- Coherence (2014)

Stream of consciousness, ending spoiler: What a garbage movie. Amateurish acting, shit cinematography, no cool visuals. Shot like a cheap horror movie: oh look, even the classic eerie music is there, hooray. Also, we’re in a horror movie, so let’s all separate and go our separate ways; this won’t go wrong, surely.

The whole movie being set in an American diner is cliché, and so are all the characters. It uses pseudo-science for a mystery plot. I don’t care about the mystery and don’t get why anybody would care about that. What do people in other realities have to do with me? Everyone acts hysterical, and the movie insists upon itself. It takes itself so seriously for all the bullshit it peddles. Multiple times my eyes physically rolled in their sockets.

Finally, the ending was shit. Actions should have consequences. She killed a person and then woke up like it never happened, nice deus ex machina. She should have had to live with the consequences and be confronted with them. Then the movie would have at least had a learnable lesson to teach. As it is, it’s just a movie with a shitty mystery plot.

I guess the movie might be good if you like mystery plots, but don’t expect more than that.

When the line came:

“If there are a million different realities, don’t you realize what this means? I have slept with your wife in every one of them.”

I finally understood what this movie was about: the entire movie was ragebait. One big joke. I wasted my time on this, thank you. 4/10

- Sleep

The burden of the world weighed me down with a sweet drowsiness such as commonly occurs during sleep. The thoughts with which I meditated about you were like the efforts of those who would like to get up but are overcome by deep sleep and sink back again. No one wants to be asleep all the time, and the sane judgement of everyone judges it better to be awake. Yet often a man defers shaking off sleep when his limbs are heavy with slumber. Although displeased with himself he is glad to take a bit longer, even when the time to get up has arrived. In this kind of way I was sure it was better for me to render myself up to your love than to surrender to my own cupidity. But while the former course was pleasant to think about and had my notional assent, the latter was more pleasant and overcame me. I had no answer to make to you when you said to me ‘Arise, you who are asleep, rise from the dead, and Christ shall give you light’ (Eph. 5: 14). Though at every point you showed that what you were saying was true, yet I, convinced by that truth, had no answer to give you except merely slow and sleepy words: ‘At once’—‘But presendy’—‘Just a little longer, please’. But ‘At once, at once’ never came to the point of decision, and ‘Just a little longer, please’ went on and on for a long while. In vain I ‘delighted in your law in respect of the inward man; but another law in my members fought against the law of my mind and led me captive in the law of sin which was in my members’ (Rom. 7: 22). The law of sin is the violence of habit by which even the unwilling mind is dragged down and held, as it deserves to be, since by its own choice it slipped into the habit. ‘Wretched man that I was, who would deliver me from this body of death other than your grace through Jesus Christ our Lord?’ (Rom. 7: 24–5).

~ Confession, VIII (12)

- In die Sonne Schauen (2025)

At my university there is a film group that regularly shows movies. Today they showed “In die Sonne schauen.” I looked up some information on it beforehand and it intrigued me, so I decided to watch it.

The movie is rather long and it also feels slow. Further, the film focuses on the darker sides of being human: for example, close-up shots of flies, dead people, and amputation.

This also raises the question of how to understand the movie. I do not think it makes much sense to force a coherent interpretive narrative onto it. Rather, it should be viewed as a series of thematic impressions that fit together and paint a picture, but a picture that remains abstract instead of clear and graspable. In other words, Nietzsche would say this movie is Dionysian instead of Apollonian.

As I already stated, I do not think there is a coherent thematic narrative one can extract from this film, but there are certainly themes in it that I want to describe. The movie is best understood as a set of dichotomies:

- Coldness of death vs. warmth of life: Throughout the movie there are multiple scenes in which a character in the midst of life describes it as warm—be it the sand and stones on the beach or a penis being touched. This is contrasted with the lifeless coldness of death, shown through the dead deer or the dead grandmother.

- Unimportant sensual experiences vs. important memories: Another dichotomy concerns sensual experiences that seem trivial and unimportant, yet are direct and memorable, like the smell of water or fresh-cut grass, and can be recalled vividly. This is contrasted with important memories of loved ones, such as the dead grandmother, whose exact face we can no longer remember. In the movie, this is depicted by heavy bloom and film grain when a character remembers something, contrasted with the non-grain, non-bloom of direct life.

