and to the pursuit of knowledge. And though they avoided the study of natural philosophy, that does not affect the argument. For Socrates and many others also, as we know, devoted themselves to speculation, but it was solely for practical ends. For they thought that even self-knowledge meant learning precisely what must be assigned to the soul, and what to the body. And to the soul they naturally assigned supremacy, and to the body subjection. This seems to be the reason why they practised virtue, self-control, modesty and freedom, and why they shunned all forms of envy, cowardice and superstition.

~ To the uneducated Cynics

My favorite story about the Cynics involves Zeno, who became a pupil of Crates of Thebes—the second most influential Cynic after Diogenes. But Zeno couldn’t bear the constant public humiliation that came with Crates’ lifestyle.

Crates, desirous of curing this defect in him, gave him a potful of lentil soup to carry through the Ceramicus (the pottery district); and when he saw that Zeno was ashamed and tried to keep it out of sight, Crates broke the pot with a blow of his staff. As Zeno began to run off in embarrassment with the lentil soup flowing down his legs, Crates chided, “Why run away, my little Phoenician? Nothing terrible has befallen you.”

Zeno was so embarrassed that he went on to found his own school of philosophy—Stoicism. He eliminated the public displays of defiance and chose a more disciplined, internalized form of virtue. In hindsight, this may have been for the better, considering how influential his philosophy became.

In modernity, cynicism is referenced through Nietzsche in his work The Gay Science, particularly in the aphorism “The Madman.” It depicts a man walking around during the day with a lamp, asking, “Where is God?”—a metaphor for the death of God. This image is a reference to:

When asked why he went about with a lamp in broad daylight, Diogenes confessed, “I am looking for an honest man.”

~ Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Book VI, section 41