- Systemize Art

- Dog Playing in the Snow

- Alien vs Monster (2009)

The avengers of Pixar or something. 6/10

Monsters, I’m so proud of you, I could cry, if I hadn’t lost my tear ducts in the war. But not cryin’ will have to wait. The world needs you again.

- The Two Popes (2019)

Not as good as the other pope movie (Conclave), but decent. 6.5/10

- 2025

Like last year a short reflection on this year.

Media

I included only media that I haven’t mentioned elsewhere already.

- I read 32 proper books; the best one was Why Buddhism Is True.

- Movies of the year: Angles Egg (1985), Sirāt (2025), Ichi the Killer (2001) and Lilya 4 Ever (2002).

- Song of the year: Bloodline by awakebutstillinbed.

- Album of the year: what people call low self-esteem is really just seeing yourself the way other people see you and Windswept Adan.

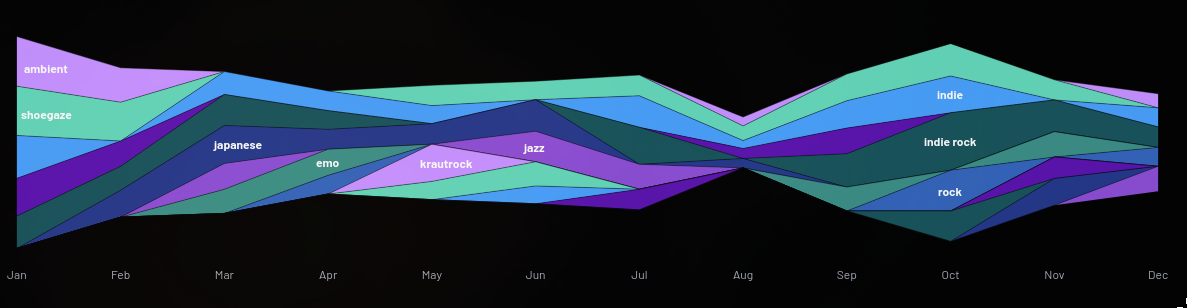

My top music tags/genre of 2025, that I listened to. Website

- I wrote 16 articles.

- I wrote 66 paper summaries.

- I wrote approximately 228,483 words in total.

- The total storage needed for the website has increased to 3.7 GB.

Other

- Started writing my bachelor thesis.

- Started writing a scientific paper (hopefully it gets published).

I2P

I2P