- Youth full of life vs. the wish for death: The film plays across multiple time periods in each of which young women are the focus, and in each period the youngest has a yearning for death. We thus have the contrast between a person full of life who simultaneously wishes to be close to death.

- Sexuality against women vs. sexuality from women: Another theme is sexual violence against women contrasted with sexuality coming from women themselves. For examle in one scene a maid is basically sold into sexual servitude or an older man stares at a young girl. This is contrasted with sexuality initiated by women, particularly in the modern time period and the one from the DDR period.

- Physical death vs. metaphorical death: Another contrast is physical death, depicted in the dead grandmother, the dead boy, the dead deer, versus a more metaphorical death. Many characters who have a death wish describe themselves as not knowing who they are. By acting and imitating the behavior of those around them, they forget who they are; even their own names sound strange to them. In a sense, these characters, by becoming so much like the ones they emulate, are already dead. They have killed themselves in the process. This fits well with their death wishes, the girl who wants to stop her heartbeat, or the younger girl who tries to drown herself. Subconsciously they know that they are already dead, and their bodies simply continue doing what they are supposed to do.

- Not controlling the body vs. controlling the body: This brings me to the final contrast. Throughout the movie there are characters who are not in control of their bodies: the mother who can only laugh when something sad happens, the woman who constantly gags because her stomach acts on its own, or the woman who loses the ability to walk even though her legs work perfectly fine. In all these cases the conscious mind cannot control something more unconscious. This ties into the previous contrast: they know they are already dead, and their bodies also want to die.

What irritates me about this movie, especially compared to other films that are meant to be interpreted more metaphorically than literally, like Angel’s Egg or No Country for Old Men, is that whereas those films both describe a problem (in Angel’s Egg it is faith; in No Country for Old Men it is evil), they also provide at least the beginning of attempts at solutions (Angel’s Egg: accepting or rejecting faith; No Country for Old Men: accepting evil, fighting evil, or refusing to care). This movie does not build anything. It asks questions and shows contrasts but does not even provide the beginnings of answers.

Perhaps instead of viewing this movie as an archetypal myth in the Nietzschean sense, it makes more sense to view it as a purely Dionysian depiction of aspects of the human condition.

Mom somehow never knew when to laugh. If something was funny, sh edidn’t laugh. But if some thing bad happened, she did. When somebody died, for example. Then she suddenly started laughing and laughing really loudly, and couldn’t stop

LENKA: I loooove when skin has that musty river smell.

CHRISTA: And the smell of a cellar. I know.

LENKA: I looove the smell of cellar. I’m addicted to it.

NELLY: And nail polish.

LENKA: Yeah, ..but not quite as much ascellar smella

I remember I got a diary for my 15th birthday. I never knew what to write in it, as if my thoughts somehow weren’t worthy. Whenever I tried to write, I thought that someone would find it and read it after my death, and what a shock that would be for my mom. But if she finds it after my death without me having written a single word, she might think that I didn’t like her gift, or that I was ungrateful or something. So I started writing down the opposite of what I was thinking, sentences that would make my mom happy when I was gone.

- Inwards

By the Platonic books I was admonished to return into myself.18 With you as my guide I entered into my innermost citadel, and was given power to do so because you had become my helper (Ps. 29: 11). I entered and with my soul’s eye, such as it was, saw above that same eye of my soul the immutable light higher than my mind—not the light of every day, obvious to anyone, nor a larger version of the same kind which would, as it were, have given out a much brighter light and filled everything with its magnitude.19 It was not that light, but a different thing, utterly different from all our kinds of light. It transcended my mind, not in the way that oil floats on water, nor as heaven is above earth. It was superior because it made me, and I was inferior because I was made by it. The person who knows the truth knows it, and he who knows it knows eternity. Love knows it.20 Eternal truth and true love and beloved eternity: you are my God. To you I sigh ‘day and night’ (Ps. 42: 2). When I first came to know you, you raised me up to make me see that what I saw is Being, and that I who saw am not yet Being. And you gave a shock to the weakness of my sight by the strong radiance of your rays, and I trembled with love and awe.21’ And I found myself far from you ‘in the region of dissimilarity’, 22 and heard as it were your voice from on high: ‘I am the food of the fully grown; grow and you will feed on me. And you will not change me into you like the food your flesh eats, but you will be changed into me.’ […] I heard in the way one hears within the heart, and all doubt left me.23’ I would have found it easier to doubt whether I was myself alive than that there is no truth ‘understood from the things that are made’ (Rom. 1: 20).

~ Confession, VII (16)

- Brazil (1985)

Spoilers ahead. I wrote while watching, so this is very stream-of-consciousness. Take care.

The actress is very cute, but holy this is so undeserved. Our protagonist destroys her whole life and she falls for him??? Also, suits with a hat and a long mantle are such a vibe. The movie looks gorgeous, I love its surreal aspects. It works a lot with perspective tricks, which is cool.

I wonder what this is about, a myth? Maybe a Jungian archetype? Something something, birth of tragedy? This guy’s undeserved lover, undeserved that he got saved, like how many people died to save him and why? He’s not even important. Is the ending meant to be him as some kind of Christ figure taking the debt of everyone onto himself?

Maybe it was a kind of dream all along, like the terrorist being some kind of multiple-personality disorder? Also why does this meme keep happening every 30 minutes where the FBI raids this one guy’s house? Anybody know what meme I’m talking about?

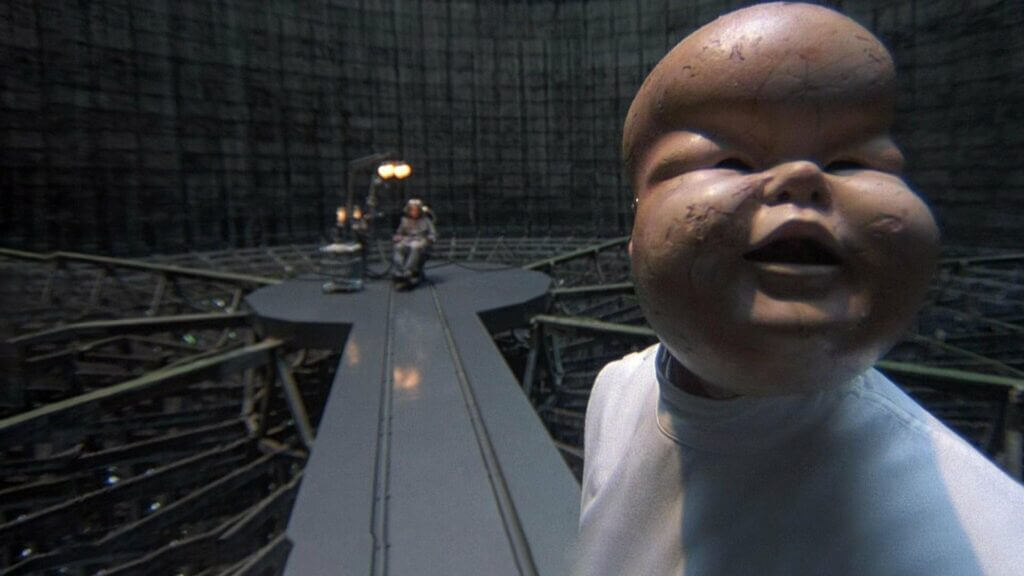

Maybe it’s a psychological thriller, like it’s all in his mind like the movie Boes is afraid? Also, am I the only one who thinks it has Dark Souls elements, with the huge samurai and the little guys with baby masks, holding chains in their hands? What is this ending?????

Oh, okay. It’s a tragedy. That makes it a lot better than the apparently happy ending where they drive off with their truck into nature. 7/10

Edit: I feel like the movie lends itself very much to a Nietzschean lens of interpretation. Maybe I’ll formalize this someday in more detail, but rapid-fire, some themes: Sam’s dream life as a slave-revolt of the imaginary; Jill as alter/inversion/value-transvaluation; bureaucracy as late-modern Apollo; ressentiment; Brazil’s bureaucracy as a Nietzschean “decadent culture.”

Brazil When hearts were entertained in June We stood beneath an amber moon And softly whispered ‘some day soon’

We kissed and clung together Then Tomorrow was another day The morning found me miles away With still a million things to say

Now When twilight beams the skies above Recalling thrills of our love There’s one thing I’m certain of

Return I will To old Brazil

I2P

I2P